REAL ESTATE TRANSACTIONS & FINANCE Fall 2015 Tender/Time of Performance

advertisement

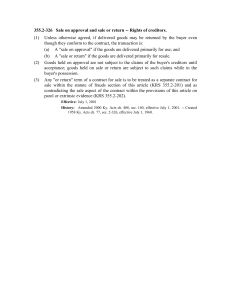

REAL ESTATE TRANSACTIONS & FINANCE Fall 2015 Tender/Time of Performance Equitable Conversion and Risk of Loss Reading Assignment: NWBF pages 73-83 and 96-113 1. Miller v. Almquist (page 73) deals with a contract to purchase a cooperative unit. If you aren’t familiar with the structure of a housing cooperative, there’s a brief introduction and background beginning on page 1205 of the Casebook. Unlike in a condominium, where the buyer gets fee simple title in the interior of his/her unit, the cooperative member buys a share of stock in the housing cooperative (which owns the entire building), and then signs a “proprietary lease” with the housing cooperative that entitles the buyer to occupy their apartment within the building. What would be the relative advantages or disadvantages of buying a unit in a cooperative rather than buying a condominium unit? 2. Note 1 (page 78) after Miller states that the buyers in Miller “could have obtained specific performance if they had wanted it.” How can this be correct, given that the sellers “subsequently sold the premises to a third party at a higher sale price” (page 77)? If the third party did not know about the dispute between the Millers and the Almquists, why wouldn’t the sale to a third party defeat the buyers’ ability to obtain specific performance of the contract? 3. Note 4 (page 81) suggests that Miller demonstrates the ability of a party to the contract to make time of the essence of the contract — even if it was not originally “of the essence” — by giving a unilateral notice to the other party. Such a notice will be binding on the other party, as long as the new “essential” date is not unreasonable. Is this giving one party the unilateral ability to modify the contract? 4. Does the court in Grant v. Kahn (page 97) reach the normatively correct result? Does it make sense for the court to apply equitable conversion and thus conclude that the Kahn’s judgment did not constitute a lien on Grant’s equitable interest in the land as Buyer? Is a buyer in Grant’s position powerless to protect himself or herself other than by application of equitable conversion? How else could Grant protect against this risk? 5. Compare the situation in Grant with the situation of a buyer under an installment land contract. Suppose Crouch was purchasing land from Litton on an installment contract, under which he had been making monthly payments for 5 years (and had only 25 years to go!) at the time Mitchell obtained a judgment against Litton. Is the application of equitable conversion in that context more compelling than in Grant v. Kahn, or less compelling? 6. Look back at the “Risk of Loss” clause in the example form contract that appears in the casebook on page 29. What changes (if any) might you suggest if you were representing the Buyer in negotiating a contract using this form? If you were representing the Seller in negotiating the contract?