Proceedings of Annual South Africa Business Research Conference

advertisement

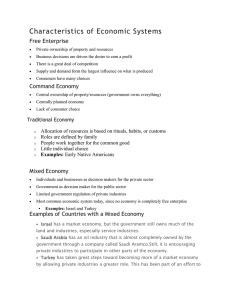

Proceedings of Annual South Africa Business Research Conference 11 - 12 January 2016, Taj Hotel, Cape Town, South Africa, ISBN: 978-1-922069-95-5 Saudization and the Nitaqat Programs: Overview and Performance Rita O. Koyame-Marsh The limited success of the Saudization program in curbing the unemployment of Saudi Nationals led the Saudi Ministry of Labor to introduce, a supplemental policy called the “Nitaqat” in 2011. The Nitaqat program has clear and well formulated policies that are expected to help the country efficiently reach the target rate of Saudization set in the national development plan. The paper gives an overview of the Saudization and the Nitaqat program, looking at their performances during the eighth (2005-2009) and the ninth (2010-2014) development plans. Data show that the Nitaqat has had some successes such as significantly increasing the number of Saudi employed in the private sector and moving private companies out of the unsafe zones. However, Nitaqat has not been able to reduce the persistent higher unemployment rate among Saudis while at the same time causing the exacerbation of the phenomenon of Ghost Saudization and the closure of more than 200,000 firms in two years. The expectation is that the implementation of the third phase of the Nitaqat would help resolve some these issues. Field: Labor Economics I. Introduction Saudi Arabia continued dependence on foreign labor mixed with rising unemployment of Saudi nationals has been a challenging problem for the Saudi Ministry of Labor (MoL) since the first Development Plan in 1970. To tackle this problem, the MoL introduced a nationalization program called “Saudization” which means the replacement of foreign workers with Saudi Nationals. A targeted Saudization or nationalization rate for the labor market is usually set in the Ministry of Economy and Planning’s (MOEP) Five-Year Development Plan (DP). However, these target rates are often not reached due to various reasons including the availability of cheaper foreign labor hired in masses by the private sector, the Saudi nationals’ lack of training and preparedness for the labor market, and the inefficiency of Saudization policies. The failure of the Saudization program in curbing the unemployment of Saudi Nationals, led the MoL in 2011 to introduce the Nitaqat program as a re-enforcement policy. Nitaqat which means “bands” or “zones” is designed to provide companies with more attainable targets. It imposes sanctions to companies in non-compliance and provides incentives to those firms in compliance in order to advance the Saudization agenda. The Nitaqat sanctions and incentives have been strictly enforced. However, one of the main concerns about the Nitaqat quotabased system is that it could put unnecessary burden on the private sector by _________________________________________________________________________ Dr. Rita O. Koyame-Marsh, College of Business Administration, Prince Mohammad Bin Fahd University, P.O. Box 1664, Al-Khobar 31952, Saudi Arabia, Email: rkoyame@hotmail.com, Phone: +966538714984 1 Proceedings of Annual South Africa Business Research Conference 11 - 12 January 2016, Taj Hotel, Cape Town, South Africa, ISBN: 978-1-922069-95-5 creating additional costs for companies, costs such as the costs of training Saudi Nationals so they can efficiently replace foreign workers [Looney 2004 and Ramady 2013). The burden on the private sector could potentially hinder economic growth and diversification if it leads to the closure of businesses and a decrease in foreign direct investment (FDI) inflows. This paper examines the performance of the Saudization program before and after the introduction of the Nitaqat program using data from the MOEP and Saudi Arabia Monetary Agency (SAMA). Moreover, the paper discusses the impediments to the Saudization program as viewed by the private sector and the potential success of the Nitaqat program in curbing the unemployment of Saudi nationals during the three years of its existence. The paper is organized as follows: section 2 give a brief review of the literature, while section 3 discusses the Saudization program and its performance in the eight DP. Section 4 gives an overview of the Nitaqat program and discusses its performance during the ninth DP. The paper finishes with a conclusion in section 6. II. LITERATURE REVIEW The literature on Saudization and the Nitaqat programs falls under the broad literature in labor economics that focuses on the impact of quota-based employment programs. The United States’ affirmative action program is the most studied quota based employment program in this literature. Affirmative action is a government-mandated program that imposes quotas on the employment of minority groups in government jobs and in jobs from private companies with government contracts in the United States. See Holzer & Neumark (2000) for a detailed survey of studies on the U.S. affirmative action program. Papers that have studied the effect of quota-based hiring policies in countries other than the U.S. include studies by Howard & Prakash (2012), Chin & Prakash (2011), and Prakash (2009) that examined the impact of Indian minority quota-based employment policies on the Indian labor market. They found that the hiring quota-based policies improved the employment outcome of some of the minority groups in India by increasing their probability of finding a salaried job and choosing higher-killed occupations which in turn led to higher household consumption expenditures. Additional studies in the literature focus on quota-based employment policies that are instituted for the purpose of nationalization of the labor force, especially in the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) countries – Bahrain, Kuwait, Oman, Saudi Arabia, Qatar, and the UAE. These countries’ reliance on foreign work force in the face of increasing national unemployment has forced their governments to enact and enforce quota-based hiring policies for their citizens. These are nationalization policies put in place as employment stimulus programs with the goal of increasing the employment of the nationals of these countries in the private sector These nationalization programs are referred to as Bahrainization in Bahrain, Kuwaitization in Kuwait, Omanization in Oman, Saudization in Saudi Arabia, Qatarization in Qatar, and Emiratization in UAE (Randeree, 2012). The focus of this paper is on Saudization policies of Saudi Arabia and their impact on Saudi labor market. The following are some of the recent studies on Saudization, the Nitaqat program, and the Saudi labor market: Harvard Kennedy School (2015), Peck (2014), Ramadi 2 Proceedings of Annual South Africa Business Research Conference 11 - 12 January 2016, Taj Hotel, Cape Town, South Africa, ISBN: 978-1-922069-95-5 (2013), Saudi Hollandi Capital (2012), Fakeeh (2009), and Al-Asmari (2008). Harvard Kennedy School (2015) wrote a background paper on Saudi labor market that resulted from its partnership with the Saudi Ministry of Labor represented by the Human Resources Development Fund (HRDF). The HRDF-Harvard partnership connects researchers with Saudi policy makers to generated in-depth knowledge of the current constraints in the areas of employment and job creation in the Kingdom. This report is not a comprehensive or conclusive or binding document. It is, however, a living document that focusses on identifying problems in the labor market and making headway into diagnosing the underlying causes of these problems. It promotes a smart policy design that encourages a collaborative and problemdriven scheme whereby parties use collective expertise to tackle important labor issues. Peck (2014) empirically analyses the effects of quota-based 2011 Nitaqat policies on nationalization, firm size, and firm exit in the Saudi’s private sector. The paper used a comprehensive data set on the full universe of Saudi private-sector firms to perform a regression kink. The regression kink results were then complemented with a differences-indifferences approach to estimate the overall effects of the program. The paper found that the Nitaqat program succeeded in increasing the employment of Saudi nationals but caused significant costs to private companies and the shutting down of approximately 11,000 private companies within 16 months of its implementation. Ramady (2013) discusses the Nitaqat program and examines its effect on the overall economic growth and productivity in Saudi Arabia assuming the introduction of a SAR 3,000 per month minimum wage for Saudi workers in the private sector under the government’s Hafiz system. The paper concludes that the Nitaqat program and the minimum wage policies would decrease labor productivity and potentially affect other Saudi government’s initiatives such as opening up the Saudi economy to the global market and raising the quantity of foreign direct investment (FDI) inflows. The study suggests that foreign firms could exit the Kingdom believing that Saudization policies will put them at a disadvantage, especially cost wise, when compared to their foreign competitors. In addition, potential new entrants will become more reluctant to invest in the Kingdom resulting in a reduction in FDI. Saudi Hollandi Capital (2012) also provides an overview of the Nitaqat program and discusses its effect on the Saudi’s economy. The paper highlights some of the factors that incited the Saudi government to launch the Nitaqat program, factors such as the unsuccessful implementation of the Saudization program, large presence of foreign employees, high unemployment rate among Saudis, increase in youth population, and unrest in the region. According to this study, the increase in the employment opportunities for Saudis and the reduction in outward remittances are the positive effects of the Nitaqat program while skills mismatch among local labor force, increase costs for private companies, fall in the inflow of FDI, and closure of businesses are the potential negative effects. Fakeeh (2009) wrote a doctorate thesis that discusses the paradox of high wealth and high unemployment of Saudi nationals in the Kingdom. He also attempts to determine if Saudization is the solution to the unemployment problem in Saudi Arabia by analyzing the shortcomings of the program as instituted by the government and as used by the private 3 Proceedings of Annual South Africa Business Research Conference 11 - 12 January 2016, Taj Hotel, Cape Town, South Africa, ISBN: 978-1-922069-95-5 sector. The study was conducted based on documented evidence as well as on interviews with representatives of key stakeholder groups such as policy makers, employers, and employees in Jeddah, Saudi Western Province. The study concludes that policy makers still view Saudization as an economic and social necessity while coming to the understanding of the difficulties that the policy presents to the private sector and the reluctance of the private sector in applying it. The study suggested that Saudization policies must fit the reality of the labor market in order to be more efficient. Al-Asmari (2008) gives some background information on the efforts made by the Saudi government in developing local manpower and replacing foreign labor with Saudi nationals through the Saudization program. The study concludes that more still need to be done in the development of local human resources and in reducing dependency on foreign labor in the private sector. Saudi government’s efforts and strides made at the education and training levels, the development of some job-replacement policies, and the creation of career opportunities are still not enough. The study also stresses the importance of harmonizing the education system with the actual needs and requirements of the labor market in Saudi Arabia. This paper adds to the recent literature on Saudization by providing updated information about the Nitaqat program and by comparing the performance of the Saudization program before and after the implementation of the Nitaqat during the eighth and ninth DPs. The paper offers clear evidence on the achievement of the Nitaqat program at effectively raising the number of Saudis employed in the private sector and the shortcomings of the program in reducing the level of unemployment for Saudi nationals. III. THE SAUDIZATION PROGRAM The Saudization program, which objective is to increase the number of employed Saudis, especially in the private sector, started with the first Saudi Government’s first DP in 1970 (1970 – 1975). However, it became a priority for the Saudi government in late 1990s due to rising unemployment for Saudi Nationals and a rapidly growing population with more than 50% under the age of 20 (Fakeeh, 2009). Currently, the government of Saudi Arabia has completed its ninth DP (2010-2014) and is working on its tenth DP (2015 - 2019). Table 1 gives a brief overview of the changes in Saudi labor force during the eight DP. The target Saudization rate (Saudi employment as percent of total employment) was set at 51.5 percent in the eighth DP (2005 – 2009). The expectation was that by the end of 2009, Saudi Nationals should represent 51.5 percent of the Saudi’s work force. However, for various reasons; the Saudization rate fell short of target, increasing only to about 47.9 percent at the end of the plan in 2009, missing its target rate by 40.8 percent (Ministry of Economy and Planning, 2010). In addition, there were 2.2 million new jobs created by the private sector during the five years of the eight DP, however only about 8.9 percent of them (195,755 jobs) were taken by Saudi Nationals (Sfakianakis, 2014). 4 Proceedings of Annual South Africa Business Research Conference 11 - 12 January 2016, Taj Hotel, Cape Town, South Africa, ISBN: 978-1-922069-95-5 Table 1 Saudi Arabia Main Indicators of Labor Market at the End of the Eight DP Actual Target Actual Percent Change Percentage(1) 2004 2009 2009 during 8th DP Above & Off Target Actual Target Saudi Manpower (Thousands) Male Female Saudi Labor Participation rate (%) 3804.2 3271.6 532.6 36.9 4886.0 3996.7 889.3 39.2 4329.0 3636.5 692.5 36.7 28.4% 22.2% 67.1% 6.2% 13.8% 11.1% 30.0% -0.5% (51.4 %) (50.0%) (55.3%) (108.1%) Total Employment (Thousands) Saudi Non-Saudi Saudization Rate (Saudi Employment as % of Total) Unemployed Saudis (Thousands) Male Female Saudi Unemployment Rate (% of Saudi Manpower) Male Female 8281 .8 3536.3 4745.5 42.7 9221.3 4747.1 4474.2 51.5 8173.1 3914.6 4258.5 47.9 11.3% 34.2% -5.7% 20.6% -1.3% 10.7% -10.3% 12.2% (111.5%) (68.7%) 75.4% (40.8%) 267.9 183.6 84.3 7.0 138.9 99.7 39.2 2.8 414.4 238.1 176.3 9.6 -48.2% -45.7% -53.5% -60.0% 54.7% 29.7% 109.1% 37.1% (213.5%) (165.0%) (303.9%) (161.8%) 5.6 15.8 2.5 4.4 6.5 25.5 -55.3% -72.1% 16.1% 61.4% (129.1%) (185.2%) Note: (1) A positive number means percentage above target. Negative numbers are in parenthesis and mean percentage off target. Source: Data from Ministry of Economy and Planning 2006a, 2006b, 2010a, 2010b, and 2010c. Percentage changes and percentage above & off target calculated by the author In addition, the unemployment rate for Saudi nationals was expected to decline from 7 percent in 2004 to 2.8 percent by the end of the eight DP in 2009. Unfortunately, rather than falling, Saudis’ unemployment rate rose to 9.6 percent in 2009, missing its target by 161.8 percent. Moreover, the number of unemployed Saudis which was targeted to decrease from 267,900 in 2004 to 138,900 by the end of 2009, increased to 414,400 unemployed Saudis, missing its target by 213.5 percent. While, the number of employed Saudi nationals rose as expected but fell short of target by 68.7 percent. Of all the labor market’s targets set by the MOEP in the eight DP, only one exceeded expectation, the number of employed foreign workers which declined by 10.3 percent, almost twice as the set target of 5.7 percent. This was good news for the MoL which at least managed to reach and exceed one of the key goals of the nationalization program, that is, the reduction in the number of foreign workers in the Kingdom. 3.1. Impediments to Saudization 3.1.1. Private sector Perspectives The literature presents several impediments to Saudization program. However, this study shall discuss the following four barriers as perceived by the private sector: Saudis’ lack of skills and work ethics, mismatch between acquired skills and required skills, lack of strategic planning by the government and the private sector, and increase costs to the private sector. 5 Proceedings of Annual South Africa Business Research Conference 11 - 12 January 2016, Taj Hotel, Cape Town, South Africa, ISBN: 978-1-922069-95-5 The first barrier to Saudization is the belief by the private sector that most Saudis lack skills and work ethics when compared to their expatriate counterpart. According to Fakeeh (2009), many business owners in the private sector think that Saudi nationals have an undesirable attitude towards work. They stated that Saudi workers behave as though they are above work while lacking knowledge and skills. In addition, Saudis are believed to be disrespectful towards companies’ laws; they lack discipline, and are unreliable. As a result, the private sector is reluctant to hire them. The following is a quote from the private sector concerning Saudis’ work ethics and attitude (Fakeeh, 2009; p.109): “Assuming I could train them on policy and procedure as well as how to use the computer, how am I supposed to teach them how to behave with patients and lend themselves to think and communicate appropriately for the work place. Manners, oh talk about manners! [Lebanese medical director, private hospital, Jeddah] The second stumbling block to Saudization is the mismatch between the skills acquired by young Saudis through education and the skills needed in the labor market (Harvard Kennedy School, 2015). Saudi students have been choosing college majors that are not in high demand in the labor market. This mismatch stems from the lack of up to date information about the skills required by the private sector which in turn fails to guide the educational choices of young Saudis. Saudi college students continue to prefer fields of studies that have poor job prospects, fields such as education and humanities. This causes market failure where private firms can’t find qualified Saudi workers and the latter can’t provide their labor services to the market. The suboptimal human capital investment decisions made by young Saudis will continue unless they get access to quality information about job opportunities and career choices. The Saudi’s Technical and Vocational Training Corporation (TVTC) is working on bridging the gap between acquired skills and required skills to help steer students toward the most promising college majors and vocational opportunities. TVTC provides direct job training programs through the College of Excellence (CoE). Other programs such as the Career Education Development (CED) program are designed to improved young Saudis access to career information. The goal should be to reach young Saudis with information campaigns on career availabilities and the appropriate fields of studies earlier in their education trajectory, starting for instance in middle school and continue until their last year of high school. The ongoing information campaigns should help guide young Saudis in making important decisions about their college education. Career fair and school career day are the best forms of info campaigns that have been used successfully in United States of America. The third stumbling block to Saudization is the lack of strategy and planning from both the Saudi government and the private sector. From his field work Fakeeh (2009) concluded that, the private sector in Saudi Arabia had been complaining that Saudization laws and methods seem to have been created on an ad hoc basis, using a trial and error system that changed as the program progressed. In addition, the Saudization program was established before the establishment of the infrastructure necessary for its implementation. Furthermore, 6 Proceedings of Annual South Africa Business Research Conference 11 - 12 January 2016, Taj Hotel, Cape Town, South Africa, ISBN: 978-1-922069-95-5 Saudization sets generalized quotas that are unrealistic, bans visas for jobs where there are not enough qualified Saudis to fulfill them, and restrict jobs to Saudis that they are not interested in occupying due to social reasons or unfavorable work conditions. The lack of strategic planning on the private sector side resulted from the belief that the Saudi government will delay executing the Saudization program. Private firms believed that the MoL will find other ways of employing the unemployed Saudis rather than looking at Saudization as the way of the future for the labor market. The following is a quote from a private businessman concerning his lack of strategic planning about the Saudization program (Fakeeh, 2009, p. 122): “Saudization is a national program. It deals with humans, the economy, and the whole society. Yes, we knew it was coming, but it was like a rumor or the flu that comes and goes seasonally.”[An elderly national businessman in electric appliances retail] Finally, the fourth major hurdle to the Saudization program is the costs resulting from its implementation. The private sector believes that it would be economically costly, especially in productivity, to force private companies to replace their hard working, experienced, and cheap foreign labor with inexperienced Saudis who often are under qualified and lack proper work ethics. In addition, the payroll budget of private companies would have to rise tremendously when nationalizing their work force because Saudi workers cost more in wages and salaries compared to their foreign counterparts. For companies that have resorted in hiring two Saudis for the job of one person to counteract low productivity, absences, and high turnover of Saudi workforce, the costs will be even higher (Fakeeh, 2009). Private companies face additional costs for training Saudis in order to provide them, for instance, with the IT skills and English business terminologies that are needed for a successful on the job performance. This is even more costly when the trainee drop out in the middle of the training program as it is often the case. The good news is that the Saudi Human Resources Development Fund (HRDF) provides companies with financial help to cover part of the costs of training Saudis but only for those who complete the program. Some of the private companies find the process just too complicated and choose not to ask for HRDF help (Fakeeh, 2009). 3.1.2. Saudi Workers’ Perspectives It will be remiss not to mention the Saudi workers’ perspective on Saudization since they are one of the major stakeholders of this program. According to Fakeeh (2009), economic expectations, educational factors, social constraints, career planning, and work circumstances are what Saudi workers consider to be the impediments to their successful participation in the Saudization program. The economic pressure for young Saudi graduates comes from the high cost of living, the dependency ratio per person, and a very low participation rate of women in the economy. Economically and socially, young Saudi men are expected to be the breadwinner of their 7 Proceedings of Annual South Africa Business Research Conference 11 - 12 January 2016, Taj Hotel, Cape Town, South Africa, ISBN: 978-1-922069-95-5 own family as well as helping their aging parents and many siblings financially. These expectations add an additional layer of challenge to new graduates, make it much harder for them to adjust to the work environment, and cause them to change jobs often looking for better paying ones. The constant moves from job to job deprive them of the benefit of building experience and the adjustment to work environment that they tremendously need (Fakeeh, 2009). The lack of educational background is mostly a hindrance for young unemployed Saudis with a high school diploma and college graduates with degree in fields that are not in high demand in the Saudi labor market such as libraries and archive, Islamic law, and Arabic language. Most unemployed Saudi high school graduates struggle to find jobs due to lack of IT and communication skills, lack of command of the English language, lack of problem solving skills, and undesirable professional conduct (Fakeeh, 2009). It is very frustrating for a young Saudi to realize that the Saudi educational system didn’t provide him with the basic skills that the labor market dim necessary for employment as stated in the following quote (Fakeeh, 2009, p. 151): “They ask me how good my English is. I tell them, as good as they taught me in the school. You can’t expect me to speak English like the Filipino or the Indian; it is fed to them since childhood. Ask anyone, we learn English ABC at 14 by a Saudi teacher who translates the lesson into Arabic. [Saudi errand messenger, industry and retail organization, Jeddah] Finally, young Saudis feel that the workplace ambience, work requirements, and pay structure are more suitable for foreign workers than nationals (Fakeeh, 2009). A requirement such as working long hours without proper financial compensation is not acceptable to a Saudi but it is to an expatriate, so they refuse to comply. In addition, Saudis are not satisfied with the pay system that pays a wage that is not sufficient to support a large family or to compensate for inflation. They believe that Saudi Arabian inflation is not a concern for most foreign workers whom they are expected to replace because these expats leave alone in the Kingdom and most of their expenses happen in their home countries where their families reside. Moreover, the lower wage that the expats receive in Saudi Arabia is more than enough for their families to have a decent life in their homeland in addition to covering their own expenses while living in Kingdom. The following quotes illustrate the feeling of a Saudi worker when it comes to the pay structure (Fakeeh, 2009, P. 153): “Be logical, he, the Filipino accountant clerk, can live as a rich man back in Manila on 700 dollars a month. He lives and eats in the company’s compound for nothing. Translated in Riyals it is 2600, just a bit more than my rent and we haven’t started with expenses, the wife’s needs and the car instalments. Can we both live the same life on the same pay? [Saudi accountant trainee, marketing organization] Some unemployed Saudis and those new to a job describe the work ambience as more tailored to the ways of the expatriate and cause them to feel uncomfortable in the workplace. The superiority that a supervisor holds over its subordinates in setting policies and in communicating with them is portrayed as demeaning and impossible for a Saudi to accept since it affects his image and pride (Fakeeh, 2009). 8 Proceedings of Annual South Africa Business Research Conference 11 - 12 January 2016, Taj Hotel, Cape Town, South Africa, ISBN: 978-1-922069-95-5 Overall, Saudi workers complain that as newcomers to the organization, they feel undermined and isolated by their foreign counterparts. They also believe that foreign workers don’t trust their ability to learn, so they intentionally delay the training and interfere negatively with the learning process. They feel that, during the training, their foreign counterparts in fear of being replaced by the Saudis; are willingly withholding information that might lead them to acquire the required skills faster and perform better quicker. One Saudi worker puts it this way (Fakeeh, 2009; p. 159): “For example, when I ask how are you going to charge this patient? What’s the method? They would say later, later. Oh, it’s okay. It’s easy. We will tell you later. I would ask, how do I channel this patient? Is there a special treatment for his being a VIP or an insurance patient? She would not give me the information I need. [Saudi administrative trainee, private health care, Jeddah] Only a few interviewed unemployed Saudis (two out of ten) blame their own attitude and lack of skills for their unemployment (Fakeeh, 2009). These Saudis feel unprepared and intimidated to replace the expatriates in a modern work environment. In addition, they claim that their inability to work long hours and not have time off for social and family matters work against them when compared to foreign employees who don’t have such obligations. Most Saudis also mentioned that social constraints do not allow them to fill many of the potential jobs that Saudization made available to them. Indeed, they will not accept certain types of occupations or categories of jobs, such as manual and technical work and some service-oriented jobs due to social considerations (Fakeeh, 2009). These types of occupations are deemed inferior by Saudis compared to a lower paying office job in an air conditioned building with a desk and a chair. Many young unemployed Saudis will not train or take these manual and technical jobs. IV. THE NITAQAT PROGRAM Due to the continuing failure of the Saudization program in reducing the number of unemployed Saudi nationals, the MOL decided in June 2011 to introduce a new re-enforcing program called the Nitaqat. The “Nitaqat,” which stands for “bands” or “zones” in Arabic, is a program aims at increasing work opportunities for Saudi nationals in the private sector by following a different set of rules than Saudization. Under the Saudization program, all private companies, irrespective of their economic activity and size were required to have 30% of their workforce occupied by Saudi nationals. Unlike the one size fits all Saudization quota system, the Nitaqat program measures the nationalization performance of companies by calculating, over successive periods of 13 weeks, a moving average of the percentage of Saudi nationals employed by a firm, taking into account the firm’s economic activity and size (Ministry of labor, 2011). Saudi nationals counted as employed in the quota measurement are those registered with the Central Department of Statistics and Information (CDSI). Based on the measured nationalization performance, companies are grouped into four bands: Excellent (Premium), Green, Yellow, and Red. The description of each band is presented in Table 2 below. 9 Proceedings of Annual South Africa Business Research Conference 11 - 12 January 2016, Taj Hotel, Cape Town, South Africa, ISBN: 978-1-922069-95-5 Table 2 Nitaqat Companies’ Classification Excellent/Premium Green Entities achieving superior nationalization performance with the highest percentage of Saudi employees Yellow Entities achieving good nationalization performance, with good percentage of Saudi employees Red Entities achieving below average performance with lower percentage of Saudi employees Entities achieving poor nationalization performance by hiring the lowest percentage of Saudi employees. These firms should represent no more than the bottom one fifth percentile of entities with same size and economic activity Source: Saudi Ministry of Labor, 2011; Saudi Hollandi Capital, 2012. The government of Saudi Arabia expects to quickly replace foreign workers with Saudi nationals in the private sector using the Nitaqat quota-based program. Each of the four classification groups of the Nitaqat has nationalization quotas which vary according the economic activity and employment size of the firms. This led to the remapping of the labor market into 45 economic activities and the grouping of companies into five sizes according to the number of employed workers. A micro company is a business with a total of 1 to 9 workers, while a company that has between 10 to 49 employees is classified as small. Medium size companies are businesses with a workforce of between 50 to 499 employees, while large companies are businesses with a total of 500 to 2999 employees. Giant companies are those with 3,000 employees or more. Altogether, the MoL created 225 different nationalization quotas for companies of different sectors and sizes. However, since business entities categorized as “Micro” were exempt from the Nitaqat system at the initial stage of the program for fairness and protection, the total number of nationalization quotas decreased to 180. Micro firms are, however, required to employ a least one Saudi nationals in their companies. Table 3 below shows a sample of Nitaqat color band ranges for the education sector. The quota ranges are widespread across the four categories of education services. Table 3 Samples of Nitaqat Color Bands (Saudization Quotas) in Education Sector Sector Small Size 10-49 Employees Kindergartens, Institutes And Colleges Red 0-9% Yellow 10-33% Green 34-69% Excellent 70% above Medium Size 50-499 Employees Large Size Giant Size 500-2,999 Employees 3,000 & more Employees 0-11% 12-34% 35-69% 70% above 0-14% 15-34% 35-69% 70% above 0-14% 15-34% 35-69% 70% above 10 Proceedings of Annual South Africa Business Research Conference 11 - 12 January 2016, Taj Hotel, Cape Town, South Africa, ISBN: 978-1-922069-95-5 Source: Saudi Hollandi Bank, 2012. For instance, a medium size (50 – 499 workers) college with 20 Saudi workers and 80 foreign employees will be classified as Yellow with a Saudization rate of 20 percent. The Nitaqat program was implemented in phases from its inception in June 2011. During the first phase of the program, all private companies were asked to update information about their employee at the Ministry of Interior and the General Organization for Social Insurance (GOSI). The Saudi MoL used the information provided by these companies to calculate their initial nationalization levels. The implementation of the Nitaqat program started with the second phase of the program that began in September 11, 2011. During this phase, the MoL began implementing sanctions against companies in the lower bands (Yellow and Red) and incentives for companies in the higher bands (Premium and Green). Additional sanctions and incentives were added incrementally in November 2011 and in February 2012. Both sanctions and incentives of the Nitaqat program are designed in a way that should lead the program to reach its goal of having 50% of companies of the same sector and size in the Green and Premium bands. Table 4 gives a summary of the Nitaqat sanctions and incentives for companies by color band. 11 Proceedings of Annual South Africa Business Research Conference 11 - 12 January 2016, Taj Hotel, Cape Town, South Africa, ISBN: 978-1-922069-95-5 Color Band Red Yellow Table 4 Nitaqat Sanctions and Incentives for Companies by Color Band Sanctions - Not granted new work visas - Not allowed to renew existing work visas - Not allowed to transfer visa to other Jobs - Can’t hire foreign workers from other firms - Not allowed to open new facilities or branches - Their foreign employees are allowed to transfer jobs to companies in the Premium & Green bands without their consent. (In the past, expats were required to work for at least two years with their current employer before they could work for another one). - Not allowed to renew work visas of foreign employees who have been in the Kingdom for six years or more - Not allowed to transfer visa to other Jobs - Can’t hire foreign workers from other firms - Not allowed to open new facilities or branches - No new temporary or seasonal visas - Their foreign workers are allowed to transfer jobs to companies in the Premium and Green bands without their consent including those who want to continue working in Saudi Arabia beyond six years. Incentives None - Can renew work visas of their foreign employees who have been in the Kingdom for less than six years. - Entitle to one new visa for every two of its foreign workers leaving the country on a final exit visa 12 Proceedings of Annual South Africa Business Research Conference 11 - 12 January 2016, Taj Hotel, Cape Town, South Africa, ISBN: 978-1-922069-95-5 Green None - Can renew existing work visas - Can apply for new work visas every two months - Entitled to one new visa for every two foreign workers leaving the country on a final exit visa - Entitled to “Open profession visas,” that is, firms can change and update their foreign workers’ profession (job descriptions) as necessary (excluding job restricted to Saudis) - Can hire foreign workers from Red and yellow firms without the consent of their current employers - Entitled to a six-month grace period for the submission of the Certificate of Zakat and Income Tax. - Entitled to a six-month grace period in the renewal of their expired professional license, commercial registration, and all MoL documents. Color Band Premium Sanctions Incentives None - Entitled to unrestricted approval of new visas, that is, firms can hire anyone from any part of the world any time. - Entitled to one new visa for every two foreign employees leaving the country on a final exit visa - Can use electronic system to apply for work visas for any type of profession (except for jobs restricted to Saudis) - Able to renew existing visas for any employee within three months of their expiration. - Entitled to open profession visas. - Can hire foreign workers from Red and yellow firms without the consent of their current employers - Entitled to a six-month grace period for the submission of the Certificate of Zakat and Income Tax. - Entitled to a one year grace period in the renewal of their expired professional license, commercial registration, and all MoL documents. Source: Ministry of Labor, 2011; Saudi Hollandi Capital, 2012. 4.1. Jobs Restricted to Saudis 13 Proceedings of Annual South Africa Business Research Conference 11 - 12 January 2016, Taj Hotel, Cape Town, South Africa, ISBN: 978-1-922069-95-5 In 2013, the Saudi MoL decided to tighten labor market regulations by reserving 19 jobs categories exclusively for Saudi nationals (Sayel, 2013). These restricted jobs are listed in Table 5. As per the MoL, there will be no work permit renewal for expatriates currently occupying jobs that are reserved for Saudis. Table 5 The 19 job titles off-limit to expatriates Executive HR manager staff relations clerk hotel receptionist Broker HR manager recruitment clerk health receptionist key specialist labor affairs manager staff affairs clerk claims clerk customs broker staff relations manager attendance control clerk treasury secretary staff relations specialist receptionist (general) Female sales specialists Security Source: Sayel, 2013. Restricting some jobs to Saudis should help speed up the Saudization process in these job categories which is in line with the nationalization campaign and the objective of reducing the number of unemployed Saudis. Other job categories such as Physicians, engineers, nurses, educators, designers, administrators, and technicians, can be occupied by foreigners, as long as they are not part of the exclusive list. Other initiatives of MoL are the “Hafiz,” “Liqaat,” and “Taqat” programs also introduced in 2011 and are run in conjunction with Nitaqat. Hafiz is an unemployment benefits program that grants unemployed Saudi men and women an allowance of SAR 2,000 ($533) every month for up to one year (Al-Jassem, 2012). In addition, Hafiz provides Saudi jobseekers with training and helps them find jobs. The “Liqaat” program holds job fairs across Saudi Arabia for the purpose of facilitating job interviews between employers and Saudi job seekers. The “Taqat” (capability) program focusses on helping match unemployed Saudis with jobs in the private sector. 4.2. Nitaqat Outcomes From its inception in 2011 to 2014, the quota-based Nitaqat program has reached its goal of moving companies out of the unsafe zones (Red and Yellow bands) and increasing the number of Saudis employed in the private sector. Saudi Deputy Minister of Labor Ahmad Al-Humaidan pointed out that almost 86 percent of private firms and establishments were in the safe zones (Green and Platinum bands) of the Nitaqat Saudization program as of October 2014. This was a big achievement for the Nitaqat program because in 2011, at the start of its implementation, companies in the safe and unsafe zones were at 50 percent each (Saudi Gazette, 2014a). Another positive result of the Nitaqat is the large increase in the number of Saudi nationals employed in the private sector which rose by 83.6 percent between 2011 and 2014 as shown in Table 6. he Saudization rate in the private sector rose from 10.8 percent in 2011 to 15.5 percent in 2014, a 43.5 percent increase (SAMA 2013, 2015). Data in Table 7 and Figures 1 & 2 show that this is a modest increase when considering the higher number of 14 Proceedings of Annual South Africa Business Research Conference 11 - 12 January 2016, Taj Hotel, Cape Town, South Africa, ISBN: 978-1-922069-95-5 jobs created in the private sector during those three years. Indeed, the private sector created about 2.2 million jobs (90.2 percent of total jobs created) between 2011 and 2014, however, only about 31.5% of these jobs (0.7 million jobs) went to Saudis and the remaining 68.5 percent went to foreign workers. Table 6 Private Sector Employment by Nationality, 2011 and 2014 Year Saudis (Million) Non-Saudis (Million) Total (Million) Saudization Rate (% ) 2011 2014 Percentage Change (%) 0.844 1.550 83.6 6.937 8.471 22.1 7.781 10.021 28.8 10.8 15.5 43.5 Source: SAMA 2014, 2015. Percentage changes calculated by the author Table 7 Job creation in the private and public sector, 2011-2014. Saudis Total Employment Private Sector NonTotal Saudis 6,937,020 7,781,496 Total Employment Public Sector Saudis NonTotal Saudis 919,108 79,030 998,138 Total Employment 8,779,634 2011 844,476 2014 1,549,975 8,471,364 10,021,339 1,168,586 72,162 1,240,748 11,262,087 Net increase-New Jobs created Jobs created as share of total (%) Allocation of new jobs (%) 705,499 1,534,344 2,239,843 249,478 (6,868) 242,610 2,482,453 9.8% 100% 90.2% 31.5% 68.5% 100% 102.8% (2.8%) 100% Source: SAMA 2013, 2015. Percentages measured by the author. 15 Proceedings of Annual South Africa Business Research Conference 11 - 12 January 2016, Taj Hotel, Cape Town, South Africa, ISBN: 978-1-922069-95-5 Figure 1. Share of Job creation by Sector, 2011-2014 Figure 2. Distribution of Newly created Private Sector 's Jobs by Nationality, 2011-2014 Public Sector 9.8% Private Sector 90.2% Source: SAMA 2013, 2015 Figure 3. Distribution of Newly created Public Sector Jobs by Nationality, 20112014 NonSaudis 0% Saudis 31.5% NonSaudis 68.5% Source: SAMA 2013, 2015 Saudis 100% Source: SAMA 2013, 2015 The public sector is the sector that employs the highest number of Saudis but creates fewer jobs as pointed out in Figure 2 above. The public sector created about 242,610 jobs (9.8% of total jobs created) between 2011 and 2014 and all of them were allocated to Saudis in addition to 6,868 public jobs that used to be occupied by expatriates. The Saudi labor market, thus, continues to be dominated by foreign workers who represented 8.5 million (75.2 percent) of a total of 11.3 million people working in the Kingdom in 2014 (SAMA, 2015). Did the Nitaqat program help the MOEP reach the targets set for the Saudi labor market in the ninth DP? Table 8 gives a summary of changes that occur in the Saudi labor market during the ninth DP in comparison to the set targets. According to the MOEP, the overall Saudization rate in 2014 stood at 44.5 percent (Jadwa Investment, 2015). This was a 7.1 percent decrease from its 2009 level, while the expectation was for the rate to rise by 11.9 percent. The Saudization rate was, thus, off target by 159.7 percent during the ninth DP. In addition, there was no big improvement in Saudis’ unemployment rate during the ninth DP despite the significant rise in the number of Saudi nationals employed in the private sector after the introduction of the Nitaqat program. Table 8 shows that Saudis’ unemployment rate rose from 9.6 percent in 2009 to about 11.7 percent at the end of the ninth DP in 2014, missing its target by 151.3 percent. Figure 4 demonstrates the increasing trend in the unemployment rates of Saudis nationals when compared to that of expatriates between 2008 and 2014. Saudis’ unemployment rate, which has been higher than that of expatriates, rose from 10 percent in 2008 to reach 12.4 percent in 2011, but declined modestly afterward with the implementation of the Nitaqat program. The higher level of Saudis’ unemployment rate, even after the implementation of the Nitaqat quota system, is not due to lack of jobs but to the faster growth in Saudi manpower and higher allocation of newly created private sector jobs to expatriates. 16 Proceedings of Annual South Africa Business Research Conference 11 - 12 January 2016, Taj Hotel, Cape Town, South Africa, ISBN: 978-1-922069-95-5 Table 8 Saudi Arabia Main Labor Market Indicators of at the End of the Ninth DP Percent Change during 9th DP Target Actual Percentage(1) Above & Off Target Actual 2009 Target 2014 Actual 2014 Saudi Manpower (000) Total Employment (000)(2) Saudi Non-Saudi Saudization Rate (Saudi Employment as % of Total) Unemployed Saudis (000) 4329.0 8173.1 3914.6 4258.5 47.9 5,328.6 9,396.3 5,037.0 4,359.3 53.6 5,577 11,068 4,927 6,141 44.5 23.1 15.0 28.7 2.4 11.9 28.8 35.4 25.9 44.2 -7.1 24.7 136 (9.8) 1741.7 (159.7) 414.4 291.6 651 -29.6 57.1 (292.9) Saudi Unemployment Rate (% of Saudi Manpower) 9.6 5.5 11.7 -42.7 21.9 (151.3) Source: Data from Ministry of Economy and Planning 2010a, 2010b, and 2010c and Jadwa Investment, 2015. (1) Positive numbers mean percentages above targets & negative numbers in parenthesis mean percentages off targets (2) Data from the Ministry of Economy and Planning are slightly different from data from Saudi Arabian Monetary Authority Percentage changes and percentage above & off target calculated by the author. Unemployment Rate by Nationality, 2008 – 2014 Figure 4 14.0 12.0 11.5 10.0 12.4 12.1 12.0 11.7 10.5 10.0 8.0 Saudis' Unemployment Rate (%) 6.0 Non-Saudis' Unemployment Rate (%) 4.0 2.0 0.5 0.3 0.4 0.4 0.1 0.4 0.7 0.0 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 2013 2014 Year Data Source: SAMA 2013, 2015 and Jadwa Investment, 2015. It is clear from Table 8 that the quantity of Saudi manpower sharply increased during the ninth DP, rising above target by 24.7 percent, while the number of employed Saudis rose but by a lower percentage than expected and was off target by 9.8 percent. Meanwhile, the number of employed expatriates in the Kingdom rose by 44.1 percent during the ninth DP, exceeding target by 1,742.7%. The Nitaqat incentive system is partially to blame for the inadequate employment number for Saudis in the private sector. Indeed, the current Nitaqat’s incentives available to private companies in the Green and Premium bands facilitate their hiring of more foreign labor. These companies are being granted new work visas as reward for being in the safe zones and they can hire foreign workers from unsafe zones without their employers’ consent. This increases the capability of firms in the safe zones to hire even more foreign workers as long as they remain within the quota. The Nitaqat’s incentive system, thus, seems to be contradictory to the goal of Saudization and will eventually have to be amended if visible changes in the Saudization rate are to occur. 17 Proceedings of Annual South Africa Business Research Conference 11 - 12 January 2016, Taj Hotel, Cape Town, South Africa, ISBN: 978-1-922069-95-5 Another reason for more hiring of expatriates in the private sector is the fact that most Saudis wouldn’t want to occupy jobs made available by the private sector that they deem inferior for cultural reasons. Better be unemployed than be caught doing one of those jobs. Consequently, the private sector will continue to need foreign workers for jobs rejected by Saudis. Most Saudis prefer to work for the government but there are not enough public jobs to accommodate all of them. Saudis preference of public jobs over private ones stems from the belief that private companies provide poor working conditions and low job security than the government (Harvard Kennedy School, 2015). Overall, the Nitaqat quota system was neither able to curb the level of unemployment for Saudis nor speed up the overall Saudization process during the past three year of its existence. Saudis’ unemployment rate only fell from 12.4 percent in 2011 to about 11.7 percent at the end of the ninth DP in 2014. The Saudization rate stood at 15.5 percent in the private sector and at 94.2 percent in the public sector in 2014 as shown in Figures 5 and 6 (SAMA, 2015). Figure 5. Share of Private Sector Employment by Nationality, 2014 Saudis 15.5% NonSaudis 84.5% Source: SAMA, 2015 Figure 6. Share of Public Sector Employment by Nationality, 2014 NonSaudis 5.8% Saudis 94.2% Source : SAMA, 2015 The overall Saudization rate, which was around 41.7 percent in 2011, rose but moderately after the start of the Nitaqat program, to reach 44.5 percent in 2014 (Jadwa Investment, 2015). Figure7 shows how the large number of expatriates employed in the private sector continues to growth even after the establishment of the Nitaqat quota system. The Saudization pace in the Kingdom would only speed up when the private sector will start to allocate more jobs (new and old) to Saudis. This might be possible after the introduction of the third phase of the Nitaqat program. The latter was supposed to be introduced on April 20, 2015 but was postpone until latter to allow the private sector more time to understand the standards of this phase. The Council of Saudi Chambers (CSC) put pressure on MoL to postpone the third phase of the Nitaqat for three years to avoid labor shortage in some sectors of the economy (Naffee, 2015). 18 Proceedings of Annual South Africa Business Research Conference 11 - 12 January 2016, Taj Hotel, Cape Town, South Africa, ISBN: 978-1-922069-95-5 Figure 7: Private Sector Employment by Nationality 12 8.21 8.47 10 8 6.21 6.27 6.91 7.35 6 Saudis (Million) 4 2 Non-Saudis (Million) 1.13 1.47 1.55 0.68 0.72 0.84 0 2009 2010 2011 2012 2013 2014 Data Source: SAMA 2012, 2013, 2015 The third phase of the Nitaqat program will raise the minimum Green zone’s Saudization requirements for several sectors, implement new calculation methods for the quota, and change the incentives system. The sectors that will be the most affected by changes in Green zone’s minimum Saudization requirements will be manufacturing, construction, financial, retail, and wholesale. The previous minimum Saudization requirement of 28 percent for retail and wholesale companies in the Green zone will rise to 32 percent. For large commercial establishments, the Green zone minimum Saudization rate will more than double going from 29 percent to 66 percent, while that for big firms will rise from 25 percent to 41 percent (SICO, 2015). Raising the Saudization rates at the current moment would negatively impact the labor market as Small and Medium Enterprises (SMEs) in sectors such as manufacturing, sales, and construction would not be able to recruit enough Saudi workers said the CSC (Naffee,2015) The start of the third phase of the Nitaqat will also bring a new calculation of Saudization rate for private sector companies that will be based on a moving average of the number of Saudi employees over successive periods of 26 weeks after being registered with GOSI rather than the current 13 weeks (SICO, 2015). Finally, the changes in incentives during the third phase will affect mostly companies ranked in the low Green zone, while changes in penalties will mostly impact companies in the Red and Yellow zones. Companies in low Green zone will no longer be granted new workers’ visas nor will they have permission to move employees around by changing their profession. Companies in the Red zone will have their licenses revoked while those in the Yellow zone will have their license suspended (SICO, 2015). 4.3. Nitaqat Shortcomings Some of the Nitaqat shortcomings include increase in private sector’s operating costs, increase in private business closures, and increase in ghost Saudization. Increase in 19 Proceedings of Annual South Africa Business Research Conference 11 - 12 January 2016, Taj Hotel, Cape Town, South Africa, ISBN: 978-1-922069-95-5 operating costs for private businesses are mainly due to the costs of training of Saudi employees and the higher wages they received compared to the wages of foreign workers. Yosef Al Zanbagi, HR manager of MICE Arabia Group for Exhibitions and Conferences, said that the royal order has made it mandatory for Saudis to be hired for management positions. He, then, added that training is important for Saudi employees hired in these positions in addition to their educational qualification. He believes that at least three months of on-thejob training are needed, including training for English, IT knowledge, Human Resources, and management training sessions (Khan, 2013). The higher costs of operation for private companies come from a higher minimum wage for Saudi employees, currently set at SAR3000 (Al-Jassem, 2012). The minimum wage for Saudi workers is expected to increase to SR5300 ($1,412) during the third phase of the Nitaqat program while that for foreign workers will be set at SAR2500. The rise in minimum wage would result in higher costs for companies in sectors such as retail, construction, and wholesale where the current average wage for Saudis is below SR5000 (SICO, 2015). The Deputy Labor Minister Ahmad Al-Humaidans said that “The challenges are setting a minimum wage commensurate with the needs of Saudi employees, as well as increasing the level of competiveness between the Saudis and expatriates,” (Arab News, 2014a). He also added that Saudi HRDF is currently providing financial support to private companies for payment of Saudi salaries up to 50 percent for two years. In addition, companies in the Green and Premium zones can benefit from this salary support for up to three or four years. However, this is a temporary solution that is only delaying the inevitable. The increase in the operating costs from the Nitaqat nationalization scheme and Saudi nationals’ reluctance to take up certain types of jobs had made it more difficult for companies to comply with the Saudization quota, resulting in a number of companies closing doors. For instance, more than 130,000 Saudi contractors were forced to close down in 2015 citing Saudization quotas under the Nitaqat as the root cause of their demise (Bhatia, 2015). In addition, statistics released by the MoL showed that 200,118 private sector companies (11.1 percent) out of 1.8 million companies in the Red zone of the Nitaqat program closed doors in 2013 (Arab News, 2014b). Furthermore, of all the firms that shut down in 2013, 58.6 percent of them were micro and small enterprises which are known to be in the White zone and exempt from the Nitaqat quota system but are required to employ at least one Saudi national. The rest of the firms that shut down were from the 255,833 private companies with 10 or more employees. More than 500,000 expatriates were employed by firms in the Yellow and Red Zones in 2013 (Arab News, 2014b). Finally, with the enforcement of the Nitaqat, some firms in the red and yellow bands illegally increased the number of their Saudis employees through “Ghost Saudization” so they can move to the Green band and avoid Nitaqat’s penalties. “Ghost Saudization,” means the registering of fake Saudi employees as employees of the company in order for the company to boost its Saudization quota. Ghost or fake Saudization has been used by private companies to circumvent the Nitaqat quota system and stay away from unsafe zones. “Ghost workers” are not required to go to work but receive a small monthly compensation for their services. 20 Proceedings of Annual South Africa Business Research Conference 11 - 12 January 2016, Taj Hotel, Cape Town, South Africa, ISBN: 978-1-922069-95-5 The phenomenon of Ghost Saudization has been exacerbated by the Nitaqat quota system. For instance, it was reported in Saudi Gazette that in early 2014, 30 schools were involved in the practice of ghost Saudization. They fake their Saudization figures by hiring over 2,000 ghost teachers. The schools signed contracts with the Saudi teachers who were not actually working for them (Saudi Gazette, 2014b). Moreover, in 2015, 18,000 women were found to be registered as ghost workers in several private companies and were paid around SAR500 to SAR1000 to be counted as employees. These women confessed to their crime, when they were caught while applying for social insurance with GOSI saying that they needed social insurance because their employment was fake Saudization (Saudi Gazette, 2015). In 2014, the MOL warned companies that if they engage in the hiring of ghost workers, they would be subject to punishment such as heavy financial penalties, the slashing of all services from the HRDF, and no hiring of new staff. Any company found guilty of hiring ghost workers will be asked to pay between SAR3,000 to SAR10,000 in fine. While any Saudi who agrees to be registered as ghost worker by a company or an institution will be denied support for a period of three years for the first offense and five years for the second (Naffee, 2015). It is worth noting that any established system of rules and regulations is always subject to loopholes, evasion, and corruption and the Nitaqat is not immune to it. The Nitaqat quota system has had its share of loopholes. For instance, private companies have used loopholes to cut the number of employees to nine or less in order to move to the White zone that is exempt from Nitaqat’s Saudization quotas. Some firms have paid bribes through ghost Saudization to increase the number of Saudis listed as employees of the company and evade the Nitaqat’s penalties. Unemployed Saudis accepted bribes so private firms can list them listed as fake employees of the company. The Nitaqat, thus, requires higher level of monitoring capabilities to prevent companies and individuals from defrauding it. The MOL has decided to establish a new controlling body for labor inspections that is expected to significantly increase its capabilities in monitoring and evaluating private companies. V. CONCLUSION The Nitaqat, as a re-enforcement program for Saudization, has had some level of success in meeting its goals but at significant costs to the labor market and the economy in the form of private companies’ closures. Nitaqat has led to the abandonment of the previous blanket quota of Saudization and to a better measurement of Saudization rate. In addition, more Saudis are now employed in the private sector as a result of Nitaqat and more companies have moved to the safe zones of the program. However, over 200,000 companies shut down two years after the introduction of the Nitaqat in 2011. These private companies couldn’t afford to hire enough Saudi employees to stay in the safe zones. So far, the Nitaqat program has not been able to put a dent on the unemployment rate of Saudis. Higher percentage of jobs created in the private sector is still being allocated to expatriates. The implementation of the third phase of the Nitaqat program might bring the much needed reform to the quota system. This phase of the program will initiate changes 21 Proceedings of Annual South Africa Business Research Conference 11 - 12 January 2016, Taj Hotel, Cape Town, South Africa, ISBN: 978-1-922069-95-5 such as increase in the minimum Saudization rate for some of the industries in the private sector, a better measurement of the labor quota, and improvement in the penalties and incentives’ system. Changes in culture concerning some jobs are also needed for young unemployed Saudis to consider occupying jobs that were considered as inferior in the past. Information campaigns should be used to help counteract the stigma about these jobs. Otherwise, there will be jobs available but nobody to occupy them as companies are squeezed even more in the number of expatriates they can hire. It is, therefore, paramount that the MoL considers the reality of the Saudi labor market and the state of the Saudi economy in its formulation of any new Saudization reform policies. There must be a synergy between labor policies and macroeconomic policies, otherwise, the opposite result could be attained and the economy will suffer for it. 22 Proceedings of Annual South Africa Business Research Conference 11 - 12 January 2016, Taj Hotel, Cape Town, South Africa, ISBN: 978-1-922069-95-5 References Al-Asmari, M.G.H., 2008. ‘Saudi Labor Force: Challenges and Ambitions,’ JKAU: Arts & Humanities, Vol. 16 No. 2, pp. 19-59. Al-Jassem, Diana, 2012. ‘Hafiz: Inspiration for Job Seekers,’ Arab News, 16 May 2012, Jeddah. Available at http://www.arabnews.com/saudi-arabia/hafiz-inspiration-job-seekers (Accessed September, 2015). Arab News, 2014a. ‘Jobs for Saudis: Nitaqat Rules tightened,’ 2 September 2014, Jeddah. Available at www.arabnews.com/news/623996 (Accessed September , 2015). Arab News, 2014b. ‘200,000 Nitaqat-hit-firms close down,’ 13 September 2014, Jeddah. Available at www.arabnews.com/saudi-arabia/news/629451 (Accessed September , 2015). Al-Shabrawi, Adnan (2015) ’18,000 Fake Saudization Cases Dropped from Social Insurance,’ Saudi Gazette, 13 July 2015, Riyadh. Available at http://saudigazette.com.sa/index.cfm?method=home.regcon&contentid=00000000250204 (Accessed November, 2015). Bhatia, Neha, 2015. ‘Private sector woes drive Nitaqat review in Saudi,’ Arabian Industry, 15 June 2015. Available at www.arabianindustry.com/constructio/news/2015/jun/15/private-sectorwoes-drive-nitaqat-review-in-saudi-5069571/#.vj80L9lrLcu (Accessed November, 2015). Chin, A. & Prakash, N., 2011. ‘The redistributive effects of political reservation for minorities: Evidence from India’, Journal of Development Economics 96(2), 265–277. Fakeeh, M. S., 2009. ‘Saudization as a Solution for Unemployment: The Case of Jeddah Western Region’ [online], Unpublished PhD thesis, University of Glasgow, Business School, Scotland, United Kingdom. Available at http://theses.gla.ac.uk/1454/1/Fakeeh_DBA.pdf (Accessed May, 2015). Harvard Kennedy School, 2015. ‘Back to Work in a New Economy: Background Paper on the Saudi Labor Market,’ Evidence for Policy Design, Harvard University, Boston, United States. Available at http://epod.cid.harvard.edu/files/epod/files/hks-mol_background_paper_-_full__april_2015.pdf Holzer, H. & Neumark, D., 2000. ‘Assessing affirmative action’, Journal of Economic Literature 38(3), 483–568. Howard, L. L. & Prakash, N., 2012. ‘Do employment quotas explain the occupational choices of disadvantaged minorities in india?’ International Review of Applied Economics 26(4), 489– 513. 23 Proceedings of Annual South Africa Business Research Conference 11 - 12 January 2016, Taj Hotel, Cape Town, South Africa, ISBN: 978-1-922069-95-5 Jadwa Investment (2015). ‘Saudi Labor Market Outlook: Current and Long-Term Challenges.’Available at www.jadwa.com/en/researchsection/research/economic-research (Accessed November 2015). Khan, Fouzia, 2013. ‘Saudis need Extra Training to Replace Expats,’ Available at www.arabnews.com/news/453731 (Accessed September, 2015). Looney, R., 2004. ‘Saudization and sound economic reforms: Are the two compatible?’, Strategic Insights 3(2), 1–9. Ministry of Economy and Planning, 2010a. Chapter 4-National Economy under the Ninth Development Plan, Ninth Development Plan, pp. 61-85, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, Available at http://www.mep.gov.sa/themes/Dashboard/index.jsp (Accessed April, 2015). Ministry of Economy and Planning, 2010b. Chapter 10-Manpower and the Labor Market, Ninth Development Plan, pp.169-188, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, Available at http://www.mep.gov.sa/themes/Dashboard/index.jsp (Accessed April, 2015). Ministry of Economy and Planning, 2010c. Brief Report on the Ninth Development Plan, 1431/321435/36 (2010-2014), Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, Available at https://chronicle.fanack.com/wpconten/uploads/sites/5/2014/archive.user_upload/Document en/Links/Saudi_Arabia/Report_Ninth_Development_Plan.pdf (Accessed April, 2015). Ministry of Economy and Planning, 2006a. Chapter Four-National Economy Under the Eighth Development Plan, Eighth Development, pp. 70-99, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, Available at http://www.mep.gov.sa/themes/Dashboard/index.jsp (Accessed April, 2015). Ministry of Economy and Planning, 2006b, Chapter Eighth-Manpower and Employment, Eighth Development Plan, pp. 155-178, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, Available at http://www.mep.gov.sa/themes/Dashboard/index.jsp (Accessed April, 2015). Ministry of Labor Saudi Arabia, 2011. Nitaqat Program [online], Available at http://www.emol.gov.sa/nitaqat/ (Accessed April, 2015). Naffee, Ibrahim, 2014. ‘Heavy Penalties for Hiring Female Ghost Workers,’ Arab News, 21 September 2014, Jeddah. Available at www.arabnews.com/Saudi-arabia/news/633201 (Accessed September, 2015). ______ ,2015. ‘Delay in Nitaqat’s Third Phase Cheers Expatriates.’ Arab News, 15 April 2015, Jeddah. Available at www.arabnews.com/news/732821 (Accessed September, 2015). Peck, Jennifer, 2014. ‘Can Hiring Contract Work? The Effect of the Nitaqat Program on the Saudi Private Sector’, Massachusetts Institute of Technology Working Paper. Retrieved from http://economics.mit.edu/files/9417 (Accessed, May 2015) 24 Proceedings of Annual South Africa Business Research Conference 11 - 12 January 2016, Taj Hotel, Cape Town, South Africa, ISBN: 978-1-922069-95-5 Prakash, N., 2009. Improving the labor market outcomes of minorities: The role of employment quota, IZA Discussion Papers 4386, Institute for the Study of Labor (IZA). Ramady, M., 2013. ‘Gulf unemployment and government policies: prospects for the Saudi labour quota or Nitaqat system’, International Journal Economics and Business Research X(Y). Randeree, K., 2012. Workforce nationalization in the Gulf Cooperation Council states, Occasional paper no. 9, Center for International and Regional Studies, Georgetown University School of Foreign Service in Qatar. Saudi Arabian Monetary Agency (SAMA), 2015. ’Fifty First Annual Report.’ Available at www.sama.gov.sa/enUS/EconomicReports/AnnualReport/5600_R_Annual_En_51_APX.pdf (Accessed September, 2015). Saudi Arabian Monetary Agency (SAMA), 2013. ’Forty Ninth Annual Report.’ Available at www.sama.gov.sa/enUS/EconomicReports/AnnualReport/5600_R_Annual_En_49_APX.pdf (Accessed September, 2015). Saudi Arabian Monetary Agency (SAMA), 2012. ’Forty Eight Annual Report: The Latest Economic Development.’ Available at www.sama.gov.sa/enUS/EconomicReports/AnnualReport/5600_R_Annual_En_48_APX.pdf (Accessed September, 2015). Saudi Arabian Monetary Agency (SAMA), 2011. ’Forty Seventh Annual Report.’ Available at www.sama.gov.sa/enUS/EconomicReports/AnnualReport/5600_R_Annual_En_47_APX.pdf (Accessed September, 2015). Saudi Hollandi Capital, 2012. Labor and Nitaqat Program: Effect on Saudi Arabian Economy [online], available at http://shc.com.sa/en/PDF/RESEARCH/Labor%20and%20The%20Nitaqat%20Program.pdf (Accessed May, 2015). Saudi Gazette, 2014a. ‘86% of companies in Nitaqat’s Safe Zone,’ 28 October 2014, Riyadh. Available at www.saudigazette.com.sa/index.cfm?method=home.regcon&contentid=20141029222697 (Accessed November, 2015). Saudi Gazette, 2014b. ’30 Schools fake Saudization Figures,’ 02 February 2014, Riyadh. Available at www.saudigazette.com.sa/index.cfm?method=home.regcon&contentid=20140208195080 (Accessed November, 2015). Sayel, Abdullah, 2013. ‘The 19 Exclusive Saudi Jobs,’ Arab News, 14 May 2013, Jeddah. Available at www.arabnews.com/news/451552 (Accessed September, 2015). 25 Proceedings of Annual South Africa Business Research Conference 11 - 12 January 2016, Taj Hotel, Cape Town, South Africa, ISBN: 978-1-922069-95-5 Sfakianakis, J., 2014. ‘Saudi Arabia’s Upcoming 10th Economic Development Plan is of Critical Importance’, Saudi-US Trade Group [online], Available at http://sustg.com/saudi-arabiasupcoming-10th-economic-development-plan-is-of-critical-importance/ (Accessed May, 2015) Saudi Arabian Monetary Agency (SAMA), 2015. ‘Fifty First Annual Report.’ Retrieved from www.sama.gov.sa/en-us/economicreports/annualreport/5600_R_Annual_En_51_apx.pdf (Accessed, October 2015) ______ ,2013. ‘Forty Ninth Annual Report: Latest Economic Development.’ Retrieved from www.sama.gov.sa/en-us/economicreports/annualreport/5600_R_Annual_En__apx.pdf (Accessed, October 2015) SICO Investment Bank, 2015. ‘GCC Economics: Impact of Nitaqat’s Third Phase on the Private Sector.’ Available at http://www.marketstoday.net/includes/download.php?file=rr_05032015171346.pdf&lang=en &s=1791&m=research (Accessed, November 20) 26