Proceedings of 3rd Global Business and Finance Research Conference

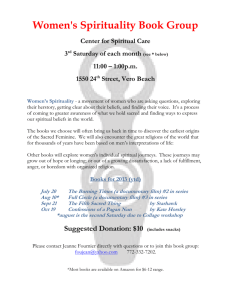

advertisement

Proceedings of 3rd Global Business and Finance Research Conference 9 - 10 October 2014, Howard Civil Service International House, Taipei, Taiwan ISBN: 978-1-922069-61-0 What ought to be: Modeling Culture-Based Managerial Leadership Yusuf Nur and Adam R. Smith Recently there has emerged burgeoning literature on Management by Virtues (MBV) and concepts closely related to it, penned by practitioners, academics and consultants. These authors refer to MBV by different names, such as servant leadership, spiritual leadership, stewardship, principle-centered leadership, management by values, service leadership, and other similar terms. Although the names used are different, they have many aspects in common, the main component of which is striving to run an organization and manage employees according to virtues derived from firm belief in the spiritual or the transcendental aspects of life. The following paragraphs will attempt to integrate and summarize several books and articles written on this topic. Perhaps the first practitioner to write about some aspects of MBV was Robert Greenleaf who worked for AT&T for decades before publishing his seminal work Servant Leadership in 1978. Greenleaf’s philosophy is based on the premise that an effective leader is a trustworthy servant, i.e., earns the trust of his/her followers by being their servant. A new moral principle is emerging which holds that the only authority deserving one’s allegiance is that which is freely and knowingly granted by the led to the leader in response to and in proportion to, the clearly evident servant stature of the leader. Those who choose to follow this principle will not casually accept the authority of existing institutions. Rather, they will freely respond only to individuals who are chosen as leaders because they are proven and trusted as servants. To the extent that this principle prevails in the future, the only truly viable institutions will be those that are predominantly servant-led. (p.10) Some of the qualities and attitudes that Greenleaf attributes to servant leaders include that they are adept listeners, excellent communicators, good empathizers, and are patient and determined. Furthermore, they possess an intuitively developed sense of direction and they highly value community. It is evident that the above qualities of servant leadership could be attributed to leaders who don’t claim to be servants. However, Greenleaf connects his servant leadership concept to spirituality. To him to be a servant leader, one has to be necessarily spiritual. Greenleaf defines spirituality as “the animating force that disposes one to be a servant of others” (Greenleaf, 1982, p. 4-5). For Greenleaf spirituality is not confined to religious institutions. In fact, according to him, a religious institution may not be spiritual at all if it doesn’t create a servant environment. On the other hand, a _________________ Assoc.Prof. Yusuf Nur, Email: ynur@iuk.edu School of Business, Indiana University Kokomo, United States, Proceedings of 3rd Global Business and Finance Research Conference 9 - 10 October 2014, Howard Civil Service International House, Taipei, Taiwan ISBN: 978-1-922069-61-0 business organization can create a spiritual environment if its leadership succeeds in becoming trustworthy servants to their followers. DePree (1989) emphasizes the importance of belief and spirituality for management practices implemented in the workplace. He argues that our management “style is merely a consequence of what we believe, of what is in our hearts” (p. 24). With admittedly unsupportable exaggeration DePree (1989) further writes, “Managers who have no belief but only understand methodology and quantification are modern day eunuchs. They can never engender competence or confidence. They can never be truly intimate” (p. 27). Another writer that considers spirituality as a necessary component of effective management and the vision that is so integral to it is Vail (1990), who contends that a truly energizing vision has to be necessarily centered in profound spirituality. For Vail, spirituality is “the search for deeper experience of the spirit of various kinds that one can feel stirring within... [which is the essence of] being human” (p. 213). Vail goes further by asserting that true leadership has to be necessarily spiritual since “true leadership brings out the best in people and since one’s best is tied intimately to one’s deepest sense of oneself, i.e. one’s spirit” (p. 224). Ritscher (1986) ascribes ten qualities to spiritual leadership: 1. inspired vision, 2. clarity of mind, 3. strong will, toughness, and good intention, 4. low ego, 5. no compartmentalization of life, 6. trust and openness, 7. clear insight into human nature, 8. skill in creating human structures (which he calls groundedness), 9. integrity, and 10. context of personal growth and fulfillment (p. 62). Ritscher states that all these qualities are transcendent in nature, i.e., “they go beyond the mundane and measurable effort in human experience and organizational dynamics.” One of the CEOs most successful in incorporating spirituality in business management is Chappell (1994) of Tom’s of Maine. Chappell (1994) considers managing his business according to values derived from spirituality his “call” in life. After founding and running a successful business, Tom Chappell realized that his apparent success didn’t make him happy. He attributed his unhappy state to the fact that he moved away from his spiritual values as his business became more successful. He felt empty and disconnected from himself; for him life lost its meaning. He lost his sense of purpose, a sense he knew he possessed before he and his company became successful. He set out on a quest to understand what made him lose his sense of purpose and meaning. This search for meaning and purpose in his life and business life led him to the Harvard Divinity School and to religion. He was not an irreligious person to start with, but he felt because of his material success he had drifted away from his core values. The one question he sought an answer for was “could I stick to my respect for humanity and nature and still make a successful company even more successful?” He came to the conclusion that one didn’t have to give up sound business practices for one’s values to guide every business transaction. He realized that when he and his wife founded Tom’s of Maine, they started right – their core values guided their decisions. As time went by and the company grew and became successful, they Proceedings of 3rd Global Business and Finance Research Conference 9 - 10 October 2014, Howard Civil Service International House, Taipei, Taiwan ISBN: 978-1-922069-61-0 “slipped” by becoming assimilated into the mainstream business practices where rational calculations and dry number crunching reigned supreme. He came to learn that life is a balancing act between the spiritual and the practical – that there is a middle way of making room for spirit in the world of commerce. This is how Chappell (1994) defines spirit or spiritual: By spirit or spiritual, I mean the part of you that survives when you eliminate your flesh and bones – the part you can’t point to but can feel, the part you might describe to someone else as your essential being, your soul. Soul is what connects you to everyone and everything else. It is the sum of all the choices you make. It is where your beliefs and values reside. Soul is at the center of our relationships to others, and for me it is at the center of the business enterprise. Like DePree (1989), Chappell came to the conclusion that beliefs drive strategy. Creating a spiritual climate allows workers to be fully engaged. In contrast, if the driving principle of the company is to maximize profit, workers will limit themselves to the bare minimum required of them. When workers are engaged fully, when they and their managers have common values and shared sense of purpose, their daily work would be imbued with deeper meaning, which leads to satisfaction and fulfillment. Chappell came up with a vision of working hard “to make good products for customers who care as much as we do about our health, the environment, and the future of our communities.” Some companies support community projects mainly for public relations purposes. Tom’s of Maine believes that doing good is an end in itself. The company can do good and profit at the same time; the two are not mutually exclusive. Chappell attributes his business philosophy to ideas he culled from a number of religious thinkers including Martin Buber, Immanuel Kant, and Jonathan Edwards, whose works he studied at the Harvard Divinity School. According to Chappell, our values are the driving force behind the decisions we make. In regular business situations, the right decision is the one that leads to the maximum profit. This attitude is called utilitarianism. In contrast to utilitarianism, formalism is the belief that making money is not the only goal of either business or work. Formalism has to do with “inner sense of obligation and human connection that people feel for their friends, neighbors, and family.” People are not motivated by mere material considerations. They could be motivated by respect for them exhibited by their bosses and co-workers Chappell derives his management philosophy from Martin Buber’s I and Thou. Buber divides relationships into two categories. In an “I-It” relationship people are treated like objects to be used to attain our goals. People are valued for their utility. In an “I-Thou” relationship, however, we relate to people not for anything in return but in simple respect, love, friendship, and honor for their own sake. According to Chappell most businesses are predicated on an “I-It” relationship. This is the standard way of doing business. According to Chappell, the natural outcome of doing business according to IThou principles is high morale, loyalty, commitment, and workers going beyond the call Proceedings of 3rd Global Business and Finance Research Conference 9 - 10 October 2014, Howard Civil Service International House, Taipei, Taiwan ISBN: 978-1-922069-61-0 of duty. Chappell maintains that business needs and spiritual needs can and should be balanced. When such a balance is attained management will be able to contribute to the spiritual growth of its workers. By fostering the quest for meaning of life that everybody feels, business will create meaning of work that is so necessary for the morale and motivation of the workers. On the other hand, if business confines itself to profit-making only, and neglects the spiritual side of business life, it will strip away a part of the worker that needs to thrive if they are to lead a healthy work life. This in turn will lead to listlessness and apathy on the part of worker. The driving concern for the worker will then be to do the minimum in order to please his/her boss. Another seminal work on MBV and spirituality in the workplace has been penned by Marcic. Marcic (1997) maintains that the world we live in obeys not only physical laws but also spiritual ones. These spiritual laws are taught by all traditional religions and are not confined to one specific religion. Marcic compares some of the basic teachings of all major religions and comes to the conclusion that they all emphasize love and service for others, honesty in dealings, justice for all, patience and tolerance, dealing with others with pure intentions, and avoidance of corrupt practices, among other teachings. According to Marcic, behaviors are the outer manifestation of attitudes, which are in turn based on deeply ingrained beliefs. These beliefs come from religious teachings on spirituality or spiritual laws. Spirituality addresses the world of spirit and the soul – a world unseen but as real as the physical world to those who believe. By following spiritual laws we develop virtues that help us deal properly with others. These spiritual laws are universal. For example, the golden rule is found in all religions, although it is expressed in different ways. Spiritual laws specify cause and effect in the same way that physical laws specify cause and effect. Breaking spiritual laws, whether we are aware of them or not, entails certain consequences. For example, practicing honesty leads to building trust. Likewise dishonest behavior destroys trust. The business world is not exempt from spiritual laws in the same way that it is not exempt from physical laws. Virtuous behavior results from following spiritual laws. For example following the Golden Rule in business entails that we would not intentionally hurt our subordinates, bosses or colleagues, that we would not treat them unjustly, and that we would not hurt their dignity or disrespect them because we would not want anybody to do these things to us. Marcic (1997) contends that one of the most important spiritual laws all religions teach is purity of intention or motive. This law teaches people to be sincere in what they do and how they deal with others – not to obtain anything specific in return, but to do it for its own sake. Spiritual managers don’t treat workers well in order to get them to produce more. They treat them well because they sincerely believe that treating others well is a virtue required by your beliefs. Because employees are affected not only by actions directed at them but also the motives behind those actions, when programs that are intended to make workers feel good but not bring about any substantive change are implemented, workers become cynical and disillusioned. Workers have countless ways of getting back at organizations that deal with them with insincerity. Workers can detect Proceedings of 3rd Global Business and Finance Research Conference 9 - 10 October 2014, Howard Civil Service International House, Taipei, Taiwan ISBN: 978-1-922069-61-0 whether proposed changes reflect core values of the organization as represented by its top managers or they are intended as a way to pay lip service to expectations. It is important to note here that spirituality is practiced as an end itself, and not as a means to an end. The overall attitude that spiritual managers are reputed to have is that the positive outcomes attributed to the practice of spirituality will take care of themselves. In other words, these outcomes are not to be sought in their own merit. Building on models developed by Vail (1989) and Hawley (1993), Marcic (1997) identifies five dimensions of work: physical, intellectual, emotional, volitional and spiritual. Most efforts at organizational design and improvement have been directed at the first two dimensions. To a lesser degree, the volitional (desire or will to change for the better) side of work is sometimes addressed. However, the emotional and the spiritual dimensions are in most cases ignored. Marcic believes that most changes instituted in organizations fail because they neglect the emotional and spiritual side of these changes. Toward a Definition of MBV From the above brief review of the literature, it is evident that MBV as a concept has an abstract dimension, which most of the literature calls spirituality, and a more practical dimension, which is related to virtuous behaviors resulting from spirituality. In the following paragraphs these two aspects of MBV and their relationship will be delineated. Marinoble (1990) conceives of spirituality as the central aspect of a person’s life orientation that involves finding and making sense of life’s significant questions, adhering to that meaning, and acting it out. Spirituality entails an openness to both rational and non-rational dimensions of reality that includes a striving for the transcendental, which Ritscher (1990) defines as “go[ing] beyond the mundane and measurable effort in human experience and organizational dynamics” (p. 62). Spirituality imparts to the one who practices it an inward reality, the outward manifestation of which could include the ability to touch people and to evoke a caring, creative, and ethical atmosphere in the workplace (Jacobsen, 1994). In other words, spiritual leaders are sensitive to issues of meaning, care, and wonder in the personal dimension, which allows them to be sensitive to these issues in their organizations. According to Jacobsen (1994), spiritual leaders can create an environment where “leaders and followers raise one another to higher levels of morality and motivation” (p. 95). According to Mitroff and Denton (1999), spirituality consists of deeply engrained beliefs, which by their very nature compel a person practicing it to be characterized by virtuous behaviors. The beliefs consist of belief in a deity, supreme power, or being that controls the universe. Integral to the belief in a deity is the belief that there is purpose behind creation, that the universe and life on earth are not meaningless. Proceedings of 3rd Global Business and Finance Research Conference 9 - 10 October 2014, Howard Civil Service International House, Taipei, Taiwan ISBN: 978-1-922069-61-0 Meaningfulness and purpose ascribed to life in general have important ramifications for meaning ascribed to work-life. Spirituality also entails belief in the interconnectedness of everything. A spiritual person deems it unnatural to compartmentalize one’s life (Ritscher, 1986). This feeling of being connected to others gives one a sense of community (Chappell, 1994). Spirituality requires faith and hopefulness, which eliminate fear and pessimism. Finally, spirituality fosters positive assumptions about human nature and human relationships. Human beings are treated as ends in themselves and not as means to an end. Human beings are to be treated with respect and accorded dignity, an inalienable right that comes with being a human being. Ashmos and Duchon (2000) define spirituality as “that dimension of human beings which is concerned with finding and expressing meaning and purpose and living in relation to others and to something bigger than oneself” (p. 131). Spirituality gives people who practice it a sense of purpose and meaning in their lives. It allows them to fully express their being, not only physically, but also mentally and emotionally. This quality of meaningfulness felt in one’s inner self leads to a more meaningful outer life and work-life. Managers who encourage their employees to actively practice spirituality also create an environment that fosters the development of this inner dimension. MBV managers recognize this need and know that the work environment can either nurture it or stifle it. A spiritually nurturing workplace would allow employees to fully apply themselves, which in turn has positive implications for the business. Ashmos and Duchon (2000) contend that the meaning sought in work and putatively provided in MBV organizations is different from the kind of meaning addressed by the job design literature, the emphasis of which is on finding meaning in the performance of tasks (Hackman & Oldham, 1975). Mitroff and Denton (1999) have carried out one of the few empirical studies on spirituality. Mitroff and Denton conducted more than 100 in-depth interviews with CEOs and senior managers. The subjects consisted of both supporters and opponents of the practice of spirituality in the workplace, the latter being managers who believe that spirituality is a private matter and there is no place for it a business organization. Among active supporters and promoters of the practice of spirituality, the most recurring notions associated with spirituality were the feeling of being connected with one’s complete (inner and outer) self, other human beings (especially those one closely associated with) and the entire universe. As Marcic (1997) theorized, Mitroff and Denton (1999) report that employees and managers who worked for organizations where the practice of spirituality was encouraged, claim that they could bring more of themselves to work and give more of themselves. In other words, MBV organizations are able to harness not only the physical, intellectual and emotional energies of its employees, but also their spiritual energies. MBV managers say that spirituality imparts a strong sense of purpose and direction, and it imbues life with meaningfulness – a purposefulness and meaningfulness derived from religious beliefs that teach that life is not just about making money, but about spreading and increasing goodness on earth. These beliefs also teach that work-life cannot be separated from life outside work. Proceedings of 3rd Global Business and Finance Research Conference 9 - 10 October 2014, Howard Civil Service International House, Taipei, Taiwan ISBN: 978-1-922069-61-0 From the above review, it can be concluded that MBV consists of the following dimensions: belief in a deity and the inner awareness that such a belief fosters, heightened consciousness of the meaningfulness and purposefulness of life, a strong feeling of community and connectedness, and an I-Thou attitude, which engenders faithfulness and sincerity in relationships. Theoretical Justifications for MBV The above review was mainly based on the spirituality literature, which usually does not appear in mainstream academic outlets. There are mainstream concepts, however, which lend much support to MBV. In the following section, some important concepts and themes that provide theoretical bases for MBV will be discussed. As will be shown, MBV has many aspects in common with concepts that have been around for a long time in the literature of organizational theory. Firmly Held Moral Values One of the most important contributions of Chester Barnard (1938) to organizational theory is his insistence on the importance of strongly held moral values to secure the willingness of the participants that organizations rely on. According to the author, material incentives to induce this willingness are necessary but not sufficient. The moral basis of cooperation may be even more important than any material incentives. This is absolutely necessary in order for the manager to secure, create and inspire morale in the participants. One of the most important functions of the executive is to gain the commitment of the participants to the common purpose of the organization. Although Barnard’s “moral imperialism” has come under scathing attacks (e.g., Perrow, 1986), his ideas formed the basis of neoclassical organizational analyses that emphasize the essential importance of strongly held moral values for the establishment of effective organizational cultures. Deontological Paradigm as an Alternative According to Etzioni (1988), the neoclassical economic paradigm, which views human beings as rational utility maximizers, pervades the analysis of not only economic relationships but also all other social relations. Etzioni proposes a different way of looking at ourselves as human beings. He calls his proposal a deontological paradigm. (A paradigm is a set of assumptions that provide an orderly way of organizing our thinking about a particular phenomenon.) This assumes that human beings have other goals besides maximizing their individual pleasures or interests. Today’s studies of societal relationships are based on this “utilitarian ethic.” A second aspect of this position is that it refutes that people seek the most efficient way to attain their goals. The deontological paradigm maintains that people choose means to their goals based on emotions and value judgments. Drawing on emotions and value judgments does not necessarily mean that people make poor choices. A third aspect of this new paradigm is that it views people as members of social collectives. People’s decisions are shaped by their social collectives. It is the social collective that determines feasible exchanges and markets within which these exchanges take place. Proceedings of 3rd Global Business and Finance Research Conference 9 - 10 October 2014, Howard Civil Service International House, Taipei, Taiwan ISBN: 978-1-922069-61-0 The new paradigm is based on three core assumptions, all of which are modifications of three core assumptions that are integral to the neoclassical paradigm. The first assumption is that people pursue not one but two “sources of valuation,” pleasure and morality (pp. 4-5). The second assumption is that decision-making (i.e., selection of choices) is done on the basis of values and emotions and not just on rational consideration, as the neoclassical paradigm holds. This decision-making framework holds in both social settings and economic settings, such as employeremployee relationships. Etzioni doesn’t deny that one can practice rational decision making, and critical thinking, even with reference to values and emotions that enter into the evaluation of alternative courses of action. The third assumption is that the decision-making unit is not just the individual but the individual within the collectives to which the individual belongs. According to Etzioni, the collectivities have their own structures, which constrain the individual decision maker. The individuals within the collectivities adhere to shared moral values that are internalized. When the neoclassical paradigm recognizes the existence of collectivities, it recognizes them as mere aggregates of individuals. Etzioni states that “individuals and community are both completely essential, and hence have the same fundamental standing. … [T]he individual and the community make each other and require each other” (p. 9). This does not negate the necessity of individual freedom or liberty. True individual liberty requires a community which ensures that individual liberty does not violate the order of that community. It is this balance of freedom and order that permits the ordering of preferences in the marketplace. Reversion to Pre-industrial Moral-Unity Shepard and colleagues (1996) concur with Etzioni’s (1988) analysis. According to the authors, Etzioni’s “new” paradigm is not really new. It is actually much older than the neoclassical paradigm it is supposed to augment. The norms and moral values championed by the new paradigm prevailed in the preindustrial economic and social situation in the West. In the preindustrial period, societies were characterized by “moral unity,” (i.e., “the same set of values, rules, norms, and customs applied to all groups, including business organizations”, pp. 580 –581). Only in the industrial period did this situation change to one, which exempted business relations from the moral constraints which applied to other social relationships. This was the essence of the amoral paradigm. According to Shepard and colleagues (1996), there are a number of clear indications that economic relationships in the United States are reverting to the preindustrial moral unity paradigm. First, the theoretical justifications for the amoral paradigm, which at one time appeared to be unassailable, are now being attacked by prominent social scientists, and by economists. Viewpoints attributed to Adam Smith, the father of laissez faire economics and its underlying neoclassical paradigm, have come under attack. It appears that Adam Smith was misinterpreted. According to Shepard and colleagues, Adam Smith never intended to separate morality from economics. Adam Smith’s pursuit of self-interest was not a goal in itself, but rather a means to attain the general welfare of the society. Second, numerous empirical studies have demonstrated that the one-sided view of human nature fostered by neoclassicism Proceedings of 3rd Global Business and Finance Research Conference 9 - 10 October 2014, Howard Civil Service International House, Taipei, Taiwan ISBN: 978-1-922069-61-0 is too simplistic to account for human economic decisions. The neoclassical paradigm does not have a place for economic decisions made on moral grounds. Another neoclassical position refuted by the above empirical studies is the atomistic separation of economic decisions from societal and cultural contexts within which they are made. The market does not operate independent of social considerations. Economist Lester Thurow (1984) rejects the basic assumptions underlying neoclassical theory of economic behaviors, specifically rational decision making based on utility maximization. A third reason why economic relationships are reverting back to the preindustrial moral unity paradigm is that a number of studies attribute contemporary economic prosperity of a number of countries to their communitarian cultures (Hofstede, 1991; HampdenTurner & Trompenaars, 1993). Among the countries with strong communitarian values and successful economies are Japan, Hong Kong, Singapore and Taiwan. Indeed Weber (1958) attributes the success of capitalism to the Protestant Ethic of Western Communities where it first took root. It is important to note, however, that there are many communitarian cultures around the world that are not associated with economic success. Agency Theory and Its Shortcomings One of the most influential management theories that is often used to explain and predict employee-employer behaviors in organizational settings is Agency Theory. Agency theory derives its impetus from assumptions about the nature of man underlying the neoclassical paradigm (see Eisenhardt (1989) for a review of Agency Theory). Recently a number of major criticisms has been lodged against Agency Theory (David et al., 1997; Hirsch et al., 1987; Perrow, 1986; Jensen & Meckling, 1994; Doucouliagos, 1994). Most of these criticisms revolve around the limited conceptualization of man, which Agency Theory borrowed from economics. Agency Theory assumes the existence of an agency problem arising from the rational, selfish, utility maximizing behaviors of those who are put in principal-agent situations. According to the theory, without bureaucratic controls, the agents will maximize their utility at the expense of the principals. Agency Theory is based on a narrow, oversimplified picture of human nature. Part of the reason Agency Theory resorts to such oversimplification is that it is hard to capture all the complexities of human nature and human economic behaviors in the mathematical models. Thus, Agency Theory and the assumptions it is based on overlook situations where human beings do not act in the prescribed fashion. Stewardship Theory as an Alternative Davis and colleagues (1997) and Donaldson (1990) proposed Stewardship Theory to rectify the limitations of Agency Theory. Stewardship Theory postulates that human beings do not always act individualistic or in a self-serving manner. When such situations arise, Agency Theory attributes them to irrationality on the part of the actors. As we have seen, Etzioni (1988) maintains that moral utility maximization does not entail irrationality. In stewardship theory, the so-called agent is not motivated by selfinterest but communatarian interests as well. In other words, according to Stewardship Theory, the interests of the organization as a collective are aligned with the interests of the individual. In such organizations, structures are created that empower people and that make them feel trusted, whereas organizations acting in accordance with Agency Proceedings of 3rd Global Business and Finance Research Conference 9 - 10 October 2014, Howard Civil Service International House, Taipei, Taiwan ISBN: 978-1-922069-61-0 Theory would resort to internal and external controls which lead to distrustful processes. Human behavior depends in large part on how humans are treated. Organizations that are designed along the lines of the neoclassical paradigm, therefore, introduce distrust into the work environment and create a self-fulfilling prophecy. Summary and Synthesis Barnard’s (1938) strongly held moral values as an imperative for organizational participation, Mitchell’s (1993) leadership legitimization through moral rectitude, Etzioni’s (1988) deontological alternative to neoclassical economic paradigm, and Shepard and colleagues’ (1996) moral-unity reversion claim, all support the contention that MBV rests on strong theoretical justification supported by existent mainstream organizational theory literature. Similarly, Stewardship Theory’s reliance on intrinsically motivated workforce, parallels the proposed style of management’s reliance on the development of the inner-self. Both base their contentions on the premise that the fulfillment of human beings higher order needs can be used to raise them to their full potential. This does not mean that MBV ignores extrinsic motivational tools. Whereas management theories based on economic assumptions use these rewards as tools of control, MBV relies on self-control and self-monitoring, both of which derive their impetus from moral values. MBV also ties to Hackman and Oldham’s (1975, 1976, 1980) work on motivation through work characteristics. Under MBV, workers experience intrinsic meaningfulness of work. They are respected as human beings and trusted, which in turn gives them strong feelings of responsibility. To create internal work motivation, Hackman and Oldham (1980) recommend increasing skill variety, task identity, task significance, autonomy, and feedback. Although these factors are important, not every job can be designed that way. The intrinsic motivation of MBV instead relies on infusing transcendental meaning to work – meaningfulness that is not contingent on the specificity of the work. Hackman and Oldham contend their redesign of work leads to highly motivated workers and good performance. MBV attains the same goal by tapping and unleashing the human spirit through transcendentally meaningful work. Employees in MBV situations develop a strong identity with the organization. The process of identification starts during recruitment. MBV managers screen potential employees for their acceptance of the organization’s mission, vision, and objectives. Thus, one can expect high identification with the organization on the part of these employees. Employees that strongly identify with the organization internalize the successes and failures of those organizations. If the organization succeeds, it is their mission that has succeed; and if the organization fails they take it personally. To them there is more at stake than their employment. There is a downside to selectivity, however. The strong values proposed above may in the long run trump technical competence, ability, and creativity as criteria for selection, attraction and retention of individuals. Proceedings of 3rd Global Business and Finance Research Conference 9 - 10 October 2014, Howard Civil Service International House, Taipei, Taiwan ISBN: 978-1-922069-61-0 Spirituality fulfills a number of innate needs human beings have. One of these is the need to relate to something bigger than oneself or the created things and beings that surround us. Another need is to seek meaning and purpose in life. Since work-life is such a huge part of our daily lives, an integral part of this need is to ascribe meaning and purpose to work-life. The practice of spirituality gives workers the opportunity to express aspects of their being other than the performance of physical or intellectual tasks. An integral part of belief in deity is a deep recognition of the spiritual dimension of human beings. Spirituality assumes that there is an inner part of human beings (called the soul, spirit or inner self), which needs nourishment as much as our outer (physical, intellectual and emotional) parts need nourishment. When this inner part is nourished well it leads to a more meaningful and more productive outer life. Belief in the spiritual (the transcendental) holds that development of the spirit (the soul) is as important as, if not more important than, development of the mind and the physical body. Spiritual managers realize that work can either damage or nurture one’s inner self. For spiritual employees, meaningful work means work that gives meaning to their work-lives, work that doesn’t conflict with their inner beings, work that gives opportunities to contribute to the general well being of the immediate community and humanity in general. In other words, meaningful work allows one to accomplish the purpose of one’s existence through one’s work (Novak, 1996; Chappell, 1994). Mitroff and Denton (1999) report that one of the factors that impart meaning and purpose to work is being associated with an ethical organization whose actions and decisions are guided by spiritually imbued values – actions and decisions that are deemed to be ethical and caring. Spirituality also comprises an awareness of the interconnectedness of everything in life and connectedness to other human beings. MBV managers create a work environment that is conducive to spiritual growth, which then fosters their connectedness to each other. Spiritual managers recognize this part of human nature and nurture it through meaningful work, through strong sense of community, and through interconnectedness. There is a strong belief among spiritual managers that such a work environment has powerful positive implications for organizational performance. It is important to note, though, that spiritual managers do not create such an environment as a means to increasing organizational performance. They believe that human beings are ends in themselves; performance and profit would naturally follow suit if MBV is practiced as an end in itself. In such an environment employees feel respected as human beings and they grow to their potential while accomplishing meaningful work that fulfills their need for human connectedness and community. Proposed Model It is clear from the above review of the literature on the concept this paper calls MBV that there are certain beliefs and virtues that are unique to those managers who actively practice this style of management. The main concepts associated with MBV are belief in a deity, belief in the meaningfulness and purposefulness of life, a feeling of community and connectedness, and an I-Thou attitude. The following section will Proceedings of 3rd Global Business and Finance Research Conference 9 - 10 October 2014, Howard Civil Service International House, Taipei, Taiwan ISBN: 978-1-922069-61-0 describe the proposed model, which will attempt to explain the motivational processes and dynamics involved in the practice of MBV. The MBV manager is driven or motivated by a religious ideology. Based on this religious ideology, the leader articulates a vision that is transcendental in nature. The vision agrees with the moral values derived from the manager’s spirituality. Spirituality addresses three fundamental aspects of life: belief in the transcendental deity, purpose of life, and assumptions about human nature. Human beings are not viewed as selfish utility maximizers but are driven by moral values, which are derived from religious principles. These moral values emanate from deeply held beliefs of self-perception and self-esteem. Their practice of spirituality motivates them to maintain their self-esteem. According to House and Shamir (1993), self-esteem has two components: self-worth and self-efficacy. “Feelings of self-worth are derived from a sense of virtue and morality and are grounded in social norms and cultural values concerning conduct” (p. 89). Self-efficacy has to do with a person’s belief in his/her ability to accomplish tasks. Moral values also motivate people to ensure that their behaviors are congruent with their beliefs. Finally, beside self-identity, human beings also have a strong collective identity, which sometimes can override selfish motivations. The concept of faith in a better future, that efforts bring about results, and that the importance of keeping hope are also integral to the assumptions that motivate people to be persistent. MBV allows leaders to increase followers’ level of self-worth, self-efficacy, faith in a better future, and commitment to the values espoused in the leader’s religiously inspired vision. The leader taps into the motivational powers of the self-esteem, selfworth, and community identification of the followers. Thus the followers’ values and self-concepts are engaged in such a way that their behaviors are aligned with their moral values. This makes them less concerned with selfish gains and more with community welfare. The above behaviors are expected to have intensive motivational effects on the followers. They raise their self-consistency, self-esteem, self-worth and heighten faith in what the future holds. These effects will in turn produce organizational outcomes that are conducive to increased commitment, loyalty and organizational citizenship behaviors (performance beyond the call of duty that is required for the survival of the firm). Treating employees as ends in themselves ensures sincerity in the decisionmaking. Decisions about work design and work environment are made based on purity of intention and motive and not for public relations purposes only. One indication of sincerity on the part of management is leading by example. Virtues attributed to the IThou attitude (Chappell, 1994; Marcic, 1997) include trustworthiness, which entails accountability, honesty, integrity, and ethical behavior; sense of community, which ensures commitment to employees, reciprocity, coaching rather than controlling, and consensus building; treating others with respect and according them dignity; justice Proceedings of 3rd Global Business and Finance Research Conference 9 - 10 October 2014, Howard Civil Service International House, Taipei, Taiwan ISBN: 978-1-922069-61-0 which entails empathy and equitable compensation; and service (stewardship), which entails humility and selflessness. All of the above behaviors on the part of management lead to an organizational climate that encourages employees to be engaged not only intellectually, but also emotionally and spiritually. In such an environment, employees develop to their full potential. Managers and their subordinates raise one another to higher levels of morality and motivation. According to Chappell (1994), this in turn will lead to high morale, loyalty, and commitment on the part of workers and managers. Workers will also be more willing to go beyond the call of duty in carrying out their daily tasks. Organ coined the term Organizational Citizenship Behavior (OCB) to denote “individual contributions in the workplace that go beyond role requirements and contractually rewarded job achievements” (Organ & Ryan, 1995, p. 775). OCB goes beyond role requirements, being characterized by spontaneity and innovativeness. Organ agrees with Chester Bernard (1938) that such spontaneous behaviors are important for the effectiveness of any organization. Throughout any organization, there are countless acts of OCB, which members of the organization perform on a daily basis. Although these acts, taken for granted most of the time, may not individually amount to much of significance, they are indispensable for the smooth running of the operations of any organization. Organ (1988) argues that high occurrences of OCB “in the aggregate” should lead to more organizational effectiveness (p. 6). Regardless of how organizational effectiveness is conceptualized, ultimately it has to do with how efficiently the organization utilizes its productive resources and/or its success in procuring and retaining them. Organizations spend a substantial amount of resources on maintaining their internal social systems. The more resources the organization spends on internal maintenance, the less efficient it will be since those same resources could have been used for production of goods and services. Inasmuch as OCB contributes to lowering the cost of system maintenance and/or procurement and retention of tangible and intangible resources, it would render the system more effective. There are at least three empirical studies (Karambayya, 1989; Podsokoff & MacKenzie, 1994; and, Podsokoff et al., 1997) that have confirmed the positive effects OCB could have on organizational effectiveness as gauged by different measures of productivity. In today’s organizations, contextual performances like the ones encompassed in OCB, assume more weight and importance since it is becoming harder and harder to incorporate everything that needs to be done in in-role job descriptions. A research stream spawned by Bateman & Organ (1983) (Organ, 1988; Konovsky & Organ, 1996; Organ & Ryan, 1995; Podsakoff et al., 1997) delineated and refined OCB. OCB is defined to consist of such factors as Altruism (providing aid to a specific person, such as a coworker); General Compliance (conscientiousness in attendance, use of work time, respect for company property, and faithful adherence to rules about work procedures and conduct); Sportsmanship (demonstration of willingness to forbear minor and temporary nuisances without fuss, appeal, or protest); Civic Virtue (responsible and constructive involvement in the issues and governance of Proceedings of 3rd Global Business and Finance Research Conference 9 - 10 October 2014, Howard Civil Service International House, Taipei, Taiwan ISBN: 978-1-922069-61-0 the organization); and Courtesy (gestures taken to help prevent problems of work associates) (Organ & Ryan, 1995). Organ (1990) traces employee satisfaction, particularly that aspect of satisfaction that has to do with the cognitive appraisal of job conditions, as opposed to its dispositional aspects, as one of the major antecedents of OCB. As such, “OCB is deliberate and controlled, not impulsive or merely expressive of mood.” (p. 58). It is theoretically sound to expect higher OCB in MBV organizations, not only because these organizations claim a highly satisfied workforce, but also because of the perceived inherent fairness associated with them. Organ (1990) reports that a sizable part of job satisfaction measures and responses is attributed to the cognitive and fairness component of job satisfaction. Organ hypothesizes that “job satisfaction cognitions relate to OCB to the extent that they reflect fairness judgments,” which in themselves are cognitive judgments. Empirically Organ & Konovsky (1989) attempted to pin down which job satisfaction component, affective or cognitive, drives OCB. Their findings supported the hypothesis that cognitive job appraisals predict occurrences of OCB better than affective or mood states of employees can. Since MBV organizations are reputed to be extremely fair, it is reasonable to expect that they would score high on measures of OCB. Furthermore, Organ (1990) reports that Farh, Podsakoff, and Organ (1988) found that stimulating job characteristics (as per Hackman and Oldham, 1975) to be one of the predictors of OCB. As mentioned earlier in this study, MBV’s work meaningfulness is putatively more intense than Hackman and Oldham’s (1975) job meaningfulness. The findings of Farh and colleagues (1988) support that job meaningfulness has a direct effect on OCB independent of satisfaction or fairness. Organ (1990) offers a social exchange explanation of OCB. Social exchange organizations create cultures, which predispose them to emphasize the wholistic nature of a specific member’s contribution. In contrast, organizations based on economic exchange have a market culture, which predisposes them toward quid pro quo relationships with their members. MBV organizations are inherently predicated on social exchange not only in terms of their reliance on intensive socialization, but also the self-selected nature of their employees who seem to be a priori committed to the stated goals of the organization. Organ (1990) theorizes that the type of organizational exchange – economic or social – can either encourage or stifle the dispositional antecedents of OCB. MBV organizations seem to create an environment of socialization, which motivates its members to establish social exchange relationships, which in turn encourages a high incidence of OCB. In many respects, MBV organizations are similar to covenantal organizations, as described by Graham & Organ (1993). Graham & Organ (1993) classify organizations into transactional, social exchange and covenantal, depending on the type of contract underlying relationships among organizational participants. Both transactional and social exchange organizations are characterized by quid pro quo arrangements, predicated on a mix of self-interest, commitment as well as the value of fairness. In contrast, contractual relationships in covenantal organizations are not limited to dictates Proceedings of 3rd Global Business and Finance Research Conference 9 - 10 October 2014, Howard Civil Service International House, Taipei, Taiwan ISBN: 978-1-922069-61-0 of self-interest, although self-interest is not abrogated altogether. Covenantal organizations commit participants to “a transcendental set of values,” vision of a future state, and a mission of how to get there, all espoused by the leader (p. 490). Participants are motivated by a desire to realize these sets of transcendental values. Covenantal organizations bind participants into long-term and intensive relationships, which demand committed and active involvement of the whole person. Such organizations create a work environment that does not draw distinctions between in-role and extra-role behaviors. Similar to covenantal organizations, MBV organizations are characterized by strong organizational commitment (OC) and higher levels of OCB. Organ (1990) makes a clear distinction between OC and OCB. According to Organ, OC, or at least its affective dimension, precedes OCB. In their meta-analytic review of 55 empirical studies on OCB Organ and Ryan (1995) conclude that affective commitment correlates positively with OCB. O’Reilly and Chatman’s (1986) work assessed OC as a concept that denotes the strength of attachment to an organization. Mowday, Steers and Porter (1979) conceptualized organizational commitment as a form of identification with, and dedication of, one’s energies to the organization’s goals and values. As such, commitment consists of such factors as (1) belief in and acceptance of organizational goals and values, (2) willingness to exert effort towards organizational goal attainment, and (3) strong desire to maintain organizational membership. Allen and Meyer (1990) name these three components of commitment affective, normative and continuance, respectively. Other researchers lump together the affective and normative components. In this case, affective commitment refers to “the strength of an individual’s identification with and involvement in a particular organization” (Mowday et al., 1974, p. 604), whereas continuance commitment is the tendency to engage in “consistent lines of activity,” not because the individual necessarily has strong identification with the organization, but because of the perceived costs doing otherwise (Becker, 1960, p. 33.) Thus, affective and continuance commitments are driven by different motivations. According to Mowday and colleagues (1982) those who value and want to maintain membership in the organization should be willing to exert considerable effort on behalf of the organization. On the other hand, those who feel compelled to maintain membership to avoid financial or other costs may do little more than the minimum required to retain employment. Proceedings of 3rd Global Business and Finance Research Conference 9 - 10 October 2014, Howard Civil Service International House, Taipei, Taiwan ISBN: 978-1-922069-61-0 References Allen, N. & Meyer, J. (1990). The measurement and antecedents of affective, continuance and normative commitment to the organization. Journal of Occupational Psychology, 63: 1-18. Ashmos, D. & Duchon, D. (2000). Spirituality at work: A conceptualization and measure. Journal of Management Inquiry, 9(2), 134-144. Barnard, C. I. (1938). The functions of the executive. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press. Benefiel, M. (2003). Mapping the terrain of spirituality in organizations research. Journal of Organizational Change Management, 16(4), 367-377. Bierly, P., Kessler, E., and Christensen, E. (2000). Organizational learning, knowledge and wisdom. Journal of Organizational Change Management, 13(6), 595-618. Block, P. (1993). Stewardship: Choosing service over self-interest. San Francisco: Berret-Koehler. Bolman, L. and Deal, T. (1995). Leading with Soul. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass. Bryman, A. (1989). Research Methods and Organizational Studies. London: Unwin Hyman. Bryman, A. (1984). Organizational studies and concept of rationality, Journal of Management Studies, 21:391-408. Business Week (1995). Companies Hit the Road Less Traveled, June 5. Chappell, T. (1991). The Soul of the Business: Managing for Profit and the Common Good. Conger, J. & Associates (1994). Spirit at Work, San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass. Covey, S. (1990). Principle-Centered Leadership, New York: Summit. Cox, M. (1993). Business Books Emphasize the Spiritual, Wall Street Journal, December 14. Daaleman, T., Frey, B., Wallace, D. & Studenski, S. (2002). The spirituality index of well-being: Development and testing of a new measure. The Journal of Family Practice, 51(11), 1-9. Davis, J. H., Schoorman, F. & Donaldson, L. (1997). Toward a stewardship theory of management. Academy of Management Review, 22(1). 20-47. Dean, K. (2004). Systems thinking’s challenge to research in spirituality and religion at work: An interview with Ian Mitroff. Journal of Organizational Change Management, 17(1), 11-25. Dean, K., Fornaciari, C., & McGee, J. (2003). Research in spirituality, religion, and work: Walking the line between relevance and legitimacy. Journal of Organizational Change Management, 16(4), 378-395. DePree, M. (1989). Leadership is an art. New York: Doubleday. Doucouliagos, C. (1994). A note on the volution of homo economicus. Journal of Economics Issues, 3:877-883. Drexler, J. A. (1977). Organizational climate: Its homogeneity within organizations. Journal of Applied Psychology, Vol. 62, No. 1, 38-42. Economist (1997). Management theory’s true believers, July 19th, p. 59. Eisenhardt, K. M. (1989). Agency Theory: An assessment and review, Academy of Management Review, 14:57-74. Proceedings of 3rd Global Business and Finance Research Conference 9 - 10 October 2014, Howard Civil Service International House, Taipei, Taiwan ISBN: 978-1-922069-61-0 Etzioni, A. (1988). The moral dimension. New York: Crown Publishers. Etzioni, A. (1993). The Spirit of Community. New York: Touchstone. Findelstein, S. & Hambrick, D. (1996). Strategic Leadership: Top executives and their effects on organizations. St. Paul, MN: West Publishing Co. Gardner, H. (1995). Leading Minds, New York: HarperCollins. Graham, J. W. & Organ, D. (1993). Commitment and the covenantal rganization. Journal of Management Issues. Vol. V, Number 4, 483-502. Greenleaf, R. K. (1977). Servant Leadership: A journey into the nature of legitimate power and greatness. New York: Paulist Press. Hair, J. F., Anderson, R., Tatham, R. & Black, W. (1995). Multivariate Data Analysis with readings (4th Edition). Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall. Hair, J., Anderson, R., Tatham, R. & Black, W. (1995). Multivariate data analysis with readings. Fourth Edition. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall. Harman, W. (1988). Global Mind Change. New York: Warner. Harman, W. & Hormann, J. (1990). Creative Work. Indianapolis, IN: Knowledge Systems, Inc. Hawley, J. (1993). Reawakening the Spirit in Work: The Power of Dharmic Management. San Francisco, CA: Berrett-Koehler. Heaton, D., Schmidt-Wilk, J., & Travis, F. (2004). Constructs, methods, and measures for researching spirituality in organizations. Journal of Organizational Change Management, 17(1), 62-82. Heuberger, F. and L. Nash (Eds.). (1994). The Fatal Embrace? Assessing Holistic Trends in Human Resources Programs. New Brunswick, NJ: Transaction. Hickman, C. R. (1990). Mind of a manager, soul of a leader. New York: Wiley. Iannaccone, L. R. (1995). Risk, Rationality, and Religions Portfolios. Economic Inquiry, 33, 2, 285(11). Jensen, M. C. & Meckling, W. (1994). The nature of man. Journal of Applied Corporate Finance, 7(2), 4-19. Jones, T. M. (1991). Ethical decision making by individuals in organizations. Academy of Management Review, 16, 336-395. Kahn, W. A. (1992). To Be Fully There: Psychological Presence at Work. Human Relations, 45, 4, 321-349. Kahn, W. A. (1993). Caring for the Caregiver: Patterns of Organizational Caregiving. Administrative Science Quarterly, 38, 4, 539-563. King, J. & Crowther, M. (2004). The measurement of religiosity and spirituality: Examples and issues from psychology. Journal of Organizational Change Management, 17(1), 83-101. Kofman, F. & Senge, P. (1993). Communities of Commitment: The Heart of the Learning Organization. Organizational Dynamics, Fall. Kohn, J. S. (1990). The ethical side of human nature. New York: Basic Books. Konovsky, M. A & Organ, D. W. (1996). Dispositional and contextual determinants of organizational citizenship behavior. Journal of Organizational Behavior, Vol. 17, 253-266. Kouzes, J. M. & Posner, B. (1987). The leadership challenge. San Francisco: JosseyBass. Proceedings of 3rd Global Business and Finance Research Conference 9 - 10 October 2014, Howard Civil Service International House, Taipei, Taiwan ISBN: 978-1-922069-61-0 Krahnke, K., Giacalone, R. & Jurkiewicz, C. (2003). Point-counterpoint: Measuring workplace spirituality. Journal of Organizational Change Management, 16(4), 396-405. Laabs, Jennifer J. (1995). Balancing Spirituality and Work. Personnel Journal, 74, 9, 60(9). Learner, M. (1996). The Politics of Meaning. Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley. Lips-Wiersma, M. (2002). Analysing the career concerns of spirituality oriented people: Lessons for contemporary organizations. Career Development International, 7(7), 385-397. Lips-Wiersma, M. (2003). Making conscious choices in doing research on workplace spirituality utilizing the “holistic development model” to articulate values, assumptions and dogmas of the knower. Journal of Organizational Change Management, 16(4), 406-425. Mansbridge, J. J. (Ed.). (1990). Beyond self-interest. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. Marcic, D. (1997). Managing with Wisdom of Love: Uncovering Virtue in People and Organizations. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass Inc. Maslow, A. H. (1954). Motivation and Personality. New York: Harper. Maslow, A. H. (1968). Toward a Psychology of Being. New York: Van Nostrand. Mathews, M. C. (1987). Code of ethics: Organizational behavior and misbehavior. In W. C. Frederick and L. E. Preson (Eds.). Research in corporate social performance and policy: Empirical studies of business ethics and values (Vol. 9, pp. 107-130). Greenwich, CT: JAI Press. McCloskey, D. (1985). The loss function has been mislaid: The rhetoric of significance tests. The American Economic Review, 75(2), 201-205. McGregor, D. (1960). The Human Side of Enterprise. Englewood-Cliffs, NJ: PreticeHall. McIntyre, A. (1981). After virtue. North Bend, IN: University of Notre Dame Press. Meyer, J., Paunonen, S., Gellatly, I., Goffin, R., & Jackson, D. (1989). Organizational commitment and job performance: Its the nature of the commitment that counts. Journal of Applied Psychology, Vol. 74, No. 1, 152-156. Milliman, J., Czapleski, A., & Ferguson, J. (2003). Workplace spirituality and employee work attitudes: An exploratory empirical assessment. Journal of Organizational Change Management, 16(4), 426-447. Milliman, J., Ferguson, J., Trickett, D., & Condemi, B. (1999). Spirit and community at Southwest Airlines: An investigation of a spiritual values-based model. Journal of Organizational Change Management, 12(3), 221-233. Mirvis, P. H. (1997). Soul Work in Organizations. Organization Science, 8(2) 192-206. Mirvis, P. H. (1980). The Art of Assessing the Quality of Work Life, in E. Lawker, D. Nadler, and C. Camman (Eds.). Organizational Assessment. New York: Wiley Interscience. Mitchell, T. R. & Scott, W. G. (1987). Leadership failures, the distrusting public, and prospects of the administrative state. Public Administation Review, (Nov./Dec.), 445-452. Proceedings of 3rd Global Business and Finance Research Conference 9 - 10 October 2014, Howard Civil Service International House, Taipei, Taiwan ISBN: 978-1-922069-61-0 Mitchell, T. R. & Scott, W. G. (1990). Americas problems and needed reforms: Confronting the ethic of personal advantage. Academy of Management Executive, 4, 23-35. Mitchell, T. R. (1993). Leadership, values, and accountability, in Chemers, M. M. & Roya Ayman, eds. Leadership theory and research: Perspectives and directions. San Diego, CA: Academy Press, Inc., pp. 109-136. Mogelonsky, M. (1992). Cafeteria-Style Churches. American Demographics, 14, 12, 57(1). Mohoney, M., & Graci, G. (1999). The meanings and correlates of spirituality: Suggestions from an exploratory survey of experts. Death Studies, 23, 521-528. Moore, T. (1991). Care of the Soul: A Guide of Cultivating Depth and Sacredness in Everyday Life. New York: Harper-Collins. Moorman, R. H. (1993). The influence of Cognitive and Affective based Job Satisfaction Measures on the Relationship between Satisfaction and Organizational Citizenship Behavior. Human Relations, vol. 46, No. 6, pp. 759-776. Mowday, R. T., Steers, R., & Porter, L.. (1979). The measurement of organizational commitment. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 14: 224-247 Mowday, R. T., Steers, R., and Porter, L. (1982). Employee organization linkage: the psychology of commitment, absenteeism, and turnover. New York: Academic Press. Mowday, R., Steers, R. & Porter, L. (1979). The measurement of organizational commitment. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 14, 224-247. Nadler, D. A. & Tashman, M. (1989). What makes for magic leadership, in W. E. Rosenbach & R. L. Taylor (eds). Contemporary Issues in Leadership. Boulder: Westview. Nadler, D. A. & Tashman, M. (1990). Beyond the charismatic leader: leadership and organizational change. California Management Review, 32: 77-97. Niebuhr, H. R. (1963). The Responsible Self. New York: Harper and Row. Noreen, E. (1988). The economics of ethics: A new perspective on agency theory. Accounting, Organizations and Society, 13, 359-369. Nur, Y. (1998). Charisma and managerial leadership: the gift that never was. Business Horizons. July/August. Organ, D. W (1990). The motivational basis of organizational citizenship behavior. In Barry Staw & Cummings L. L. (Eds.). Research In Organizational Behavior, Vol. 12 (pp. 43-72). Greenwich, CT: JAI Press, Inc. Organ, D. W. & Ryan, K. (1995). A meta-analytic review of attitudinal and dispositional predictors of organizational citizenship behavior. Personnel Psychology, 48: 775-802. Organ, D. W. (1988). Organizational citizenship behavior: The good soldier syndrome. Lexington, MA: Lexington Books. Palmer, P. J. (1990). The active life: A spirituality of work, creativity, and caring. San Francisco: Harper and Row. Perrow, C. (1986). Complex organizations: A critical essay. (3rd ed.) New York: Random House. Proceedings of 3rd Global Business and Finance Research Conference 9 - 10 October 2014, Howard Civil Service International House, Taipei, Taiwan ISBN: 978-1-922069-61-0 Podsakoff, P. M., MacKenzie, S., Moorman, R. & Fetter, R. (1990). Transformational leader behaviors and their effects on followers trust in leader, satisfaction, and organizational citizenship behaviors. Leadership Quarterly, 1:107-42. Pollard, C. W. (1996). The Soul of the Firm. New York: HarperBusiness. Ray, M. & Rinzler, A. (1993). The New Paradigm in Business. New York: Tarcher/Perigee. Ritscher, J. E. (1986). Spiritual leadership. In J. Adams (ed.). Transforming leadership: From vision to results, (pp. 61-80). Alexandria, VA: Miles River Press. Rothschild-Whitt, J. (1979). The Collectivist Organization: An Alternative to RationalBureacratic Models. American Sociological Review, 44, 509-527. Sashkin, M. & Burke, W. (1990). Understanding and assessing organizational leadership, in K. E. Clark and M. B. Clark (eds). Measures of leadership. West Orange, NJ: Leadership Library of America. Sashkin, M. (1986). True vision in leadership. Training and Development Journal, 40, 58-61. Sashkin, M. (1988). The visionary leader, in J. A. Conger and R. N. Kanungo (eds). Charismatic leadership: the elusive factor in organizational effectiveness. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass. Schein, E. H. (1985). Organizational culture and leadership. San Francisco: JosseyBass. Schneider, B. (1987). The people make the place. Personnel Psychology, 40:437-453. Schmidt-Wilk, J. (2003). TQM in Europe: A case study ‘TQM and the Transcendental Meditation Program in a Swedish top management team’, The TQM Magazine, 15(4), 219-229. Scott, M. & Rothman, H. (1992). Companies with a Conscience. New York: Birch Lane Press. Scott, W. R. (3rd Ed.). (1992). Organizations: Rational, natural, and open systems. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall. Shamir, B, House, R. & Arthur, M. (1993). The motivatinal effects of charismatic leadership: a self-concept based theory. Organization Science, Shamir, B. (1991). Meaning, self and motivation in organizations. Organization Studies, 12:405-424. Shepard, J. M., Shepard, J., Wimbush, J., & Stephens, C. (1996). The place of ethics in business: shifting paradigms? Business Ethics Quarterly, pp. 577-601. Singleton, R., Straits, B. & Straits, M. (1993). Approaches to social research. New York: Orford University Press. Thurow, L. C. (1984). Dangerous currents. New York: Vintage Books. Tversky, A. & Kahneman, D. (1971). Belief in the law of small numbers. Psychological Bulletin, Vol. 76, No. 2, 105-110. Vail, P. (1990). Managing as a performing art. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass. Whetten, D. A. & Cameron, K. S. (1996). Organizational effectivness: Old models and new constructs, In Jerald Greenberg (Ed.). Organizational behavior: State of the science. Williamson, Oliver E., ed. (1990). Organization Theory: From Chester Barnard to the present and beyond. New York: Oxford University Press.