Proceedings of 23rd International Business Research Conference

advertisement

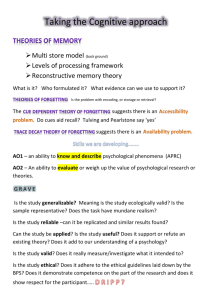

Proceedings of 23rd International Business Research Conference 18 - 20 November, 2013, Marriott Hotel, Melbourne, Australia, ISBN: 978-1-922069-36-8 Effects of Psychological Contract Breach, Ethical Leadership and Supervisors’ Fairness on Employees’ Performance and Wellbeing Ezaz Ahmed and Michael Muchiri The aim of this conceptual paper is to propose pathways through which psychological contract breach, ethical leader behaviour, and supervisors’ fairness are related to employees’ attitudes, behaviours and wellbeing. The paper reviews extant literature and builds a logical framework depicting the interrelationships among psychological contract breach, ethical leader behaviours, and supervisors’ fairness, and how they are related to employees’ attitudes, behaviour and wellbeing. Initially, we propose a direct effect of psychological contract breach on job satisfaction, job neglect, organisational citizenship behaviour, intention to leave and employee wellbeing. We also propose that ethical leadership behaviour and supervisors’ fairness will moderate the relationship between psychological contract breach and employees’ attitudes, behaviour and wellbeing. Based on the proposed conceptual framework, the paper proposes several testable research propositions. Finally, the paper outlines steps to advance organisational theory in regard to the effects of psychological contract breach, ethical leader behaviour and supervisors’ fairness on employee outcomes. Field: Human resources management, organisational behaviour, managing people and organisation. 1. Introduction There is an emerging literature in organisational theory which recognises the importance of employees‟ psychological contracts (Middlemiss, 2011; Rousseau, 1989) and how psychological contract breach (PCB) would have significant consequences at the individual, group, and organisational levels. Indeed, recent studies suggest that psychological contract breach is related to job satisfaction, job neglect, organisational citizenship behaviours, intention to leave and employee wellbeing (Conway & Briner, 2005; Middlemiss, 2011). Another stream of research has focused on ethical leadership behaviour, and how it enhances employee attitudes, behaviour and wellbeing (Brown, Trevino, & Harrison, 2005). Specifically, the past research has linked ethical leadership to a variety of individual, team and organisational outcomes (e.g., Avey, Palanski, & Walumbwa, 2010; Brown et al., 2005; Mayer, Kuenzi, Greenbaum, Bardes, & Salvador, 2009; Walumbwa & Schaubroeck, 2009; Walumbwa, Mayer, Wang, Wang,Workman & Christensen, 2011; Walumbwa, Morrison & Christensen, 2012). Related to this discussion, several studies indicate that leadership behaviour, especially supervisor‟s fair treatment of employees significantly influences employees‟ self-conceptions, and employees‟ performance and also employee wellbeing (Gerstner & Day, 1997; Sparr & Sonnentag, Dr Ezaz Ahmed, School of Business and Law, Central Queensland University, Australia. Email: e.ahmed@cqu.edu.au Dr Michael Muchiri, School of Business and Law, Central Queensland University, Australia. Email: m.muchiri@cqu.edu.au 1 Proceedings of 23rd International Business Research Conference 18 - 20 November, 2013, Marriott Hotel, Melbourne, Australia, ISBN: 978-1-922069-36-8 2008; van Dierendonck, Haynes, Borrill, & Stride, 2004; van Knippenberg, van Knippenberg, De Cremer, & Hogg, 2004). Sparr and Sonnentag (2008) found that employees‟ perceived fairness of feedback was positively related to job satisfaction and feelings of control at work and negatively related to job depression and turnover intentions. We propose a conceptual model that fills two significant gaps in the literature. First, employees‟ wellbeing has not been researched systematically as a resultant outcome of employees‟ psychological contract breach. Employees‟ wellbeing will be examined as outcome variable in the proposed model and will contribute to the psychological contract breach, leadership and employee wellbeing literature. Second, organisational researchers have called for research on factors, which moderate the relationship between psychological contract breach and behavioural, attitudinal outcomes and employee wellbeing (Kickul & Lester, 2001; Morrison & Robinson, 1997; Rousseau, 1995; Suazo, Turnley, & Mai-Dalton, 2005; Suazo, Turnley, & Mai-Dalton, 2008). By proposing ethical leadership behaviour and supervisors‟ fairness as moderators between psychological contract breach and employees‟ wellbeing, behavioural and attitudinal outcomes, the proposed conceptual model contributes significantly to the extant literature. Therefore, our conceptual paper has three main objectives. First, in a bid to explain some of the psychological mechanisms through which ethical leader behaviour and perception of supervisor fairness affect employee outcomes, we integrate the extant literature on ethical leader behaviour, supervisor fairness, psychological contract breach, job satisfaction, job neglect, citizenship behaviours, turnover intentions and employee well-being. Second, based on the literature review, we build a conceptual framework useful in explaining the linkages between psychological contract breach, ethical leader behaviour, supervisor fairness, job satisfaction, job neglect, citizenship behaviour, turnover intentions and employee well-being. Finally, the paper outlines steps to advance organisational theory in the field of ethical leader behaviour, supervisor fairness, psychological contract breach and employee outcomes. In the next section we propose a conceptual model (Figure 1) which explicates the interrelationships among the proposed variables. Later, based on the model below and literature review, we put forward propositions explaining possible linkages among psychological contract breach, ethical leader behaviour, supervisor fairness, job satisfaction, job neglect, citizenship behaviour, turnover intentions and employee wellbeing. 2 Proceedings of 23rd International Business Research Conference 18 - 20 November, 2013, Marriott Hotel, Melbourne, Australia, ISBN: 978-1-922069-36-8 Figure 1: Conceptual Model of Psychological Contract Breach and Leader Ethical Behaviour Moderator: Supervisor‟s Fairness (-) (+) Psychological Contract Breach (-) Moderator: Leader Ethical Behaviour (+) (-) Job Satisfaction Job Neglect Organizational Citizenship Behaviour Intention to Leave Employee Wellbeing 2. Literature Review 2.1 Effects of Psychological Contract Breach on Employee Attitudes, Behaviours and Wellbeing Psychological contract is the employee‟s beliefs about explicit and implicit promises made to them in return of their time and effort towards the organizations (Rousseau, 1995). Psychological contract breach refers to an employee‟s cognitive perception that she or he has not received everything that was promised formally or informally by the organization (Morrison & Robinson, 1997). In the last two decades, organizational researchers have increasingly become interested in psychological contracts, mainly due to its negative impact on employees and on organization (Conway & Briner, 2005; Middlemiss, 2011). Psychological contract breach is related to a range of undesirable employee attitudes and behaviours. For example, psychological contract breach is negatively related to: employee‟s trust in management (Zhao, Wayne, Glibkowski, & Bravo, 2007), job satisfaction (Raja, Johns, & Ntalianis, 2004; Zhao et al., 2007), intentions to remain with the organization (Suazo et al., 2005; Turnley & Feldman, 1998, 1999, 2000), employee performances (Johnson & O'Leary-Kelly, 2003), citizenship behaviour (Restubog, Bordia, & Tang, 2007; Suazo & Stone-Romero, 2011; Suazo et al., 2005), civic virtue behaviour (Chambel & Alcover, 2011) and employee commitment (Lester, Turnley, Bloodgood & Bolino, 2002; Zhao et al., 2007) and positively related to workplace deviant behaviour (Bordia, Restubog, & Tang, 2008), employees‟ neglect of job duties (Turnley & Feldman, 1998, 1999, 2000), job burnout (Chambel & Oliveira-Cruz, 2010), employee‟s cynicism about their employer (Johnson & O'Leary-Kelly, 2003), higher absenteeism (Johnson & O'Leary-Kelly, 2003) and revenge cognitions (Ahmed, Bordia, & Restubog, 2007; Bordia et al., 2008). 3 Proceedings of 23rd International Business Research Conference 18 - 20 November, 2013, Marriott Hotel, Melbourne, Australia, ISBN: 978-1-922069-36-8 2.1.1 Job Satisfaction Job satisfaction is considered one of the most important work attitudes and has been linked across numerous studies to psychological contract breach (Zhao et al., 2007). The primary work attitudes of job satisfaction, organizational commitment, and turnover intentions have shown robust links to psychological contract violation (de Jong, Schalk, & De Cuyper, 2009; Zhao et al., 2007). In particular, meta-analytic evidence from 28 studies suggests that there is a strong negative relationship between job satisfaction and psychological contract breech (Zhao et al., 2007). Here the construct of job satisfaction is considered to reflect a reasoned evaluation of an individual‟s job situation, where there is a comparison between desired and actual benefits that positively affect the satisfaction of important needs (Blomme, Van Rheede, & Tromp, 2009). Therefore, in our research we chose to examine job satisfaction as an outcome variable associated with psychological contract breach. It is thus predicted that: Proposition 1a: Employees’ psychological contract breach will be negatively related to employees’ job satisfaction. 2.1.2 Job Neglect Earlier studies have suggested that psychological contract breach negatively influences employees‟ attitudes towards their organizations and in role and extra role job behaviour (Lester et al., 2002; Robinson, 1996; Robinson & Rousseau, 1994). Organizational researchers have suggested that a breach of employees‟ psychological contract negatively impact on their in-role job performances (Johnson & O'Leary-Kelly, 2003; Restubog et al., 2007; Suazo, 2009; Suazo et al., 2005; Turnley, Bolino, Lester & Bloodgood, 2003). After a psychological contract breach, employees may withdraw their in-role performance voluntarily as they perceive that the organization did not fulfil its obligations or the organization may not fulfil the promises in future. Examples of employee neglect at work include a half-hearted effort to complete a task, completing tasks to low standards, higher absenteeism from the workplace, not attending office or business meetings and not maintaining office hours. Based on an empirical study with 804 managers, Turnley and Feldman (1998) suggested that employees perceiving a psychological contract breach reduce their in-role job performances. In a study with Chinese sample, Chen and colleagues have reported that employees‟ perceived psychological contract breach was negatively related to their work performances (Chen, Tsui, & Zhong, 2008). Employees‟ withdrawal of contribution to the organization after a psychological contract breach can be explained with social exchange theory (Blau, 1964). According to social exchange theory (Blau, 1964), employees are motivated to maintain a fair and balanced exchange relationship with their organizations. In the event of a psychological contract breach, employees may believe their organization cannot be trusted to fulfil its obligations and does not care about employee well-being (Rousseau, 1995). Thus, the employees will be motivated to restore balance to the employment relations in some ways. One way to restore balance in the employment relationship would be by reducing employee‟s contribution to the organization. As such, employees reduce their in-role job efforts to balance this relationship (Chen et al., 2008; Lester et al., 2002; Suazo et al., 2005). Thus, it is expected that psychological contract breach will be positively related to neglect of job performance. Thus, it is proposed that: 4 Proceedings of 23rd International Business Research Conference 18 - 20 November, 2013, Marriott Hotel, Melbourne, Australia, ISBN: 978-1-922069-36-8 Proposition 1b: Employees’ psychological contract breach will be positively related to employees’ job neglect. 2.1.3 Organisational Citizenship Behaviour (OCB) OCB can be referred to as a set of discretionary workplace behaviours that exceed one‟s basic job requirements. OCB can be termed as extra role behaviours that promote organisational effectiveness (Organ, 1988; Robinson & Morrison, 1995). The importance of OCB in effective organisational functioning is well documented (Podsakoff, Whiting, Podsakoff & Blume, 2009; Podsakoff, MacKenzie, Paine & Bachrach, 2000; Organ & Paine, 2001). These behaviours encourage cooperation and association among employees in the workplace and enhance the overall productivity, social environment, stability and managerial productivity of the organisation (Podsakoff et al., 2009; Podsakoff et al., 2000). Individuals are believed to engage in OCBs to pay back or reward their organisations for equitable treatment (Robinson & Morrison, 1995; Organ, 1997). Consequently, OCBs are withheld when employers do not provide adequate outcomes (Robinson & Morrison, 1995) as a consequence of unethical leader behaviour (Zellers, Tepper & Duffy, 2002). Thus, it is predicted that: Proposition 1c: Employees’ psychological contract breach will be negatively related to employees’ citizenship behaviours. 2.1.4 Intention to Leave the Organisation After experiencing a negative experience at the workplace (a psychological contract breach), employees may evaluate the situation and question whether to remain in the employment relationship (Turnley & Feldman, 1999).Research on employee turnover has found that intention to leave the organization is a reliable predictor of future turnover (Roehling, 1997). Employees‟ turnover intentions have been a major interest in the management literature. It is likely that if they perceive injustice in the relationship after an abusive supervision and perceive future mistreatment of the same kind, it is likely that they will look for employment elsewhere. This can also be explained from the social exchange perspective. In the event of a psychological contract breach, an employee‟s trust in the fulfilment of future exchanges is severely damaged and the negative treatment denies valued benefits. As a result, they may believe that it is important to look for alternative employment opportunities in order to obtain valued benefits in the future. The actual turnover of employees after a psychological contract breach may impact on organizational performances. Employee turnover is costly to the organisation (Roehling, 1997). From the organisation‟s perspective, it takes substantial time, money and effort to recruit new employees and such loss often disrupts the regular business operations as well as fosters low workforce morale (Kacmar, Andrews, Van Rooy, Steilberg & Cerrone, 2006; Zhao et al., 2007). Actual turnover of employees can be viewed as a tangible impact of a psychological contract breach on the organization. Thus, it is proposed that: Proposition 1d: Employees’ psychological contract breach will be positively related to employees’ intention to leave the organisation. 5 Proceedings of 23rd International Business Research Conference 18 - 20 November, 2013, Marriott Hotel, Melbourne, Australia, ISBN: 978-1-922069-36-8 2.1.5 Employee Wellbeing There is a growing interest among organisational researchers in health, safety, and workplace health promotion as most individuals spend at least a quarter to a third of their time of a day at workplace (Harter, Schmidt & Keyes 2003; Gurt & Elke 2009). Consequently many organisations are integrating a variety of novel practices to cultivate healthy worksites (Grawitch, Gottschalk & Munz 2006). Further, organisations now recognise that healthy workplaces maximise the integration of worker goals for well-being and company objectives for profitability and productivity (Sauter, Lim & Murphy 1996). It is further envisaged that workplace practices and managerial styles do influence employee well-being and organisational effectiveness. Many organisations now realise that you cannot separate out employee health and well-being from clients/customers satisfaction. Grawitch et al. (2006) propose a direct and indirect link between healthy workplace practices and organisational improvements. They categorise healthy workplace practices into five general categories: work-life balance, employee growth and development, health and safety, recognition, and employee involvement. Employee health presupposes a state of complete physical, mental and social well-being (Gurt & Elke 2009, p.29), and is an important factor if organisations are to achieve their set goals. Stressful workplaces have organisational costs and negative consequences for employees. Furthermore, there is evidence showing that other people at work, especially one‟s supervisor, can dramatically affect the way one feels about one‟s work and about oneself (Dellve, Skagert & Vilhelmsson 2007; Gurt & Elke 2009; van Dierendonck et al., 2004). It is argued in the current paper that employees‟ psychological contract breach will influence employee wellbeing and hence it is predicted that: Proposition 1e: Employees’ psychological contract breach will be negatively related to employees’ wellbeing. 2.2 Moderating Effects of Ethical Leader Behaviour Ethical leadership (Brown et al., 2005) has become a rapidly expanding area of enquiry. Ethical leadership is defined as „„the demonstration of normatively appropriate conduct through personal actions and interpersonal relationships, and the promotion of such conduct to followers through two-way communication, reinforcement, and decisionmaking‟‟ (Brown et al., 2005, p. 120). Ethical leadership portrays a leader‟s traits, behaviours and practices of ethical conduct in the organisational context (Brown et al., 2005). Organisational researchers have suggested that ethical leadership is positively related to pro-social behaviour and negatively related to deviant behaviours (e.g., Avey et al., 2010; Brown et al., 2005; Mayer et al., 2009; Walumbwa & Schaubroeck, 2009). There is a scope of investigating ethical leader behaviour in relationship between psychological contract breach and employee outcomes. As psychological contract is perceptual, subjective and idiosyncratic in nature, trust and fairness are vital in strengthening the relationship. The strength of the employees‟ emotional and behavioural responses after a psychological contract breach can be moderated by the employees‟ cognitive assessments of the situation within which the breach took place (Kickul, Lester, & Finkl, 2002, Morrison and Robinson, 1997, Rousseau, 1995). Further, recent studies have also confirmed that ethical leader behaviour is positively related to employee performances (Walumbwa et al., 2011, 2012). 6 Proceedings of 23rd International Business Research Conference 18 - 20 November, 2013, Marriott Hotel, Melbourne, Australia, ISBN: 978-1-922069-36-8 Empirical research suggests that citizenship behaviours may be withdrawn by an employee in response to the negative treatment received (Zellers et al., 2002). There is no doubt that employees perceive unethical leader behaviour as a negative and unwanted situation. Unethical leader behaviour indicates an imbalance in the social exchange relationship, similar to distributive injustice (Zellers et al., 2002). In order to “get even” with the organization after an unethical leader behaviour, employees are likely to reduce their commitments to the organization and contribute less in the form of citizenship behaviours (Zellers et al., 2002). The moderating effects of leader ethical behaviour are proposed between employees‟ psychological contract breach and resultant outcomes. Proposition 2a: Leader ethical behaviour will moderate the relationship between psychological contract breach and employee’s job satisfaction such that the relationship between psychological contract breach and employee’s job satisfaction will be stronger when leader ethical behaviour is high than when it is low. Proposition 2b: Leader ethical behaviour will moderate the relationship between psychological contract breach and employee’s job neglect such that the relationship between psychological contract breach and employee’s job neglect will be stronger when leader ethical behaviour is high than when it is low. Proposition 2c: Leader ethical behaviour will moderate the relationship between psychological contract breach and employee’s organisational citizenship behaviours such that the relationship between psychological contract breach and employee’s organisational citizenship behaviours will be stronger when leader ethical behaviour is high than when it is low. Proposition 2d: Leader ethical behaviour will moderate the relationship between psychological contract breach and employee’s intention to leave such that the relationship between psychological contract breach and employee’s intention to leave will be stronger when leader ethical behaviour is high than when it is low. Proposition 2e: Leader ethical behaviour will moderate the relationship between psychological contract breach and employee wellbeing such that the relationship between psychological contract breach and employee wellbeing will be stronger when leader ethical behaviour is high than when it is low. 2.3 Moderating Effects of Supervisor Fairness Supervisor fairness refers to the employees‟ perceptions of fairness in the workplace in terms of how they are treated (interactional justice) (Greenberg, 1990, Lee and Allen, 2002). Supervisor fairness is synonymous to interactional justice. Prior justice literature has revealed that employee‟s perception of justice can impact on their job performances (Lind and Tyler, 1988), workplace deviant behaviours (Aquino, Lewis & Bradfield, 1999, Greenberg, 1993) and citizenship behaviours (Moorman, 1991). Employee‟s perception of the supervisor fairness can also be influential in forming their attitudes and behaviour (Bies and Moag, 1986). Supervisor fairness is positively related to job commitment and citizenship behaviours (Coyle-Shapiro, 2002). Hence, Fairness perceptions at work influence employees‟ attitudes and behaviours in organizations (Blader & Tyler, 2005). 7 Proceedings of 23rd International Business Research Conference 18 - 20 November, 2013, Marriott Hotel, Melbourne, Australia, ISBN: 978-1-922069-36-8 Employees care about being treated fairly, because fairness serves psychological needs, including „„control, belonging, self-esteem and meaningful existence‟‟ (Cropanzano, Byrne, Bobocel, & Rupp, 2001, p. 175). As suggested by Sparr and Sonnentag (2008), fairness of specific leadership behaviours (i.e. feedback delivery towards work-related outcomes) are likely to enhance our understanding of which leadership behaviours are important to employees and how they can be improved. There are relatively few studies that have explored the moderating role of supervisor fairness in the relationship between psychological contract breach and employee outcomes. In a longitudinal study of 147 managers, Robinson and Morrison (2000) found that perception of fairness and attribution moderated the relationship between psychological contract breach and feelings of violation. Skarlicki and Folger (1997) have revealed that high levels of supervisor fairness can moderate employee‟s retaliatory behaviours. Thus, justice perceptions may play a critical role in shaping employee‟s cognitive assessment of psychological contract breach and consequently moderate employee attitudes and behaviours. Specifically, the resultant employees‟ attitudes and behaviour after a psychological contract breach can largely depend on high or low levels of supervisor fairness. Based on the above discussion, it can be argued that employees‟ perception of supervisor fairness can influence employees‟ attitudinal, behavioural outcomes and wellbeing. Hence, it is suggested that: Proposition 3a: Perception of supervisor’s fairness will moderate the relationship between psychological contract breach and employee’s job satisfaction such that the relationship between psychological contract breach and employee’s job satisfaction will be stronger when perception of supervisor’s fairness is high than when it is low. Proposition 3b: Perception of supervisor’s fairness will moderate the relationship between psychological contract breach and employee’s job neglect such that the relationship between psychological contract breach and employee’s job neglect will be stronger when perception of supervisor’s fairness is high than when it is low. Proposition 3c: Perception of supervisor’s fairness will moderate the relationship between psychological contract breach and employee’s organisational citizenship behaviours such that the relationship between psychological contract breach and employee’s organisational citizenship behaviours will be stronger when perception of supervisor’s fairness is high than when it is low. Proposition 3d: Perception of supervisor’s fairness will moderate the relationship between psychological contract breach and employee’s intention to leave such that the relationship between psychological contract breach and employee’s intention to leave will be stronger when perception of supervisor’s fairness is high than when it is low. Proposition 3e: Perception of supervisor’s fairness will moderate the relationship between psychological contract breach and employee wellbeing such that the relationship between psychological contract breach and employee wellbeing will be stronger when perception of supervisor’s fairness is high than when it is low. 8 Proceedings of 23rd International Business Research Conference 18 - 20 November, 2013, Marriott Hotel, Melbourne, Australia, ISBN: 978-1-922069-36-8 3. Conclusion The objective of the paper was to integrate and propose the relationships among employees‟ psychological contract breach, ethical leader behaviour, supervisor fairness and employee attitudes, behaviour and wellbeing. Based on the extant literature, it is argued that employees‟ psychological contract breach, managers‟ ethical behaviour and employee perception of fairness would influence employees‟ attitudes, behaviours and wellbeing. The proposed model highlights the significance of managers‟ use of ethical behaviour and supervisors‟ fairness between the relationship employees‟ psychological contract breach and resultant behavioural, attitudinal outcomes. The model also emphasises on the impact of employee wellbeing after a psychological contract breach. To advance organisational theory on psychological contract breach, ethical leader behaviour, supervisor fairness, job satisfaction, job neglect, citizenship behaviours, turnover intentions and employee wellbeing, this paper proposes several steps. First, future research should consciously integrate ethical leader behaviour and supervisor fairness in comprehensive organisational studies which examine how leadership and managerial behaviour manifest in organisations. Second, researchers should design broader studies which examine the interplay among ethical leader behaviour, supervisor fairness and psychological contract breach, so that we understand how they influence organisational effectiveness in managing employment relationship. We encourage organisational researchers to test out our research model and the accompanying propositions to see if there are significant relationships among the proposed linkages between psychological contract breach, ethical leader behaviour, supervisor fairness, job satisfaction, job neglect, citizenship behaviours, turnover intentions and employee wellbeing. References Ahmed, E, Bordia, P and Restubog, SLD 2007, Revenge seeking and forgiveness: Employees' cognitive responses after a psychological contract breach. Paper presented at the 9th South Asian Management Forum, Dhaka, Bangladesh. Aquino, K, Lewis, MU and Bradfield, M 1999, Justice constructs, negative affectivity, and employee deviance: A proposed model and empirical test. Journal of Organizational Behaviour, Vol. 20, pp. 1073-1091. Avey, JB, Palanski, ME and Walumbwa, FO 2010, When leadership goes unnoticed: The moderating role of follower self-esteem on the relationship between ethical leadership and follower behavior. Journal of Business Ethics, doi:10.1007/s10551010-0610-2. Bies, RJ and Moag, JS 1986, Interactional justice: Communication criteria of fairness. Research on Negotiation in Organizations, Vol. 1, pp. 43-55. Blader, SL and Tyler, TR 2005, How can theories of organizational justice explain the impact of fairness? In J. Greenberg & J. A. Colquitt (Eds.), Handbook of Organizational Justice (pp. 329-354). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. Blau, PM 1964, Exchange and power in social life. New York, NY: Wiley and Sons. 9 Proceedings of 23rd International Business Research Conference 18 - 20 November, 2013, Marriott Hotel, Melbourne, Australia, ISBN: 978-1-922069-36-8 Bordia, P, Restubog, SLD and Tang, RL 2008, When employees strike back: Investigating mediating mechanisms between psychological contract breach and workplace deviance. Journal of Applied Psychology, Vol. 93, No. 5, pp. 1104-1117. Blomme, R, Van Rheede, A and Tromp, D 2009, The hospitality industry: An attractive employer? An exploration of students‟ and industry workers‟ perceptions of hospitality as a career field. Journal of Hospitality & Tourism Education, Vol. 21, No. 2, pp. 6-14. Brown, ME, Trevino, LK and Harrison, DA, 2005, Ethical leadership: a social learning perspective for construct development and testing. Organizational Behaviour and Human Decision Processes, Vol. 97, pp. 117-134. Chambel, MJ and Alcover, CM, 2011, The psychological contract of call-centre workers: Employment conditions, satisfaction and civic virtue behaviours. Economic and Industrial Democracy, Vol. 32, No. 1, pp. 115-134. Chambel, MJ and Oliveira-Cruz, F, 2010, Breach of psychological contract and the development of burnout and engagement: A longitudinal study among soldiers on a peace-keeping mission. Military Psychology, Vol. 22, pp. 110-127. Chen, ZX, Tsui, AS and Zhong, L, 2008, Reactions to psychological contract breach: A dual perspective. Journal of Organizational Behavior, Vol. 29, pp. 527-548. Conway, N and Briner, RB, 2005, Understanding psychological contracts at work: a critical evaluation of theory and research: Oxford University Press, USA. Coyle-Shapiro, J, 2002, A psychological contract perspective on organizational citizenship behavior. Journal of Organizational Behavior, Vol. 23, pp. 927-946. Cropanzano, R, Byrne, ZS, Bobocel, DR and Rupp, DE, 2001, Moral virtues, fairness heuristics, social entities, and other denizens of organizational justice. Journal of Vocational Behavior, Vol. 58, pp. 164-209. Dellve, L, Skagert, K and Vilhelmsson, R, 2007, Leadership in workplace health promotion projects: 1- and 2-year effects on long-term work attendance. European Journal of Public Health, Vol. 17, No. 5, pp. 471-476. de Jong, J, Schalk, R and de Cuyper, N, 2009, Balanced versus unbalanced psychological contracts in temporary and permanent employment: Associations with employee attitudes. Management and Organization Review, Vol. 5, No. 3, pp. 329-351. Gerstner, CR and Day, DV, 1997, Meta-analytic review of leader member exchange theory: Correlates and construct issues. Journal of Applied Psychology, Vol. 82, No. 6, pp. 827-844. Grawitch, MJ, Gottschalk, M and Munz, DC, 2006, The path to a healthy workplace: A critical review linking healthy workplace practices, employee well-being, and organizational improvements. Consulting Psychology Journal, Vol. 58, pp. 129–147. Greenberg, J, 1990, Organizational justice: Yesterday, today, and tomorrow. Journal of Management, Vol. 16, pp. 399-432. Greenberg, J, 1993, The social side of fairness: Interpersonal and informational classes of organizational justice. In R. Cropanzano(Ed.), Justice in the workplace: Approaching Fairness in Human Resource Management, pp. 79-103. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum. Gurt, J and Elke, G, 2009, Health promoting leadership: the mediating role of organisational health culture. Ergonomics and Health Aspects, LNCS 5624, pp. 2938. Harter, JK, Schmidt, FL and Keyes, CLM, 2003, Well-being in the workplace and its relationship to business outcomes: A review of the Gallup studies. Flourishing: 10 Proceedings of 23rd International Business Research Conference 18 - 20 November, 2013, Marriott Hotel, Melbourne, Australia, ISBN: 978-1-922069-36-8 Positive Psychology and the Life Well-Lived. Washington, D.C.: American Psychological Association, pp. 205-224. Johnson, JL and O'Leary-Kelly, AM, 2003, The effects of psychological contract breach and organizational cynicism: not all social exchange violations are created equal. Journal of Organizational Behavior, Vol. 24, No. 5, pp. 627-647. Kacmar, KM, Andrews, MC, Van Rooy, DL, Steilberg, RC and Cerrone, S, 2006, Sure everyone can be replaced but at what cost? Turnover as a predictor of unit-level performance. Academy of Management Journal, Vol. 49, No. 1, pp. 133–144. Kickul, J and Lester, SW, 2001, Broken promises: equity sensitivity as a moderator between psychological contract breach and employee attitudes and behavior. Journal of Business and Psychology, Vol. 16, No. 2, pp. 191-217. Kickul, J, Lester, SW and Finkl, J, 2002, Promise breaking during radical organizational change: do justice interventions make a difference? Journal of Organizational Behavior, Vol. 23, No. 4, pp. 469-488. Lee, K and Allen, NJ, 2002, Organizational citizenship behavior and workplace deviance: the role of affect and cognitions. Journal of Applied Psychology, Vol. 87, pp. 131-42. Lester, SW, Turnley, WH, Bloodgood, JM and Bolino, MC, 2002, Not seeing eye to eye: differences in supervisor and subordinate perceptions of and attributions for psychological contract breach. Journal of Organizational Behavior, Vol. 23, No. 1, pp. 39-56. Lind, EA and Tyler, TR, 1988, The social psychology of procedural justice, Plenum Press, New York. Mayer, DM, Kuenzi, M, Greenbaum, R, Bardes, M and Salvador, R, 2009, How low does ethical leadership flow? Test of a trickle-down model. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, Vol. 108, pp. 1-13. Middlemiss, S, 2011, The psychological contract and implied contractual terms: Synchronous or asynchronomous models? International Journal of Law and Management, Vol. 53, No. 1, pp. 32-50. Moorman, RH, 1991, Relationship between organizational justice and organizational citizenship behaviors: do fairness perceptions influence employee citizenship? Journal of Applied Psychology, Vol. 76, pp. 845-855. Morrison, EW and Robinson, SL, 1997, When employees feel betrayed: A model of how psychological contract violation develops. The Academy of Management Review, Vol. 22, No. 1, pp. 226-256. Organ, DW, 1988, Organisational citizenship behaviour: The good soldier syndrome. Lexington, Massachusetts: Lexington Books. Organ, DW, 1997, Organizational citizenship behavior: It's construct clean-up time. Human Performance, Vol. 10, pp. 85-97. Organ, DW and Paine, JB, 2001, A new kind of performance for industrial and organisational psychology: Recent contributions to the study of organisational citizenship behaviour. In C. Cooper & I. Robertson (Eds.), Organizational psychology and development: A reader for students and practitioners, Vol. 14, pp. 337-368, Chichester, England: John Wiley & Sons Ltd. Podsakoff, PM, MacKenzie, SB, Paine, JB and Bachrach, DG, 2000, Organizational citizenship behaviors: A critical review of the theoretical and empirical literature and suggestions for future research. Journal of Management, Vol. 26, pp. 513-563. 11 Proceedings of 23rd International Business Research Conference 18 - 20 November, 2013, Marriott Hotel, Melbourne, Australia, ISBN: 978-1-922069-36-8 Podsakoff, NP, Whiting, SW, Podsakoff, PM and Blume, BD, 2009, Individual- and organizational-level consequences of organizational citizenship behaviors: A metaanalysis. Journal of Applied Psychology, Vol. 94, pp. 122–141. Raja, U, Johns, G and Ntalianis, F, 2004, The impact of personality on psychological contracts. The Academy of Management Journal, Vol. 47, No. 3, pp. 350-367. Restubog, SLD, Bordia, P and Tang, RL, 2007, Behavioural Outcomes of Psychological Contract Breach in a Non-Western Culture: The Moderating Role of Equity Sensitivity. British Journal of Management, Vol. 18, No. 4, pp. 376-386. Robinson, SL, 1996, Trust and breach of the psychological contract. Administrative Science Quarterly, Vol. 41, No. 4, pp. 574-599. Robinson, SL and Morrison, EW, 1995, Psychological contracts and OCB: The effect of unfulfilled obligations on civic virtue behaviour. Journal of Organizational Behavior, Vol.16, pp. 289–298. Robinson, SL and Morrison, WE, 2000, The development of psychological contract breach and violation: a longitudinal study. Journal of Organizational Behavior, Vol. 21, pp. 525-546. Robinson, SL and Rousseau, DM, 1994, Violating the psychological contract: not the exception but the norm. Journal of Organizational Behavior, Vol. 15, pp. 245-259. Roehling, MV, 1997, The origins and early development of the psychological contract construct. Journal of Management History, Vol. 3, No. 2, pp. 204–217. Rousseau, DM, 1989, Psychological and implied contracts in organizations. Employee Responsibilities and Rights Journal, Vol. 2, pp. 121-139. Rousseau, DM, 1995, Psychological contracts in organizations: Understanding written and unwritten agreements. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. Sauter, SL, Lim, SY and Murphy, LR, 1996, Organizational health: A new paradigm for occupational stress research at NIOSH. Journal of Occupational Mental Health, Vol. 4, No. 4, pp. 248–254. Skarlicki, DP and Folger, R, 1997, Retaliation in the workplace: The roles of distributive, procedural, and interactional justice. Journal of Applied Psychology, Vol. 82, pp. 434443. Sparr, JL and Sonnentag, S, 2008, Fairness perceptions of supervisor feedback, LMX and employee well-being at work. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, Vol. 17, pp. 198-225. Suazo. MM, Turnley, WH and Mai-Dalton, RR, 2005, The role of perceived violation in determining employee's reactions to psychological contract breach. Journal of Leadership and Organizational Studies, Vol. 12, No. 1, pp. 24-36. Suazo, MM, Turnley, WH and Mai-Dalton, RR, 2008, Characteristics of the supervisorsubordinate relationship as predictors of psychological contract breach. Journal of Managerial Issues, Vol. 20, pp. 295-312. Suazo, MM, 2009, The mediating role of psychological contract violation on the relations between psychological contract breach and work-related attitudes and behaviors. Journal of Managerial Psychology, Vol. 24, pp. 136-160. Suazo, MM and Stone-Romero, EF, 2011, Implications of psychological contract breach: A perceived organizational support perspective. Journal of Managerial Psychology, Vol. 26, No. 5, pp. 366-382. Turnley, WH and Feldman, DC, 1998, Psychological contract violations during corporate restructuring. Human Resource Management, Vol. 37, No. 1, pp. 71-83. 12 Proceedings of 23rd International Business Research Conference 18 - 20 November, 2013, Marriott Hotel, Melbourne, Australia, ISBN: 978-1-922069-36-8 Turnley, WH and Feldman, DC, 1999, The impact of psychological contract violations on exit, voice, loyalty and neglect. Human Relations, Vol. 52, pp. 895-922. Turnley, WH and Feldman, DC, 2000, Re-examining the effects of psychological contract violations: Unmet expectations and job dissatisfaction as mediators. Journal of Organizational Behavior, Vol. 21, No. 1, pp. 25-42. Turnley, WH, Bolino, MC, Lester, SW and Bloodgood, JM, 2003, The impact of psychological contract fulfillment on the performance of in-role and organizational citizenship behaviors. Journal of Management, Vol. 29, pp. 187-206. Van Dierendonck, D, Haynes, C, Borril, C and Stride, C, 2004, Leadership behaviour and subordinate well-being. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, Vol. 9, No. 2, pp. 165-175. van Knippenberg, D, van Knippenberg, B, De Cremer, D and Hogg, MA, 2004, Leadership, self, and identity: A review and research agenda. Leadership Quarterly, Vol. 15, pp. 825–856. Walumbwa, FO and Schaubroeck, J, 2009, Leader personality traits and employee voice behavior: Mediating roles of ethical leadership and work group psychological safety. Journal of Applied Psychology, Vol. 94, pp. 1275–1286. Walumbwa, FO, Mayer, DM, Wang, P, Wang, H, Workman, K and Christensen, AL, 2011, Linking ethical leadership to employee performance: The roles of leader-member exchange, self-efficacy, and organizational identification, Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, Vol. 115, No. 2, pp. 204-213. Walumbwa, FO, Morrison, EW and Christensen, AL, 2012, The effect of ethical leadership on group performance: The mediating role of group conscientiousness and group voice. Leadership Quarterly, Vol. 23, pp. 953-964. Zellers, KL, Tepper, BJ and Duffy, MK, 2002, Abusive supervision and subordinates‟ organizational citizenship behavior. Journal of Applied Psychology, Vol. 87, No. 6, pp. 1068-1076. Zhao, HAO, Wayne, SJ, Glibkowski, BC and Bravo, J, 2007, The impact of psychological contract breach on work related outcomes: A meta analysis. Personnel Psychology, Vol. 60, No. 3, pp. 647-680. 13