Proceedings of 8th Annual London Business Research Conference

advertisement

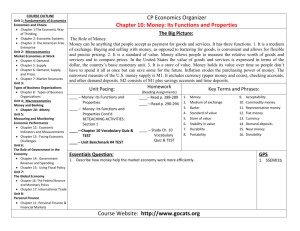

Proceedings of 8th Annual London Business Research Conference Imperial College, London, UK, 8 - 9 July 2013, ISBN: 978-1-922069-28-3 The European Financial Crisis and Institutional Reforms in the Post-Crisis Era: An Unfinished Agenda Uzma Ashraf* The European experience constitutes an interesting precedent and offers a laboratory to observe economic, legal, and political integration experimentation 1 transcending national borders. The lessons learnt by the failure of EU institutions to deal with the global financial crisis as this intensified in Europe and subsequently as it transformed into sovereign debt crisis render it pertinent to analyse the weaker institutional underpinnings in the only single financial market. Theoretically, it is essential for stability of any single financial market to have harmonized set of core rules (not minimum but maximum harmonization – as the European experiment proved it retrospectively) for all of its member states, however, when it comes to EU institutional design, this is one of the major issues. This paper will explore the origins of the European crisis by looking at the basic flaws in the process of monetary integration where economic integration and fiscal solidarity were not given preference over state sovereignty and national fiscal controls. This trade-off was the fundamental flaw in the institutional design of the EU integration structures, particularly in the new initiatives that are being carried out as the result of recent crisis. Therefore, apart from highlighting these flaws, the objective of this research is to expose gaps in the post-crisis regulatory and institutional reforms. I. Introduction Crises episodes almost always lead to new reforms. The quantum of reforms however, corresponds to the magnitude and intensity of the losses incurred by various market players in consequence to that crisis episode. In the post Bretton Woods era - with exception of a few developed economies – crises mostly remained limited to the developing countries only, comparatively, the industrialized economies in the same era remained safer but until 2008, after which the crisis necessitated a need to fundamentally restructure the global financial architecture that has always been determined by the advanced western economies. Eichengreen writes on the 2008 crisis: ―It was for the world what the Asian crisis of 1997-98 had been for the emerging markets: a profoundly alarming wake-up call. By laying bare the fragility of the global markets, it raised troubling questions about the operation of the 21st century world economy. It cast doubts on the efficacy of the light-touch financial regulation and, more generally, on the prevailing commitment to economic and financial liberalization. It challenged the managerial capacity of institutions of global governance. It argued a changing of the guard, pointing to the possibility that the * Uzma Ashraf, PhD candidate at Asian Institute of International Financial Law (AIIFL), University of Hong Kong. Email: oozeeash@hku.hk 1 Wouters, J., & Ramopoulos, T. (2012). The G20 and Global Economic Governance: Lessons from Multilevel European Governance? Journal of International Economic Law. doi: 10.1093/jiel/jgs036 1 Proceedings of 8th Annual London Business Research Conference Imperial College, London, UK, 8 - 9 July 2013, ISBN: 978-1-922069-28-3 economies that had been leaders in the global growth stakes in the past would no longer be leaders in the future‖.2 The crisis in 2008, as it is said, ‗a once-in-a-century event‘, has exposed various dimensions of the regulatory ambit. The sovereign debt crisis that followed the general global financial crisis exposed yet another set of weaknesses even in the regulatory reforms being adopted in the post-2008 scenario. The crisis in the EU while revealing fragility and incompleteness of globalization and integration phenomena, has also exposed that reform process must redress weaker theoretical and conceptual foundations of the regulatory philosophy that bred the current crisis. For example, financial, political, fiscal and monetary conflicts within the Union in the post-2010 period have, if not negated, yet successfully challenged integration protagonists, and the talks on two-speed euro make a point in this regard, as also said by George Stigler, that ‗a war can ravage half a continent and raise no issues in economic history‘. The rising sovereign debt crisis in the EU and fiscal imbalances between the traditional western block and fairly advanced emerging market economies has already been translated into a steady decline of the western dominance and influence in the rest of the world. Global financial governance and policy formulation processes that used to be typically driven by powerful western economies, now have to undergo substantive adjustments per the new economic and political power shifts that have taken place in the financial world. And, this adjustment process is happening fast. Regulatory institutions make the core part of the international financial system and constitute very critical pillar supporting the pyramid of economic globalism, not only now but since 1920.3 Experience has demonstrated that although improper supervisory arrangements have exacerbated several recent systemic banking crises yet the issue of financial sector regulatory and supervisory independence (RSI) has received only marginal attention in literature and practice.4 Quintyn and Taylor have shown that RSI is important for financial stability for the same reasons that central bank independence is important for monetary stability. Requisite institutional framework however, is not in place to make independence work in practice. This paper is particularly exploring the basic issues of ‗whether‘ and ‗how to co-operate‘ on these regulatory and supervisory mechanisms. This would serve two purposes: firstly, it will steer the reform process by bringing requisite amount of reforms at areas that await comprehensive reforms; and secondly, given the established role of the IFRA in maintaining financial stability (section I, B), this research helps in identification of structural issues of the architecture with a view to modify and reform (section III).5 2 Eichengreen, B., & Park, B. (Eds.). (2012). The World Economy After The Global Crisis: A New Economic Order for the 21st Century (Vol. 19): World Scientific Publishing Company Incorporated;p.1 3 See, Brummer, C. (2012). Soft law and the global financial system: rule-making in the 21st century. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. (p.6) 4 Quintyn, M., & Taylor, M. (March 2002). Regulatory and Supervisory Independence and Financial Stability. IMF Working Paper No. 02/46, available at SSRN: http://ssrn.com/abstract=879439, 1-54. 5 Parts of section III have been partly drawn on an on-going joint project by Douglas Arner, Emilios Avgouleas and Uzma Ashraf, for an ADB study. 2 Proceedings of 8th Annual London Business Research Conference Imperial College, London, UK, 8 - 9 July 2013, ISBN: 978-1-922069-28-3 The analysis in this chapter has a broader coverage of issues that directly stem from the nature of the architecture based on post-crisis regulation - or as is more generally popular in current literature - the re-regulation derive, the set-back to liberalization hype (against the policy of protectionism which is especially being followed by Asian economies through checks on free convertibility of their currencies) weak crisis management and prevention mechanisms, ineffective role of support institutions which lack legal backstops for an effective enforcement of uniform regulatory standards and risk-sensitive preventive measures. These factors have contributed to the failure of both, the existing institutional structures and the leading regulatory standards that resulted into a poorly performing international financial regime. The argument here also builds up the analysis around the ‗infamous‘ trade-off between sovereignty costs and collective efforts at internationalization of global standards necessitated by the essential globalized nature of the financial markets, financial products, financial processes and requisite interests. Section II, A of this research looks at the theoretical underpinnings of the relationship between institutions and financial market development. This has employed threepronged strategy by looking at: institutions and development; their relationship with law; and how the nexus has developed over time and took its present shape. Part B of this section while defining the ‗undefined‘ term, ‗financial stability‘ takes the debate on financial markets further by bringing in the ‗instability‘ factor and pins down its inherent challenges – foremost of that stems from financial liberalization and the risks that this unrestrained trend has brought in its wake. Last part of this section applies theoretical conceptualizations with the real responses that flew in the post-2008 era to re-assert irrefutable significance for the need to have consolidated responses and on the role of financial institutions in maintaining financial stability. Section III focuses on the post-crisis responses and picks up on the EU financial market development and economic, monetary and institutional challenges at the foundations of the Union itself. Final part of this section draws on the current reform taking place at the EU in response to the crisis to highlight fundamental ‗gaps‘ and ‗wrongs‘ that this reform package is again committing itself to and that may form breeding ground for any future crisis. II. Conceptualizing the Relationship of Institutions & Financial Markets This section discusses theories of development in relation to institutions and their role in the advancement of international financial markets where law, in the 21 st century, has assumed a pivotal position. A. Institutions Matter for Financial Markets Development From the beginning of the 21st century, financial markets and institutions were taken as if these are complete and near perfection, therefore, neither these require much regulation nor is the topic itself in want of more research for forecasting financial risks or economic crisis. The study of financial institutions was regarded by many economists as 3 Proceedings of 8th Annual London Business Research Conference Imperial College, London, UK, 8 - 9 July 2013, ISBN: 978-1-922069-28-3 unimportant.6 Although financial markets were seriously affected during the crisis episodes of 1990s and early 2000‘s but due to the limited geographic spread of crisis incidence - mainly in developing markets - the mainstream economists considered the scope is of little relevance to the developed financial markets in industrialized countries. Even the crisis in Japan – the second largest economy of the world - during the 1990s and 2000s and Scandinavian crisis of 1990s could hardly grasp any attention from the macroeconomists.7 It is not surprising therefore, that the reform process, in the sixth year after the crisis, still awaits significant bounds. 1. Law, Institutions and Development Nexus The significance attached to the importance of institution-building and the scale of institutional development remained variegated in the developed and the developing world; where the former deliberately cultivated strong institutional norms while the later due to varied domestic idiosyncratic preferences including lack of appropriate resources, and external factors which arose mostly from colonial legacy and their insignificant share in the global financial activity - could not keep pace with the institutional sophistication augmented in the industrialized world. The industrialized world however itself paid very little attention to the widening gap between theory and practice of the one hand, while, on the other, the disconnect between theorizing the law and its correlations with stability and development increased further. Efforts at exploring the nexus between law and development have failed for decades.8 2. The Current State of Law, Development and Institutions Law and development efforts have now spanned more than half a century. The labels have changed over time: in the fifties, sixties, and seventies it was called the ―law and development movement‖ in the eighties and nineties, through the turn of the century, it morphed from ―good governance programs‖ to ―rule of law and development.‖ The prospects are worse for law and development than for other elements of the modernization package. The past thirty years have demonstrated that components of capitalism (introducing market mechanisms, securing financing, establishing factories and production chains) and democracy (instituting periodic elections) can be implemented through the creation of new institutional arrangements that function effectively— although they will not work the same or have the same consequences as in the West.9 The collapse of the ―Washington Consensus‖ and later financial crisis in the western economies in 2007-08 has shaken the confidence of development theorists who now admit that they have no reliable knowledge about how to generate economic development. 6 Allen, F. (2001). Do Financial Institutions Matter? Center for Financial Institutions, University of Pennsylvania, Working Papers number 01-04. Available at http://fic.wharton.upenn.edu/fic/papers/01/0104.pdf 7 Allen, F., & Carletti, E. (2011). New Theories to Underpin Financial Reform. Journal of Financial Stability. doi:10.1016/j.jfs.2011.07.001 8 Tamanaha, B. Z. (2011). The Primacy of Society and the Failures of Law and Development. Cornell International Law Journal, 44, http://www.lawschool.cornell.edu/research/ilj/upload/tamanaha-final.pdf. 9 Tamanaha, B. Z. (2011) 4 Proceedings of 8th Annual London Business Research Conference Imperial College, London, UK, 8 - 9 July 2013, ISBN: 978-1-922069-28-3 B. International Financial Stability: Are There Inherent Challenges? In the aftermath of the 2008 crisis, financial stability has emerged as one of the prime objective to the reform process. This section, while defining financial stability, leads the debate to describe the financial systems, esp. as it exists now, to underpin the interrelationship of systemic risk and financial market liberalization. 1. What is Financial Stability? Lack of financial stability - both nationally and internationally - can be an important obstacle to growth, development and poverty reduction. Financial stability is now considered as a ‗global public good‘ while financial instability is characterized as a ‗global public bad‘ because it spreads across countries through negative externalities and that collective action problems have led so far to an under provision of the international public good of financial stability.10 Given the large number, frequency, severity and higher societal as well as financial cost of recent crises, much emphasis in recent writing has been on combating the global public bad of financial instability. Defining the Undefined Term In the more recent literature after the 2008 crisis that has significantly changed the perspectives, and where defining the ‗financial stability‘ has grown from a ‗homely‘ exercise to much more complex international concept, the condition may now be described ‗in which the financial system - comprising of financial intermediaries, markets and market infrastructures - is capable of withstanding shocks, thereby reducing the likelihood of disruptions in the financial intermediation process which are severe enough to significantly impair the allocation of savings to profitable investment opportunities.‘ A stable financial system displays the following three key characteristics: a. Allowing efficient and smooth transfer of resources from savers to investors. b. A reasonable and accurate risk pricing and assessment. c. Able to comfortably absorb financial and real economic surprises and shocks. Understood this way, the safeguarding of financial stability requires identifying the main sources of risk and vulnerability such as inefficiencies in the allocation of financial resources from savers to investors and the mis-pricing or mismanagement of financial risks.11 Gari Schinasi defines financial stability as an ability to facilitate and enhance economic processes, manage risks, and absorb shocks. He considers financial stability along a continuum which is changeable over time and is consistent with multiple combinations of the constituent elements of finance. In other words, 10 Wyplosz C., 1999, Economic policy coordination in EMU: strategies and institutions, mimeo, http://hei.unige.ch/~wyplosz/cw_bonn_final.PDF (check out the reference?) 11 ECB. (December 2012). Financial Stability Review: European Central Bank, available at http://www.ecb.europa.eu/pub/pdf/other/financialstabilityreview201212en.pdf?fd9bfe9f040ef32a1195c076 7d6427f3. 5 Proceedings of 8th Annual London Business Research Conference Imperial College, London, UK, 8 - 9 July 2013, ISBN: 978-1-922069-28-3 ‗a financial system is in a range of stability whenever it is capable of facilitating (rather than impeding) the performance of an economy, and of dissipating financial imbalances that arise endogenously or as a result of significant adverse and unanticipated events.‘12 2. The Link between Finance and Financial Market Liberalization It is useful to put crises and responses to them in historical context. Firstly, it is important to stress that after the Great Depression, the financial sector – particularly, but not only, in the US – was re-regulated carefully, most notably by the Glass- Steagall Act of 1933. During the next 40 years, the financial sector was closely regulated, capital accounts were essentially closed, and there were practically no significant financial crises. However, since the 1970‘s there has been far-reaching deregulation, both at national and international level. Financial liberalization is the greater access to international capital, facilitated in part through an expanded role for foreign banks and non-bank financial institutions. The definition of financial liberalization, therefore, can be contrived in terms of following aspects:13 a. Elimination of interest rate controls, b. Lowering of bank reserve requirements, c. Independence of banks in their lending decisions; i.e., no interference from the government machinery d. Privatized banks, and no nationally owned bank by the central government e. Freedom to foreign banks to compete in the market, and f. Facilitation and encouragement of capital inflows Another view presents financial liberalization as the stronghold of finance capital over the State. The basic aim of the process is to liberate finance from the control by the State; however, in praxis it is the state that acquiesce the control to finance, therefore, financial liberalization demands: the autonomy of the Central Bank from the government, complete freedom of finance to move into and out of the economy, which implies full convertibility of currency, the abandonment of all "priority sector" lending targets, an end to government-imposed differential interest rate schemes and freeing of interest rates, and, the complete freedom of banks to pursue profits unhindered by government directives; removal of restrictions on the ownership of banks, and so on. 12 Schinasi, G. J. (October 2004). Defining Financial Stability. IMF Working Paper, International Capital Markets Department, available at http://cdi.mecon.gov.ar/biblio/docelec/fmi/wp/wp04187.pdf, WP/04/187, p.9. See also, Schinasi, G. J., & (June 2003). Responsibility of Central Banks for Stability in Financial Markets IMF Working Paper No 03/121, Available at SSRN: http://ssrn.com/abstract=879197, 1-19. 13 Beim, D., & Calomiris, C. (2001). Emerging Financial Markets New York: McGraw-Hill. 6 Proceedings of 8th Annual London Business Research Conference Imperial College, London, UK, 8 - 9 July 2013, ISBN: 978-1-922069-28-3 Modern financial markets are characterized by: Global: the markets marked with high capital mobility are global in nature at the wholesale level but at best are international at the retail level. Competition: fierce competition among financial services providers Monetary system: the dominant monetary system is based on floating rates between major currencies, and many other currencies have pegged their currencies to the major currencies through various mechanisms. Historical separation between financial services, providers and actors stands at the minimum, esp in the pre-2008 era, the historical boundaries were blurred deliberately. Capital flows: largely unrestricted and widely dispersed Financial crises: frequent, and marked with strong contagions Risk: has emerged as the major factor in monitoring, supervising and regulatory activities and thereby, it has increased the costs for investors, regulators and financial institutions. Financial innovations Co-existence: of regulated market simultaneously with a large and liquid unregulated institutional market. International cooperation: extensive and rising though financial and trade market connectivity, development and cooperation. IFIs: primarily driven by the EU, WTO, FSF/ FSB, EBRD, BIS and through its technical committees on banking, securities and related standards. Dominant economic philosophy: liberalization and de-regulation under the Washington consensus, until the financial crisis of 2008; the aftermath is primarily marked with risk-management, integration, reform of regulatory and legal institutions. Since all finance is a measurement of ‗risk‘, from an economic perspective, banking, securities and insurance products are all variations on a theme.14 The management of these markets obligates appropriate risk apparatuses in place, the reforms underway are, therefore, targeting re-regulation in a way to address systemic risk, innovations and instability dynamics. 3. Financial Market Liberalization and Systemic Risk: Are They Connected? Globalization has brought many advantages to the world especially of finance, but among many not-so-good implications, systemic risk stands out as the most threatening. It is famously said, the market foresees everything except the crises. The natural state is a ‗state of war‘ and a ‗state of peace‘ is not, for Kant, and would never be, the automatic product of a scientific calculation or in any way simply ‗a natural‘ state. It is something that must be established, not through technical means or partial 14 Ferran, E., Moloney, N., Hill, J. G., & John C. Coffee, J. (Eds.). (2012). The regulatory aftermath of the global financial crisis Cambridge, UK ; New York : Cambridge University Press. 7 Proceedings of 8th Annual London Business Research Conference Imperial College, London, UK, 8 - 9 July 2013, ISBN: 978-1-922069-28-3 adjustments but by political, and must be expressly established. The persistence of global financial imbalances structurally vitiates/ debases the possibility of global, political and economic peace. And the ‗endless finance‘ that is, finance based on ‗perpetual postponement‘ of payments is one of the primary obstacles to perpetual peace, contended Kant. ‗It will be commerce to avoid war‘, as he further contends, so it is the system of ‗perpetual alliances‘ to avoid war or to establish peace, an application of the contention. For the US and China, it is in mutual interest either to pay the debts accumulated or to demand its payment. These certainly are the ‗leges latae‘ and not ‗leges strictae‘, as unsaid conventions of warfare. But a perpetual peace is not a guarantee any more. The only difference the 21st century may have made in this ‗war and peace context from Kant‘s 18th century is that military terror of his time has been eclipsed by ‗economic seductions‘. Any robust system of regulation should have: financial infrastructure, especially payment and settlement system well in place, effective corporate governance systems, institutionalized and transparent disclosure requirements, effective monitoring of comprehensive bank activities, a lender of last resort institution to provide liquidity to financial institutions on an appropriate basis, f. a bank/ financial institution resolution framework readily available in times of crisis, and, g. appropriate rules and procedures to protect financial services consumers, such as deposit insurance. a. b. c. d. e. The global financial crisis has highlighted significant weaknesses in each of these parts of financial regulation design, which are currently being addressed by the G-20. C. The Trio at Work: Market Liberalization, Financial Instability and Institutional Responses This thesis taken up in this section is that institutions are important, and development of financial institutions directly is connected with the development of financial markets, financial systems and ultimately, economic growth and development of an economy. The emphasis has been on the adequacy rather inadequacy of support-institutions in financial markets when crisis in 2008 erupted, therefore, the argument draws on inadequate and ineffective responses that were extended by the states and regulatory institutions. 1. Institutions are Important The collapse of the Bretton Woods system in 1980s unleashed new forces of free market economy which weekend states‘ control mechanisms significantly. In particular, 8 Proceedings of 8th Annual London Business Research Conference Imperial College, London, UK, 8 - 9 July 2013, ISBN: 978-1-922069-28-3 with the fall of communism and failure of policy-based approaches, the foremost question that came to prominence - and was blown out of proportion by the followers of Friedrich Hayek, Milton Friedman - was how to facilitate transition from total stateowned controls to a functioning market-economy in the countries of the former Soviet Bloc.15 As the quick liberalization policies did not work very well so the realization imparted a new significance to the role of the institutions in economic development especially the issues of establishing formal mechanisms for establishing property rights, and related paraphernalia of support-providing legal institutions in transition economies.16 There, the new institutional economics17 (NIE), took its new birth and was revived into literature by Douglas North.18 To define, NIE is an economic perspective that attempts to extend economics by focusing on the social and legal norms and rules that underlie economic activity and with analysis beyond earlier institutional economics and neoclassical economics.19 Most scholars doing research under the NIE‘s methodological principles followed Douglass North's demarcation between institutions and organizations. Institutions are the "rules of the game", as North elaborates meaning of ‗institutions‘, or, more formally, are the humanly devised constraints, consisting of both the formal legal rules and the informal social norms that govern individual behavior and structure social interactions (institutional frameworks).20 He further dilates upon the role of the institutions which provide the basic structure by which human beings throughout the history have created order and attempted to reduce uncertainty in exchange. …they connect the past with the present and the future so that history is largely an incremental story of institutional evolution in which the historical performance of the economics can only be understood as part of a sequential story.21 2. Dichotomy of Political and Financial Institutions – Who Matters More? Political institutions have an advantage over the IFIs. It is hard for the unelected central 15 Arner, D.W. (2007). Financial Stability, Economic Growth and the Role of Law: Cambridge University Press. P. 16 16 See, for reference, Elinor Ostrom (2005). "Doing Institutional Analysis: Digging Deeper than Markets and Hierarchies," Handbook of New Institutional Economics, C. Ménard and M. Shirley, eds. Handbook of New Institutional Economics, pp. 819-848. Springer. Also, Oliver E. Williamson (2000). "The New Institutional Economics: Taking Stock, Looking Ahead," Journal of Economic Literature, 38(3), pp. 595613. 17 See, Ronald Coase (1998). "The New Institutional Economics," American Economic Review, 88(2), pp. 72-74. See also, Ronald Coase, (1991). "The Institutional Structure of Production," Nobel Prize Lecture, reprinted in 1992, American Economic Review, 82(4), pp. 713-719. Available at http://www.nobelprize.org/nobel_prizes/economics/laureates/1991/coase-lecture.html 18 Douglass C. North (1995). "The New Institutional Economics and Third World Development," in The New Institutional Economics and Third World Development, J. Harriss, J. Hunter, and C. M. Lewis, ed., pp. 17-26. 19 Malcolm Rutherford (2001). "Institutional Economics: Then and Now," Journal of Economic Perspectives, 15(3), pp. 185-90 (173-194). 20 Douglass C. North, (1990), Institutions, Institutional Change and Economic Performance, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p 3 21 Douglass C. North, (1990) p.118 9 Proceedings of 8th Annual London Business Research Conference Imperial College, London, UK, 8 - 9 July 2013, ISBN: 978-1-922069-28-3 bankers and regulators to wield power on the politically elected office bearers. Although for Keynes, he tenaciously expected that ideas would retain pre-eminence over power politics22 but issues of ‗power‘ are hard to circumvent when it comes to economic paradigms and market interests. Mainstream economics also stubbornly denies a bigger role of power dialectics. However, the ideas and institutions within which the current global crisis is being addressed reflect the power structures of the past and are under pressure to evolve. Many have argued for example that the current crisis was the result of neoliberal ideology.23 This ideology in turn has conditioned the mainstream analysis of the crisis and the policy response in a complex way.24 To many it has seemed clear that mainstream analysis not only signally failed (in predicting and analysing the crisis) but also provided very little theoretical justification for the interventionist policy measures taken in the early stages of the crisis.25 III. The Big Bang & the EU Financial Reforms: An Unfinished Agenda As the crisis intensifies, the EU had to devise mechanisms in the midst of the crisis: firstly, to prevent an immediate meltdown of its banking sector and ensuing chain of sovereign bankruptcies and, secondly, to reform its flawed institutions, in order to prevent the Eurozone architecture from collapsing, that is, Eurozone members had to build both a crisis-fighting capacity and support bailout funding mechanisms. The Eurozone crisis has exposed the potential risks of financial market interconnectedness where shocks appearing in one part of the market can be transmitted widely and quickly across all other parts. Examples of such rapid transmission of shocks include the failure of Icelandic banks, the botched rescue of Fortis bank, the threat of collapse of the financial system (for example of Ireland and Spain), and the possibility of a sovereign default (e.g., Greece). A. Interplay of Growth, Development and Financial Instability Following the escalation of the sovereign debt crisis in the second half of 2011, the EU economy entered a shallow recession by the fourth quarter of the same year. Since then, the outlook for the EU economy slowly improved in the beginning but the situation 22 Keynes, J. M. (1936). The General Theory of Employment, Interest and Money. London: Macmillan; reprint 1973, Collected Writings, vol. VII, London, Macmillan for the Royal Economic Society. 23 See for example, Palma, J. G. (2009). The revenge of the market on the rentiers. Why neo-liberal reports of the end of history turned out to be premature. Cambridge Journal of Economics, 33(4), 829869. 24 For example, see, Callinicos, A. (2012). Contradictions of austerity. Cambridge Journal of Economics, 36(1), 65-77. 25 Dow, A., & Dow, S. (2013). Economic history and economic theory: the staples approach to economic development. Cambridge Journal of Economics. doi: 10.1093/cje/bet021, see also, Allen, F., & Carletti, E. (2011), who point out institutional theoretical gaps. 10 Proceedings of 8th Annual London Business Research Conference Imperial College, London, UK, 8 - 9 July 2013, ISBN: 978-1-922069-28-3 became extraordinarily fragile and by mid-2012 the risk of a renewed crisis became more evident. The intensification of the sovereign-debt crisis in the first half of the year, raised market concerns about the long-term viability of the euro area itself and the negative fall-out from banks' funding pressures and economic activity, together with an unexpected slowdown in non-EU GDP growth and global trade contributed to an overall disappointing global growth performance. The annual GDP growth rate predicted is 0.5 percent for the EU in 2013, whereas GDP in the Eurozone will remain unchanged. 26 The weak short-term growth outlook raises concerns for the labour markets, where a further rise in already very high unemployment rates appears likely for this year as Italy, Portugal, Greece, Cyprus, Portugal and Spain implement austerity measures to reduce their debt through asset sales and reduced spending in social welfare programs. These circumstances have given birth to a new set of bank authorization, supervision and resolution arrangements: the European Banking Union. However, the European Banking Union, plausible and necessary as it may be, has also reinforced rather than calmed the centrifugal forces within the EU and has the potential to lead to a serious split of the internal market.27 Important members of the EU, chiefly the UK, have resolutely remained outside important European Banking Union arrangements. It is, thus, reasonable to infer that political expediency and not economic necessities will, in the end, seal the fate of the single currency. B. The EU Financial Reforms Above two sections have focused on the theoretical and conceptual foundations of ‗institutions‘ and their role in market stability and economic development. The section below will take the case of the EU to see – which as a single market provides a laboratory to analyze pre-and-post-crisis developments taking place on the financial realm - if it still provides a template of ‗a successful institutional mechanism‘ capable of providing stability to the global financial system.28 Haldane has captured the regulatory weaknesses in a most comprehensive but precisely brief way. He narrates, catching a frisbee is difficult. Doing so successfully requires the catcher to weigh a complex array of physical and atmospheric factors, among them wind speed and frisbee rotation.29 Yet despite its complexity, catching a frisbee is remarkably common. It is a task that an average dog can master. So what is the secret of the dog‘s success? The answer is simple. For studies have shown that the 26 EU. (Autumn 2012). European Economic Forecast (Vol. European Economy: 7|2012). European Commission: Directorate-General for Economic and Financial Affairs. 27 Lastra, R. (2013). Banking Union and Single Market: Conflict or Companionship?, Fordham International Law Journal, Vol. 36, forthcoming. 28 This section partly draws on a joint work by Douglas Arner, Emilios Avgouleas, and Uzma Ashraf for an ADB on-going project on regional financial integration. 29 Haldane, A. G. (2012). The dog and the frisbee The Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City’s 36th economic policy symposium, “The Changing Policy Landscape”, Jackson Hole, 31 August 2012. Wyoming.http://www.bankofengland.co.uk/publications/Documents/speeches/2012/speech596.pdfhttp://w ww.bis.org/review/r120905a.pdf 11 Proceedings of 8th Annual London Business Research Conference Imperial College, London, UK, 8 - 9 July 2013, ISBN: 978-1-922069-28-3 frisbee-catching dog follows the simplest of rules of thumb: run at a speed so that the angle of gaze to the frisbee remains roughly constant. Catching a crisis, like catching a frisbee, is difficult. Doing so requires the regulator to weigh a complex array of financial and psychological factors, among them innovation and risk appetite. Yet despite this complexity, efforts to catch the crisis frisbee have continued to escalate. Ever-larger litters have not, however, obviously improved watchdogs‘ frisbee-catching abilities. It still remains an ‗unfinished agenda‘. No regulator had the foresight to predict 1. The EU Financial Market Development and Challenges of Integration Problems inevitably arise when a supra-national market exhibits a high degree of integration but the development of cross-border regulatory mechanisms lags significantly behind that is, a clear lack of foresight to predict crisis on the part of the regulators. The journey to the development of a single financial market in Europe lagged significantly behind on establishing matching regulatory spheres. It was inevitable therefore, that the crisis exposed such huge regulatory gaps both within national regulation and in supra-national networks. In this context, this section will provide an analytical overview of the financial market development in the EU and the challenges that this integration process posed vis-à-vis stability of the market. The establishment of a single currency area (the Eurozone) was another leap forward in the development of single market. Both, the single currency and pan-European banks necessitated matching establishment of requisite support-institutions for regulation of cross-border large-scale businesses and transactions within the integrated market. The recent crisis have however, exposed blatantly this fatal ‗trade-off‘. Economic and financial market growth of both the individual member-states and of the Union was given obvious preference over financial market stability. It raised questions about longterm protection of EU-wide financial stability in the absence of appropriate institutional arrangements.30 The so-called financial stability trilemma,31 which states that the (three) objectives of financial stability, financial integration, and national financial policies cannot be combined at the same time, has precisely described the acute policy tradeoff which holds that one of these objectives has to give in to safeguard the other two. 32 In spite of assertions to the contrary,33 the recent crisis has proven beyond doubt that a common currency area is not viable without building, at the same time, transnational supervisory structures in the field of fiscal monitoring and responsibility and bank supervision. 30 See for details, Schoenmaker, D., & Oosterloow, S. (2005). Financial Supervision in an Integrating Europe: Measuring Cross-Border Externalities. International Finance, 8(1), 1–27. 31 See, Schoenmaker, D. (February, 2011). The Financial Trilemma. Duisenberg School of Finance Amsterdam & Finance Department VU University Amsterdam; Tinbergen Institute Discussion Paper; Forthcoming in Economics Letters, 7. See also, Thygesen, N. (2003). Comments on The Political Economy of Financial Harmonisation in Europe. In J. Kremer, D. Schoenmaker & P. Wierts (Eds.), Financial Supervision in Europe: Cheltenham: Edward Elgar. 32 Lastra, R. M., & Louis, J.-V. (2013). European Economic and Monetary Union: History, Trends, and Prospects. Yearbook of European Law. 33 See Tommaso Padoa-Schioppa, The Road to Monetary Union in Europe: The Emperor, the Kings and the Genies (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2000). 12 Proceedings of 8th Annual London Business Research Conference Imperial College, London, UK, 8 - 9 July 2013, ISBN: 978-1-922069-28-3 2. Challenges of Economic and Monetary Institutionalization The establishment of the Euro as the common currency of seventeen EU member states (as of today) has been the product of political expediencies as much as of economic efficiency rationales. However, in the background of recent crisis it has witnessed major crises and setbacks.34 Apart from finding mechanism to address this ‗financial trilemma‘ in the EU integrated market, the arguments on having a ‗two-speed euro‘, and related alternative prepositions, pull dark shadows on newer financial developments. The European Monetary System (EMS) was created in 1979,35 in order to manage and control currency fluctuations among EMS members and was viewed as the first step towards permanent exchange rate alignment and paved the way towards the establishment of European Economic and Monetary Union (EMU). These were the economic developments. However, the founding objective of these developments was not merely economic or financial only. The establishment of the single currency was itself a matter of politics as much as of economic necessity. Through a currency union, EU members could answer the classic monetary trilemma, which is built on the Mundell-Fleming model of an open economy under capital mobility.36 The monetary trilemma famously states that a fixed exchange rate, capital mobility, and national monetary policy cannot be achieved at the same time; one policy objective has to give. Therefore, under capital mobility and national monetary policy, fixed exchange rates will invariably break down.37 However, as the EU has been very far from being an optimal currency area under the Mundell model, 38 and there was no fiscal integration or debt mutualization it was only a matter of time before the first strains would appear. It is, thus, arguable that the founders of the EMU just hoped that a single currency would pave the way for a fiscal and political union, in the 34 See P Pierson, ―The Path to European Integration: A Historical Institutionalist Analysis,‖ Comparative Political Studies, 29 (1996), 123-63 and J. Story and I. Walter, Political Economy of Financial Integration in Europe: The Battle of the Systems (Manchester University Press, 1997). 35 See, Resolution of the European Council of 5 December 1978 on the establishment of the European Monetary System (EMS) and related matters (1978) Bulletin of the European Communities. December, No 12, pp 9–13. Regulations Nos 380 and 381/78, 18 December 1978,OJEC, No L379, 30 December 1978 (and their modifications); Agreement of 13 March 1979 between the central banks of the Member States of the European Economic Community laid down the operating procedures for the European Monetary System. Available at http://ec.europa.eu/economy_finance/emu_history/documentation/compendia/a791231en1771979compe ndiumcm_a.pdf See for analysis, Giavazzi, F., & Giovannini, A. (1989). See also, Marcello De Cecco, A. G. (Ed.). (1989). 36 See, Mundell, R. A. (1963). Capital Mobility and Stabilization Policy under Fixed and Flexible Exchange Rates. Canadian Journal of Economics, 29, 475-485 available at http://jrxy.zjgsu.edu.cn/jrxy/jssc/2904.pdf 37 See, Obstfeld, M., Shambaugh, J. C., & Taylor, A. M. (2005). The Trilemma in History: Tradeoffs among Exchange Rates, Monetary Policies, and Capital Mobility. Review of Economics and Statistics, 87, 423-438. 38 Mundell, R. A. (1961). A Theory of Optimum Currency Areas. American Economic Review 51 (4): 657– 665 13 Proceedings of 8th Annual London Business Research Conference Imperial College, London, UK, 8 - 9 July 2013, ISBN: 978-1-922069-28-3 long run - something that has not yet happened. The talks for having a ‗two-speed euro‘ and a further shrinking euro-zone have already assumed a central position in the deliberations on the subject when it comes to steer the future of the ‗euro‘. The early Eurobond market might have played the role of an imperfect substitute to financial integration, given that capital mobility was only a secondary EU goal until the 1990s. 39 The 1966 Segré report was both very cognizant of the growth potential attached to financial integration and of the potential for this objective to be confounded by commercial interests.40 The EU regulatory regime based on minimum harmonization had weaker foundations. A multi-level governance system involves far more complexities than a regime based on minimum harmonisation can foresee. These mainly arise out of conflicting and sometimes misunderstood national priorities and transnational requirements. Even before the current crisis, the European Union was viewed by some as a ‗too intrusive‘ and ‗remote‘ institution in need of a more coherent set of policies within existing treaties.41 Iv. Concluding thoughts: Where is the Promise to Stability? It is too early to put a caption to this second decade of the 21 st century and to predict where it would lead ultimately but what is certain is that a change from old patterns which were marked by extreme globalization, integration and de-regulation has already commenced. It could be anything but continuation of the old financial, monetary, fiscal and even political globalist trends (nationalism is assuming a front seat). And the regulatory front is not an exception. The missing elements include apart from several other factors, accountability and legitimacy of regulations and supervisory practices. The missing elements include apart from several other factors, accountability and legitimacy of the regulations and supervisory practices. Also, given the peculiar nature of the shift triggered in the post-2008 and post-2010 crises, it is perhaps an apt moment to analyse the weaknesses, problems, and issues with the existing regulatory architecture. Regulators have become both competitors and essential partners in the international financial system, with varying and, at times, changing incentives with respect to whether and how and how much to co-operate on issues demanding concern. Weaknesses in the institutional framework have affected EU financial integration in two ways: firstly, the incomplete or partial harmonization of the pre-crisis supervisory and 39 Robert Genillard, ―The Eurobond Market‖ (1967) 23:2 Financial Analysts J. 144. See also Kurt Richebacher, ―The Problems and Prospects of Integrating European Capital Markets‖ (1969) 1:3 J. Money, Credit & Banking 337. 40 See Claude Segré et al., The Development of a European Capital Market: Report of a Group of Experts appointed by the EEC Commission (Brussels: European Economic Community, 1966). Segré argued for harmonization of non-retail national markets in ways later encouraged by the Eurobond market. 41 COM. (2001). European Governance - A White Paper. Brussels: Commission of the European Communities. P12 14 Proceedings of 8th Annual London Business Research Conference Imperial College, London, UK, 8 - 9 July 2013, ISBN: 978-1-922069-28-3 regulatory framework prevented the benefits of full integration from being reaped and created fragilities in the financial sector to build up in a way that became threatening over time and, secondly, the crisis revealed the vulnerabilities and gaps in the national and EU-wide crisis management frameworks. These weaknesses have resulted in partial disintegration of the internal market and have caused splits along national lines of some segments of the single EU market for capital and financial services. Thus, for the EU, progression to a framework of tighter financial integration and risk controls for the banking system – together with improved governance standards in the monetary and fiscal spheres and centralization of responsibility for financial stability – has become a one-way road. It is too early to put a caption to this second decade of the 21st century and to predict where it would lead ultimately but what is certain is that a change from old patterns which were marked by extreme globalization, integration and de-regulation has already commenced. It could be anything but continuation of the old financial, monetary, fiscal and even political globalist trends (where nationalism assuming a front seat). And the regulatory front is not an exception. The missing elements include apart from several other factors, accountability and legitimacy of the regulations and supervisory practices. Also, given the peculiar nature of the shift triggered in the post-2008 and post-2010 crises, it is perhaps an apt moment to analyse the weaknesses, problems, and issues with the existing regulatory architecture. Regulators have become both competitors and essential partners in the international financial system, with varying and, at times, changing incentives with respect to whether and how and how much to co-operate on issues demanding concern. Following factors hinder advancements on international cooperation on governance reforms: a. reluctance of the Europeans to give up disproportionate representation in the governance of international regulatory institutions b.There is a lack of ‗coherence‘ in the new players that have emerged recently on the global governance framework. Willingness to share sovereignty is even less in them than the dominant western faction. Why the financial sector is not safer today than it was it was six years ago despite making ‗real‘ progress on regulatory and financial reforms – is the question that hints neatly on the challenges that loom large on ‗still uncertain‘ financial horizon. Moreover, what is missing is: • Political resolve, which is required to address medium-term fiscal adjustment needs in several advanced countries, including the United States and Japan, which have yet to take decisive action in this area. • There is need to timely guard against overheating and the build-up of financial imbalances—with strong credit growth, rising inflation, and surging capital inflows especially in emerging Asia and Latin America. • Macro prudential tools, such as higher reserve requirements cannot be emphasized wrongly. We are now in a new phase of the crisis – the political phase – and tough political decisions need to be made. Time is of the essence. 15