The Made Whole Doctrine: Unraveling the Insurance Subrogation

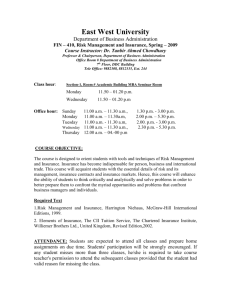

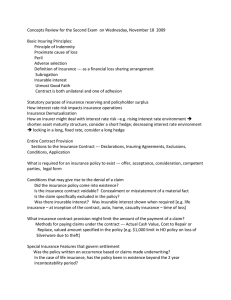

advertisement