SECURED TRANSACTIONS PROBLEM SET 6 Fall Semester 2015 The “Composite Documents” Rule Cases

advertisement

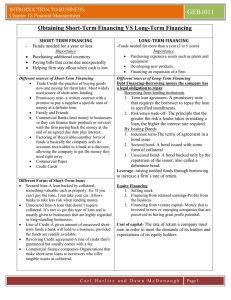

SECURED TRANSACTIONS Fall Semester 2015 PROBLEM SET 6 The “Composite Documents” Rule Cases Understanding the Relationship/Distinction Between Attachment and Perfection In addition to the previous readings for Problem Sets 2 and 5, read §§ 9-322(a) along with In re Laminated Veneers, Inc., 471 F.2d 1124 (2d Cir. 1973), In re Bollinger Corp., 614 F.2d 924 (3d Cir. 1980) and In re Martin Grinding & Machine Works, Inc., 793 F.2d 592 (7th Cir. 1986) (these three cases appear at the end of this problem set). Understanding and evaluating these cases requires you to understand the relationship (and the distinction) between attachment and perfection. It also requires a brief introduction to Article 9's basic priority rule for conflicting security interests. Problem 1 provides this introduction. The remaining problems deal with questions about what constitutes a sufficient “security agreement” for attachment purposes, and the relevance of the contents of the financing statement (if any) to that determination. 1. Two years ago, you applied to borrow $10,000 from First Bank to pay for the out-of-pocket costs of some surgery you needed. First Bank agreed to loan you the money if your credit checked out, and if you would grant a security interest in your wine collection (valued at $40,000). You filled out the loan application, and (with your permission) First Bank filed a financing statement covering the wine collection. A few days later, you received an unexpected bonus at work and no longer needed to borrow the money. Thus, when First Bank called you back to tell you the loan was approved, you advised them you wouldn’t need the loan anymore. Six months ago, you borrowed $25,000 from Boone Bank to pay your child’s school tuition for the year. You signed a security agreement granting Boone Bank a security interest in the wine collection, and Boone Bank filed a financing statement covering the wine collection in the appropriate filing office. Before making the loan, Boone Bank discovered the UCC-1 filing previously made by First Bank and called First Bank for further information; First Bank replied “We never loaned the debtor any money and thus we never took a security interest in the wine collection.” Earlier today, you bought a convertible from Dealer for $40,000 cash, having borrowed that cash from First Bank, which required you to grant a security interest in both the car and the wine collection. You signed a security agreement covering both the car and the wine collection. If you default to both First Bank and Boone Bank, which would have priority in the wine collection and why? 2. Read the Laminated Veneers opinion (which appears on page 3). Laminated Veneers is on the Top 10 list of the worst UCC decisions ever rendered by a judge. The opinion is completely, utterly, totally incorrect. Can you explain why the judge got it wrong? [Hint: The judge focuses on 1 what a potential creditor might inquire about or examine in deciding whether to lend. Based on the result in Problem 1, the judge’s intuition is wrong. Can you see/explain why?] 3. Just before lunch, you get an e-mail from Bubba Charles at Putnam County Bank: Last year, we loaned $10,000 to Alice Holt, who runs a coffee shop, and we took a security interest in her restaurant equipment. She’s now defaulted, and we’re having some trouble with her lawyer. When we demanded that Alice turn over the equipment, her lawyer sent us a reply that says “Putnam County Bank has no valid security interest in the restaurant equipment because there is no authenticated record that satisfies the requirements of an effective security agreement as required by Uniform Commercial Code § 9-203(b)(3) as in effect in this state.” I’ve attached our documentation. Can you call this guy and straighten him out? You open the attachment, and discover that the attachment is a UCC-1 financing statement. It is on the standard UCC-1 form set forth in § 9-521(a). It identifies Alice Holt as the debtor, Putnam County Bank as the secured party, and in the box for the collateral description, there is written the following language: “All of Debtor’s restaurant equipment, presently-owned and after-acquired.” Even though the form does not have a place for a signature, the form was actually signed by Alice Holt, right underneath the collateral description. The form was filed in the UCC filing system in the Secretary of State’s office. You called back Bubba, assuming that the Bank must have had Alice sign a separate security agreement. When you asked him to send it to you, Bubba responded: “There isn’t one. She signed the financing statement. Isn’t that good enough?” Is it? By itself, does the financing statement described above constitute a valid security agreement? Why or why not? 4. Late in the day, you get an e-mail from Dan Arthur at Atlantic Commercial Finance (ACF): Before I was hired at ACF, ACF had extended some unsecured operating capital loans to some businesses that were run by “friends” of ACF’s former president. One of those loans was to a company called Diamond Furniture, Inc. When I took over, they owed ACF $258,000 and were in default. After a bunch of threatening phone calls and a few meetings, we worked out a compromise, and entered into the following letter agreement: ACF (Creditor) and Diamond Furniture, Inc. (Debtor) agree as follows: (1) Debtor acknowledges its debt to Creditor of $258,000. (2) This indebtedness shall be evidenced by an installment note, secured by a lien on all of Diamond Furniture’s accounts receivable, inventory, and equipment, now-existing or after-acquired, which shall be evidenced by a standard form security agreement and shall be perfected by the filing of a financing statement to be filed upon the signing of this letter. (3) When signed by Debtor, this letter will form the basis for Creditor to prepare an 2 installment note and security agreement, and to prepare and file a financing statement. (4) Debtor acknowledges that this agreement is in lieu of Creditor’s filing suit to obtain a judgment against Debtor. I’ve attached a copy of the letter agreement. The president of Diamond Furniture signed the letter. We prepared and filed a financing statement, and we prepared an installment note and security agreement and sent it to Diamond Furniture. I thought it had been signed and returned. Turns out, Diamond Furniture never signed it. I discovered this, to my distress and embarrassment, when we learned today that Diamond Furniture has filed for bankruptcy. Can we use the letter agreement and the financing statement to claim a first priority perfected security interest in the accounts, inventory, and equipment of Diamond Furniture? Or are we screwed because the security agreement we sent them was never signed? Based on your readings in the Understanding book and your reading of the Bollinger (page 4) and Martin Grinding (page 8) cases, what’s your advice to Dan Arthur? What additional information, if any, would you need to advise him fully? 5. Bollinger and Martin Grinding & Machine Works reflect two very different philosophical approaches to dealing with the problem of sloppy documentation by secured parties. Bollinger reflects the view that sloppy documentation does not necessarily defeat attachment if all of the facts and circumstances clearly reflect the parties’ intent to create a security interest in defined collateral. Martin Grinding reflects, by contrast, an approach that appears to punish sloppy documentation as a means to encourage and facilitate “economy and certainty in secured transactions.” [p. 11] Which opinion do you think is more sensible and more defensible as a matter of policy, and why? In re LAMINATED VENEERS CO., INC. United States Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit 471 F.2d 1124 (1973) OAKES, Circuit Judge. Appellant made a secured loan to the bankrupt, Laminated Veneers Co., Inc., which was validly executed on December 20, 1968. The covering security agreement specifically pledged items (including a truck) described in its Schedule A and generally pledged other items through an “omnibus clause” set out in the margin below.1 The omnibus clause gave the appellant a valid secured interest in accounts receivable, inventory, fixtures, machinery, equipment, and tools of the bankrupt. The question here is whether Commercial's secured interest in “equipment” gave it a lien on two Oldsmobile automobiles owned by the bankrupt. We hold that it did not. 1 In addition to all the above enumerated items, it is the intention that this mortgage shall cover all chattels, machinery, equipment, tables, chairs, work benches, factory chairs, stools, shelving, cabinets, power lines, switch boxes, control panels, machine parts, motors, pumps, electrical equipment, measuring and calibrating instruments, office supplies, sundries, office furniture, fixtures, and all other items of equipment and fixtures belonging to the mortgagor, whether herein enumerated or not, now at the plant of Laminated Veneers Co., Inc. located at 115-02 15th Ave. College Point, New York, and all chattels, machinery, fixtures, or equipment that may hereafter be brought in or installed in said premises or any new premises of the mortgagor, to replace, substitute for, or in addition to the above mentioned chattels and equipment with the exception of stock in trade. 3 The appellant relies upon the broad language of New York Uniform Commercial Code § 9-109(2) (McKinney 1964) (hereinafter cited as “U.C.C.”) to show that the “equipment” term of the omnibus clause included the two automobiles. Section 9-109(2) defines “equipment” for present purposes as a residual category which includes all goods not included in the definitions of inventory, farm products or consumer goods. Thus automobiles would fall within this broad category if the definition of Section 9-109 governed for purposes of the security agreement. The classifications of Section 9-109, however, are intended primarily for the purposes of determining which set of filing requirements is proper. We look rather to U.C.C. § 9-110 which requires that the description of personal property “reasonably identif[y]” what is described. The conclusion that greater specificity is required finds additional support in U.C.C. § 9-203(1)(b), which provides that the security agreement must contain a “description” of the collateral. Certainly the word “equipment” does not constitute a “description” of the Oldsmobiles. Unlike a financing statement (U.C.C. § 9-402) which is designed merely to put creditors on notice that further inquiry is prudent, see In re Leichter, 471 F.2d 785 (2d Cir. 1972), the security agreement embodies the intentions of the parties. It is the primary source to which a creditor's or potential creditor's inquiry is directed and must be reasonably specific. See U.C.C. § 9-203, Practice Commentary 1 at 394; P. Coogan, W. Hogan & D. Vagts, Secured Transactions Under the Uniform Commercial Code § 4.06, at 289-90 (Bender's Uniform Commercial Code Service Vol. 1, 1968). What would a potential creditor find upon examination of the security agreement in this case? The only mention of vehicles of any kind in the agreement is the listing of an International truck in Schedule A. Beyond that there is only the “omnibus clause” and the generic “equipment” therein. Any examining creditor would conclude that the truck as the only vehicle mentioned was the only one intended to be covered. We thus need not reach the contention that a prior invalid lien on one of the automobiles inured to the benefit of the trustee for benefit of the estate and as such is superior to the lien of Commercial. For the reasons stated above we affirm the decision of the court below. [The dissenting opinion of LUMBARD, Circuit Judge, is omitted.] In re BOLLINGER CORP. United States Court of Appeals for the Third Circuit 614 F.2d 924 ROSENN, Circuit Judge.... Can a creditor assert a secured claim against the debtor when no formal security agreement was ever signed, but where various documents executed in connection with a loan evince an intent to create a security interest? The district court answered this question in the affirmative and permitted the creditor, Zimmerman & Jansen, to assert a secured claim against the debtor, bankrupt Bollinger Corporation in the amount of $150,000. We affirm.... The facts of this case are not in dispute. Industrial Credit Company (ICC) made a loan to Bollinger Corporation (Bollinger) on January 13, 1972, in the amount of $150,000. As evidence of the loan, Bollinger executed a promissory note in the sum of $150,000 and signed a security agreement with ICC giving it a security interest in certain machinery and equipment. ICC in due course perfected its security interest in the collateral by filing a financing statement.... 4 Bollinger faithfully met its obligations under the note and by December 4, 1974, had repaid $85,000 of the loan leaving $65,000 in unpaid principal. Bollinger, however, required additional capital and on December 5, 1974, entered into a loan agreement with Zimmerman & Jansen, Inc. (Z&J), by which Z&J agreed to lend Bollinger $150,000. Z&J undertook as part of this transaction to pay off the $65,000 still owed to ICC in return for an assignment by ICC to Z&J of the original note and security agreement between Bollinger and ICC. Bollinger executed a promissory note to Z&J, evidencing the agreement containing the following provision: Security. This Promissory Note is secured by security interests in a certain Security Agreement between Bollinger and Industrial Credit Company ... and in a Financing Statement filed by (ICC) ..., and is further secured by security interests in a certain security agreement to be delivered by Bollinger to Z and J with this Promissory Note covering the identical machinery and equipment as identified in the ICC Agreement and with identical schedule attached in the principal amount of Eighty-Five Thousand Dollars. ($85,000). No formal security agreement was ever executed between Bollinger and Z&J. Z&J did, however, in connection with the promissory note, record a new financing statement signed by Bollinger containing a detailed list of the machinery and equipment originally taken as collateral by ICC for its loan to Bollinger.... [Bollinger filed a petition in bankruptcy in March 1975.] Z&J asserted a secured claim against the bankrupt in the amount of $150,000, arguing that although it never signed a security agreement with Bollinger, the parties had intended that a security interest in the sum of $150,000 be created to protect the loan. The trustee in bankruptcy conceded that the assignment to Z&J of ICC’s original security agreement with Bollinger gave Z&J a secured claim in the amount of $65,000, the balance owed by Bollinger to ICC at the time of the assignment. The trustee, however, refused to recognize Z&J’s asserted claim of an additional secured claim of $85,000 because of the absence of a security agreement between Bollinger and Z&J. The bankruptcy court agreed and entered judgment for Z&J in the amount of $55,000, representing a secured claim in the amount of $65,000.... Z&J appealed to the United States District Court for the Western District of Pennsylvania, which reversed the bankruptcy court and entered judgment for Z&J in the full amount of the asserted $150,000 secured claim. The trustee in bankruptcy appeals.... Under Article Nine of the U.C.C., two documents are generally required to create a perfected security interest in a debtor’s collateral. First, there must be a “security agreement” giving the creditor an interest in the collateral. Section 9-203(1)(b) contains minimal requirements for the creation of a security agreement. In order to create a security agreement, there must be: (1) a writing (2) signed by the debtor (3) containing a description of the collateral or the types of collateral. The requirements of section 9-203(1)(b) further two basic policies. First, an evidentiary function is served by requiring a signed security agreement and second, a written agreement also obviates any Statute of Frauds problems with the debtor-creditor relationship. The second document generally required is a “financing statement,” which is a document signed by both parties and filed for public record. The financing statement serves the purpose of giving public notice to other creditors that a security interest is claimed in the debtor’s collateral. Despite the minimal formal requirements set forth in section 9-203 for the creation of a security agreement, the commercial world has frequently neglected to comply with this simple Code provision. Soon after Article Nine’s enactment, creditors who had failed to obtain formal security agreements, but who nevertheless had 5 obtained and filed financing statements, sought to enforce secured claims. Under section 9-402, a security agreement may serve as a financing statement if it is signed by both parties. The question arises whether the converse is true: Can a signed financing statement operate as a security agreement? The earliest case to consider this question was American Card Co. v. H.M.H. Co., 97 R.I. 59, 196 A.2d 150, 152 (1963) which held that a financing statement could not operate as a security agreement because there was no language granting a security interest to a creditor. Although section 9-203(1)(b) makes no mention of such a grant language requirement, the court in American Card thought that implicit in the definition of “security agreement” under section 9-105(1)(h) was such a requirement; some grant language was necessary to “create or provide security.” This view also was adopted by the Tenth Circuit in Shelton v. Erwin, 472 F.2d 1118, 1120 (10th Cir. 1973). Thus, under the holdings of these cases, the creditor’s assertion of a secured claim must fall in the absence of language connoting a grant of a security interest. The Ninth Circuit in In re Amex-Protein Development Corp., 504 F.2d 1056 (9th Cir. 1974), echoed criticism by commentators of the American Card rule. The court wrote: “There is no support in legislative history or grammatical logic for the substitution of the word ‘grant’ for the phrase ‘creates or provides for’.” Id. at 1059-60. It concluded that as long as the financing statement contains a description of the collateral signed by the debtor, the financing statement may serve as the security agreement and the formal requirements of section 9-203(1)(b) are met. The tack pursued by the Ninth Circuit is supported by legal commentary on the issue. See G. Gilmore, Security Interests in Personal Property, § 11.4 at 347-48 (1965). Some courts have declined to follow the Ninth Circuit’s liberal rule allowing the financing statement alone to stand as the security agreement, but have permitted the financing statement, when read in conjunction with other documents executed by the parties, to satisfy the requirements of section 9-203(1)(b). The court in In re Numeric Corp., 485 F.2d 1328 (1st Cir. 1973) held that a financing statement coupled with a board of directors’ resolution revealing an intent to create a security interest were sufficient to act as a security agreement. The court concluded from its reading of the Code that there appears no need to insist upon a separate document entitled “security agreement” as a prerequisite for an otherwise valid security interest. A writing or writings, regardless of label, which adequately describes the collateral, carries the signature of the debtor, and establishes that in fact a security interest was agreed upon, would satisfy both the formal requirements of the statute and the policies behind it. Id. at 1331. The court went on to hold that “although a standard form financing statement by itself cannot be considered a security agreement, an adequate agreement can be found when a financing statement is considered together with other documents.” Id. at 1332. More recently, the Supreme Court of Maine in Casco Bank & Trust Co. v. Cloutier, 398 A.2d 1224, 1231-32 (Me.1979) considered the question of whether composite documents were sufficient to create a security interest within the terms of the Code. Writing for the court, Justice Wernick allowed a financing statement to be joined with a promissory note for purposes of determining whether the note contained an adequate description of the collateral to create a security agreement. The court indicated that the evidentiary and Statute of Frauds policies behind section 9-203(1)(b) were satisfied by reading the note and financing statement together as the security agreement. In the case before us, the district court went a step further and held that the promissory note executed by Bollinger in favor of Z&J, standing alone, was sufficient to act as the security agreement between the parties. In so doing, the court implicitly rejected the American Card rule requiring grant language before a security agreement arises under section 9-203(1)(b). The parties have not referred to any Pennsylvania state cases on 6 the question and our independent research has failed to uncover any. But although we agree that no formal grant of a security interest need exist before a security agreement arises, we do not think that the promissory note standing alone would be sufficient under Pennsylvania law to act as the security agreement. We believe, however, that the promissory note, read in conjunction with the financing statement duly filed and supported, as it is here, by correspondence during the course of the transaction between the parties, would be sufficient under Pennsylvania law to establish a valid security agreement.... We think Pennsylvania courts would accept the logic behind the First and Ninth Circuit rule and reject the American Card rule imposing the requirement of a formal grant of a security interest before a security agreement may exist. When the parties have neglected to sign a separate security agreement, it would appear that the better and more practical view is to look at the transaction as a whole in order to determine if there is a writing, or writings, signed by the debtor describing the collateral which demonstrates an intent to create a security interest in the collateral.2 In connection with Z&J’s loan of $150,000 to Bollinger, the relevant writings to be considered are: (1) the promissory note; (2) the financing statement; (3) a group of letters constituting the course of dealing between the parties. The district court focused solely on the promissory note finding it sufficient to constitute the security agreement. Reference, however, to the language in the note reveals that the note standing alone cannot serve as the security agreement. The note recites that along with the assigned 1972 security agreement between Bollinger and ICC, the Z&J loan is “further secured by security interests in a certain Security Agreement to be delivered by Bollinger to Z&J with this Promissory Note, .... (Emphasis added.) The bankruptcy judge correctly reasoned that ”(t)he intention to create a separate security agreement negates any inference that the debtor intended that the promissory note constitute the security agreement.“ At best, the note is some evidence that a security agreement was contemplated by the parties, but by its own terms, plainly indicates that it is not the security agreement. Looking beyond the promissory note, Z&J did file a financing statement signed by Bollinger containing a detailed list of all the collateral intended to secure the $150,000 loan to Bollinger. The financing statement alone meets the basic section 9-203(1)(b) requirements of a writing, signed by the debtor, describing the collateral. However, the financing statement provides only an inferential basis for concluding that the parties intended a security agreement. There would be little reason to file such a detailed financing statement unless the parties intended to create a security interest.3 The intention of the parties to create a security interest may be gleaned from the expression of future intent to create one in the promissory note and the intention of the parties as expressed in letters constituting their course of dealing. The promissory note was executed by Bollinger in favor of Z&J in December 1974. Prior to the consummation of the loan, Z&J sent a letter to Bollinger on May 30, 1974, indicating that the loan would be made “provided” Bollinger secured the loan by a mortgage on its machinery and equipment. Bollinger sent a letter to Z&J on September 19, 1974, indicating: 2 We do not intend in any way to encourage the commercial community to dispense with signing security agreements as a normal part of establishing a secured transaction. Lawsuits over the existence of a security agreement may be avoided by executing a separate security agreement conforming to the minimal requirements of section 9-203(1)(b). Our decision today only predicts, after our examination of the relevant case law, that Pennsylvania courts would adopt a pragmatic view of the issue raised here and recognize the intention of the parties expressed in the composite documents and not exalt form over substance. 3 Z&J would not have had to file a financing statement for the $65,000 covered by the 1972 security agreement between ICC and Bollinger, inasmuch as the assignee of a security interest is protected by the assignor’s filing. [See § 9-310(c).] 7 With your (Z&J’s) stated desire to obtain security for material and funds advanced, it would appear that the use of the note would answer both our problems. Since the draft forwarded to you offers full collateralization for the funds to be advanced under it and bears normal interest during its term, it should offer you maximum security. Subsequent to the execution of the promissory note, Bollinger sent to Z&J a list of the equipment and machinery intended as collateral under the security agreement which was to be, but never was, delivered to Z&J. In November 1975, the parties exchanged letters clarifying whether Bollinger could substitute or replace equipment in the ordinary course of business without Z&J’s consent. Such a clarification would not have been necessary had a security interest not been intended by the parties. Finally, a letter of November 18, 1975, from Bollinger to Z&J indicated that “any attempted impairment of the collateral would constitute an event of default.” From the course of dealing between Z&J and Bollinger, we conclude there is sufficient evidence that the parties intended a security agreement to be created separate from the assigned ICC agreement with Bollinger. All the evidence points towards the intended creation of such an agreement and since the financing statement contains a detailed list of the collateral, signed by Bollinger, we hold that a valid Article Nine security agreement existed under Pennsylvania law between the parties which secured Z&J in the full amount of the loan to Bollinger.... The minimal formal requirements of section 9-203(1)(b) were met by the financing statement and the promissory note, and the course of dealing between the parties indicated the intent to create a security interest. The judgment of the district court recognizing Z&J’s secured claim in the amount of $150,000 will be affirmed.... In re MARTIN GRINDING & MACHINE WORKS, INC. United States Court of Appeals for the Seventh Circuit 793 F.2d 592 (1986) ESCHBACH, Senior Circuit Judge. The primary issue presented by this appeal is whether, under the Illinois Uniform Commercial Code, loan documents can supplement a security agreement to create a security interest in property inadvertently omitted from the security agreement’s enumeration of secured collateral. The bankruptcy court dismissed a secured party’s claim of a security interest in property not described in the security agreement. The district court affirmed the dismissal. For the reasons stated below, we hold that the loan documents cannot expand the scope of the security agreement and will affirm the district court’s judgment.... In 1977 Martin Grinding & Machine Works, Inc. (“debtor”) received a Small Business Administration (“SBA”) guaranteed loan in the amount of $350,000 from Forest Park National Bank (“Bank”). In return, the debtor executed a security agreement dated October 7, 1977, granting the Bank a security interest in the debtor’s machinery, equipment, furniture, and fixtures. The security agreement, however, inadvertently omitted inventory and accounts receivable from its description of the secured collateral. In addition to the 8 security agreement, the debtor executed other loan documents (collectively referred to as “loan documents”),4 each of which included inventory and accounts receivable as secured property. In 1981 the debtor obtained a second SBA guaranteed loan from the Bank. This loan, in the amount of $233,000, also was secured by the October 7, 1977, security agreement. In 1983 the debtor petitioned for voluntary reorganization under Chapter 11 of the Bankruptcy Code.... The debtor denied that the Bank held a security interest in its inventory and accounts receivable. The Bank filed a complaint in bankruptcy court to determine the extent of the security interest. The bankruptcy court granted the debtor’s motion to dismiss the complaint for failure to state a claim upon which relief could be granted. The district court affirmed in an unpublished opinion. The Bank now appeals.... The Illinois Uniform Commercial Code provides that a security interest is not enforceable against the debtor or third parties with respect to the collateral and does not attach unless (a) the collateral is in the possession of the secured party pursuant to agreement, or the debtor has signed a security agreement which contains a description of the collateral ...; and (b) value has been given; and (c) the debtor has rights in the collateral. Ill.Rev.Stat. ch. 26, ¶ 9-203(1). The parties agree that the debtor has signed a security agreement, that value has been given, and that the debtor has rights in its inventory and accounts receivable. Moreover, they agree that the loan documents provided for a security interest in the debtor’s inventory and accounts receivable, and that the security agreement did not describe inventory and accounts receivable as secured collateral. They, however, differ as to whether the Bank’s security interest extends to collateral beyond that described in the security agreement to include inventory and accounts receivable. The Bank argues that the loan documents must be considered in determining the scope of its security interest. We disagree. Allis-Chalmers Corp. v. Staggs, 117 Ill.App.3d 428, 432, 453 N.E.2d 145, 148 (1983), holds “that a broader description of collateral in a financing statement is ineffective to extend a security interest beyond that stated in the security agreement.” In reaching this result, the court relied upon Ill.Rev.Stat. ch. 26, ¶ 9-201, which provides that a security agreement is effective according to its terms, and upon ¶ 9-203(1)(a), which states that a security interest is not effective against the debtor or third parties unless the debtor has signed a security agreement that contains a description of the collateral. The court reasoned that “a security interest cannot exist in the absence of a security agreement ..., and it follows that a security interest is limited to property described in the security agreement.” It also relied upon the Illinois Code Comment to Ill.Rev.Stat. ch. 26, ¶ 9-110, which states that “ [t]he security agreement and the financing statement are double screens through which the secured party’s rights to collateral are viewed, and his rights are measured by the narrower of the two.” We, therefore, conclude that, under Illinois law, a security interest attaches only to property described in the security agreement. Because the October 7, 1977, security agreement did not include inventory and accounts receivable, the Bank does not hold a security interest in this property. 4 The additional loan documents that described the debtor’s inventory and accounts receivable as secured collateral were: (1) a SBA Authorization and Loan Agreement, dated October 7, 1977; (2) the debtor’s Corporate Resolution, dated October 7, 1977; (3) a Note in the Principal Sum of $350,000, dated October 7, 1977; (4) an Authorization and Loan Agreement, dated February 24, 1981; (5) the debtor’s Corporate Resolution, dated March 10, 1981; and (6) a Note in the Principal Sum of $233,000, dated March 20, 1981. 9 The Bank, however, seeks to distinguish Allis-Chalmers. First, it asserts that Allis-Chalmers involved a dispute between creditors, rather than between a creditor and the debtor’s trustee in bankruptcy. While true, this is a distinction without a difference. The court in Allis-Chalmers decided that a security interest attaches only to collateral described in the security agreement. The Bank’s security agreement did not include inventory and accounts receivable. Therefore, a security interest never attached to the debtor’s inventory and accounts receivable. Because a security interest did not attach to this property under ¶ 9-203(1), the Bank cannot enforce a security interest in inventory and accounts receivable against either a third-party creditor or the debtor. Second, the Bank argues that, although the plaintiff in Allis-Chalmers relied upon only the financing statement to expand the scope of the security interest, the Bank relies not only upon the financing statement, but also upon the other loan documents. Nevertheless, Allis-Chalmers’s holding that a financing statement cannot extend a security interest beyond that stated in the security agreement is only an application of the general rule that parol evidence cannot enlarge an unambiguous security agreement. [Citations omitted.] The October 7, 1977, security agreement is unambiguous on its face: it grants the Bank “a security interest in all machinery, equipment, furniture and fixtures ... now owned and hereafter acquired by Debtor for use in Debtor's business, including without limitation the items described on Schedule ‘A’ attached hereto, together with all replacements thereof and all attachments, accessories and equipment now or hereafter installed therein or attached thereto.” That the security agreement omits any mention of inventory and accounts receivable as secured collateral is unfortunate for the Bank, but does not make the agreement ambiguous. Since the security agreement is unambiguous on its face, neither the financing statement, nor the other loan documents can expand the Bank’s security interest beyond that stated in the security agreement. Furthermore, Palatine National Bank v. Randall (In re Wambach), 484 F.2d 572 (7th Cir.1973), on which the Bank relies, is inapposite. We held in Wambach, 484 F.2d at 575, that parol evidence may show that a transfer purporting to be absolute was in fact for security, and that an assignment of a beneficial interest, absolute on its face, together with other documents relating to the transaction, may constitute a security agreement. Our holding in Wambach that an assignment absolute on its face, other loan documents, and a financing statement may serve as a security agreement in the absence of a document entitled “Security Agreement” in no way suggests that a financing statement and other loan documents might modify an unambiguous security agreement.... Thus, Illinois law provides that a security interest attaches to, and is enforceable against the debtor or a third party with respect to, only property identified by the security agreement as secured collateral. This rule, however, works a result that is contrary to the parties’ intentions when the parties agree that certain property would secure a loan, but the creditor inadvertently omits the property from the security agreement’s enumeration of secured collateral. We, therefore, might inquire what is the rule’s rationale. One answer, which was adopted by Allis-Chalmers, 117 Ill.App.3d at 432, 453 N.E.2d at 843-44, and the district court, is based upon the statutory definition of and requirements for a security agreement. A security agreement is “an agreement which creates or provides for a security interest.” Ill.Rev.Stat. ch. 26, ¶ 9-105(1). The agreement must be reduced to writing and must describe the secured collateral. ¶ 9-203(1)(a). Therefore, if the written security agreement does not provide for a security interest in inventory and accounts receivable, then a security interest in inventory and accounts receivable does not exist. Although dictated by the statutory language, this answer does not consider the rule’s effect upon commercial transactions. 10 Another answer, which was given by the bankruptcy court, is that the rule promotes economy and certainty in secured transactions. The aim of Article 9 is to enable “the immense variety of present-day secured financing transactions ... [to] go forward with less cost and with greater certainty.” Ill.Rev.Stat. ch. 26, ¶ 9-101 Uniform Commercial Code Comment. Accordingly, a purpose of the requisites for a security interest stated in ¶ 9-203 is “evidentiary.” ¶ 9-203 Uniform Commercial Code Comment 3. “The requirement of [a] written record minimizes the possibility of future dispute as to the terms of a security agreement and as to what property stands as collateral for the obligation secured.” Id. The Code contemplates that a subsequent creditor that is considering extending credit to a debtor will examine any financing statements filed under the debtor’s name to determine whether the debtor’s property might be subject to a prior security interest. See J. White & R. Summers, Uniform Commercial Code § 23-3 (2d ed. 1980). If a financing statement gives notice of a prior security interest, then the subsequent creditor can examine the security agreement to determine what property secures the debtor’s existing obligations. The description of the secured collateral contained in the security agreement might be narrower than that in the financing statement.5 Since parol evidence cannot enlarge a security interest beyond that stated by an unambiguous security agreement, then the subsequent creditor can rely upon the face of the security agreement to determine what property is subject to a prior security agreement.6 Since the subsequent creditor, by obtaining a subordination agreement, can guard itself against the risk that its security interest will be subordinated, it should bear the risk of subordination. Unless it undertakes an examination of the underlying loan documents, it, however, cannot protect itself against the risk of a mistake in the construction of an unambiguous prior security agreement. Yet, the prior secured party can easily protect itself against the risk of a mistake in the interpretation of its security agreement simply by comparing the security agreement with the underlying loan documents. Thus, the prior secured party, not the subsequent creditor, should bear the risk of mistakes in the construction of unambiguous security agreements. 5 The discrepancy between the financing statement’s and security agreement’s descriptions of secured collateral might be inadvertent. Either the financing statement might have inadvertently included property that the parties did not intend would serve as secured collateral, or, as happened here, the security agreement might have accidentally omitted property that the parties intended would secure the obligation. The difference might also be intentional. The prior secured party might have filed a broad financing statement before it and the debtor agreed what property would secure the obligation in order to protect the priority of its security interest. See J. White & R. Summers, Uniform Commercial Code § 25-4 (2d ed. 1980). The prior secured party and the debtor might then agree that the obligation would be secured by only some of the property described in the financing statement. Therefore, that the description of secured collateral contained in the security agreement is narrower than that in the financing statement does not necessarily mean that the security agreement inadvertently omitted property that the parties had agreed would secure an obligation. 6 Even when it can determine from the face of an unambiguous security agreement what property is subject to a prior security interest, a cautious subsequent creditor should not simply adopt as secured collateral property that was described in a prior financing statement, but omitted from the prior security agreements. The prior secured party was the first to file a financing statement. Therefore, under Ill.Rev.Stat. ch. 26, ¶ 9-312(5)(a), the priority of any security interest taken by the prior secured party in property described in the financing statement relates back to the date of filing of the financing statement. See J. White & R. Summers, Uniform Commercial Code § 25-4 (2d ed. 1980). Assuming that the subsequent creditor took a security interest in the property that was omitted from the security agreement, the prior secured party could subordinate the subsequent creditor’s security interest by obtaining another security agreement that includes the previously omitted property as secured collateral. See id.; see also 1 G. Gilmore, Security Interests in Personal Property § 15.3 n. 10 (1965). Thus, a careful subsequent creditor would not make a loan that used as security property that was included in a prior financing statement but omitted from the prior security agreement, unless the prior secured party had executed a subordination agreement in favor of the subsequent creditor. See 1 G. Gilmore, supra, § 15.3 n. 10. 11 However, if parol evidence could enlarge an unambiguous security agreement, then a subsequent creditor could not rely upon the face of an unambiguous security agreement to determine whether the property described in the financing statement, but not the security agreement, is subject to a prior security interest. Instead, it would have to consult the underlying loan documents to attempt to ascertain the property in which the prior secured party had taken a security interest. The examination of additional documents, which the admission of parol evidence would require, would increase the cost of, and inject uncertainty as to the scope of prior security interests, into secured transactions. Therefore, although the rule excluding parol evidence works results contrary to the parties’ intentions in particular cases, it reduces the cost and uncertainty of secured transactions generally.7 We, therefore, conclude that the Bank does not hold a security interest in the debtor’s inventory and accounts receivable. The district court thus correctly affirmed the bankruptcy court’s dismissal of the Bank’s claim.... 7 It, however, might be argued that considerations of cost and certainty justify a rule barring parol evidence whenever there is a priority dispute among secured parties, but not when there is a non-priority dispute between a secured party and the debtor. A rule allowing parol evidence to supplement a security agreement with consistent additional terms in only non-priority disputes arguably would permit a subsequent creditor to rely upon an unambiguous security agreement, and also would enable a prior secured party to enlarge the security agreement to include property that the parties had agreed would secure the obligation, but which the written document had inadvertently omitted. Nevertheless, we decline to adopt a rule permitting parol evidence to enlarge an unambiguous security agreement. First, we are aware of no authority that supports such a proposition. Indeed, the holding in Allis-Chalmers, 117 Ill.App.3d at 432, 453 N.E.2d at 843, that “a security interest is limited to property described in the security agreement” would seem to preclude such a rule. Federal courts will not adopt innovative rules of state law without clearer guidance from the state courts. Second, the dispute in this case is not simply between the Bank and the debtor. The debtor has entered bankruptcy and other creditors have submitted claims. To hold that the Bank has a perfected security interest in the debtor’s inventory and accounts receivable might reduce the amount available to satisfy the other creditors’ claims. 12