Proceedings of World Business, Finance and Management Conference

advertisement

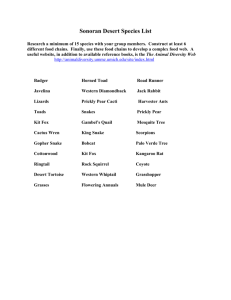

Proceedings of World Business, Finance and Management Conference 14 - 15 December 2015, Rendezvous Grand Hotel, Auckland, New Zealand ISBN: 978-1-922069-91-7 Determinants of Pear Farmers’ Profits in China* Shamim Shakur1 and Yan Wang2 Pear output and acreage in China has been increasing steadily since market deregulations were introduced in 1980s. However, like other horticulture producers, typical pear farmer in China remain small-scale operators and price-takers in both input and output markets. Moreover, farmers can be efficient in production but not in profit as the latter depends on organizational and marketing skills. We investigate profitability of China’s pear farmers in this study. We conducted annual survey on 184 Chinese pear farmers from eight leading pear-producing provinces. Our primary data contains details on pear price, production cost, pear variety and socio-economic variables. We summarize useful observations on these variables in statistical tables. Our regression results capture the relative importance of these variables in terms of their contribution to profits. Specifically, we find that choosing the “correct” pear variety and selling channel is more important than many other perceived determinants of profit. JEL Codes: Q12, Q13, P22 Keywords: China, Pear, Profit function Name of the Track: Economics 1.0 Introduction Until the early 1980s, China‟s agricultural sector was organized almost entirely according to the commune system. By mid-1980s, the commune system was all but dissolved in favour of a contract responsibility system. Under such responsibility system, farmers were obligated to sell a certain amount of their harvest at a predetermined price to their village unit; the remainder could be sold in the open market. Subsequent market reforms and deregulations meant majority of Chinese farmers currently are left to face the challenges and opportunities of the market. Reforms also encouraged farmers to plant orchards, and the output of apples and pears, in particular witnessed extraordinary growth. China is ______________________________________________ 1 Corresponding Author, Senior Lecturer in Economics, School of Economics and Finance Massey University, New Zealand, Tel: +64 6 356 9099 ext. 84069, Email: S.Shakur@massey.ac.nz 2 Associate Professor, College of Economics and Management, Nanjing Agriculture University, P.R. China and Visiting Scholar at School of Economics and Finance, Massey University, New Zealand, Email: wyan@njau.edu.cn * The authors acknowledge the sponsorship of “the earmarked fund for China Agriculture Research System” (No:CARS-29), National Natural Science Foundation of China (No.71103087) and “A Project Funded by the Priority Academic Program Development of Jiangsu Higher Educational institutions (PAPD)”. Proceedings of World Business, Finance and Management Conference 14 - 15 December 2015, Rendezvous Grand Hotel, Auckland, New Zealand ISBN: 978-1-922069-91-7 currently the world‟s largest horticultural producer and consumer. Despite this unprecedented growth in production, a typical horticultural farmer in China can best be described as a small scale operator characterized by a price-taking behavior in both input and output markets. They have no capacity to bargain a better price with either processors or wholesalers of their produce. Unless they subscribe to a farmer‟s organization, isolated farmers, trapped at the lowest end from a supply chain perspective, are left vulnerable to price and revenue volatility. A very specific question we address is how to improve farmers‟ profit. To answer this question, one has to take a closer look at the determinants of profit. Since profit is calculated by revenue net of cost, there are two ways to improve profit; increase revenue or reduce cost. Revenue can be increased by producing more output or by obtaining a higher price. Output can be increased by adopting to better farming methods that includes switching to high yielding varieties of produce or large scale farming. Price obtained is determined by the market environment and producer participation in alternative marketing channels. Cost can be reduced by increasing productivity or using less input. By examining the determinants of a standard profit function, this paper is able to make specific recommendations to raise profitability of Chinese pear farmers. 1.1 Pear Variety in China Currently China leads the world in terms of cultivation area and output with an overwhelming dominance in Asian pear variety. There are 96 Chinese local pear cultivars in addition to 52 varieties bred and released by horticulture scientist (Cao, 2014). Some varieties have been introduced from Japan, Korea or the West such as Housi, Kosui, whangkeumbae, Wonhwang and Bartlett. Through long-term natural selection and production development, four regions of China emerged as main pear growing area. These are (1) Bohai region (Liaoning, Hebei, Beijing, Tianjin, Shandong) for surian and White Pear; (2) Western China (Xinjiang, Gansu, Shaanxi, Yunnan) for White Pear, (3) old basin of Yellow River (Henan, Anhui, Jiangsu) for White and Sand Pear, and the (4) Yangtze River Valley (Sichuan, Chongqing, Hubei, Zhejiang) for Sand Pear. In 2014 the top five varieties of harvested area were Yali, Suli, Huangguan, Nanguoli and Korla Pear, accounting for 27.29%, 15.88%, 9.19%, 8.63% and 5.86% respectively, as per our survey in the main pear planting regions. In terms of the regional distribution, Yali grows mainly in Hebei province, Suli in Shanxi and Henan Province, Huangguanis in Hebei, Nanguoli in Liaoning and Korla in Xinjiang. For other varieties, production is more dispersed. Cuiguan grows in Chongqing, Jiangxi, Fujian and Zhejiang; Huanghua has been cultivated in Chongqing, Fujian, Jiangxi and Hubei; whangkeumbae is mainly located in Shandong, Beijing and Hebei; Housi in Shandong, Sichuan, and Jiangsu; Yuanhuang is produced in Henan, Jiangsu, Hubei and Chongqing. Among these varieties, Chinese local cultivars include Yali, Suli, Nanguoli, Korla Pear, Xuehuali, Pingguoli and CangxiXueli. Breeding varieties consist of Huangguan, Cuiguan, Huanghua, Zaosu, Yuluxiang, Qingxiang and LongyuanYangli. Whangkeumbae and Wonhwang come from Korea and Housi was introduced from Japan. Proceedings of World Business, Finance and Management Conference 14 - 15 December 2015, Rendezvous Grand Hotel, Auckland, New Zealand ISBN: 978-1-922069-91-7 1.2 Pear Market In 1985, the Chinese government relaxed the regulatory environment surrounding fruit production and marketing. Market-oriented production and transaction encouraged fruit producers including that of pear as terms of trade improved over rival grain production. Pear output and acreage grew steadily as a result. During 1990s, large-scale wholesale markets gradually became a key part of fruit transactions, functioning alongside farmers‟ market and small scale vegetable and fruit market, including that of pear. A flow chart of pear marketing channel is shown below. Figure 1: Pear Marketing and Sales Channel Exporter or processing firm Farmer orgnization Storage Pear farmer Field broker Market at producing area Wholesaler City wholesale market Retailer Supermarket or fruit store consumer Pick your own Brokers typically work as agents connecting pear farmers with wholesalers. Knowledgeable about major planters and the farming community, they purchase pear as representatives of wholesalers. Brokers gain brokerage without possessing pear, therefore do not bear the risk of market price fluctuations. To their advantage, wholesalers purchase pear from brokers instead of dealing directly with farmers due to lower transaction cost. Wholesalers in their part transport and distribute pear to wholesale markets in city centres. At the prospect of selling pear at a higher price, brokers also take the risk of price fluctuations and attrition during transportation. In some situations, wholesalers are observed to be experienced pear farmers with large scale production. On arrival at a wholesale city market, pear is purchased by retailers from supermarkets, fruit shops or street vendors. Retailers typically obtain a premium price but also bear the risk of market price fluctuations and potential losses from product spoilage and pilferage. Wholesalers also store a part of their acquired pear in cold warehouses in order to sell off-season when price is higher. However, the storage merchants still have to face the risk of fluctuations in market prices. New season pear typically enters the market in June. On their own, farmers find it difficult to sell their produce because of lack of access to prompt and accurate market information. Many frustrated farmers even quit planting because of this. Similarly many distributors or wholesalers also complaint of high transportation costs impacting on margins. A phenomenon that emerged in recent years is when farmers quit harvesting because of low price simultaneously when urban households Proceedings of World Business, Finance and Management Conference 14 - 15 December 2015, Rendezvous Grand Hotel, Auckland, New Zealand ISBN: 978-1-922069-91-7 complained of high price. The response from the Chinese government was to initiate a support program “connecting farmers with supermarket” which helps farmers sell their products to supermarket directly, guaranteeing a steady supply of fruits and vegetables to urban residents. The program encourages large supermarkets establish stable purchase and sale contracts directly with farmers. However, lack of familiarity with individual farmers and associated high transaction cost prompts supermarkets to sign contracts with farmer cooperatives or agricultural associations instead of individual farmers. With the development of electronic commerce extending to agricultural products, pear is also currently being sold via network platform in addition to other traditional channels stated above. At this stage, online selling is dominated by branded pears of premium quality. 1.3 Pear Farmers’ Cooperative Organization Following China's reform and “open door” policy, various farmers' cooperatives emerged as an important form of production and management organization. The process got a boost from implementation of "Farmer Cooperatives Law" in 2007. Statistics published by the Chinese Ministry of Agriculture indicate a total of 689,000legally registered farmer cooperative organizations in operation in 2012. The number of farmers who join such a farmer cooperative organization stand at more than 4,600 million, accounting for 18.6% of the total rural households. An increasing volume of land is being converted from small farming to large scale farms, cooperative organizations and agribusiness firms, accounting for 61.8%, 18.9% and 9.7% respectively among all the land conversions. Our survey returns show that Shanxi, Hebei and Shaanxi have the largest concentration of pear farmers‟ cooperative organizations. Core farmers are those that have shares in Farmers‟ cooperative organization. These farmers have certain advantages over those that do not subscribe to similar organization. For example, core farmers obtain training in new techniques or technology adoption and have more opportunity to secure a higher price. In addition, members may get certain dividend income each year. Some cooperative organizations, however, are seen as more keen to secure subsidy from government than aiming to help farmers producing or selling their produce. 2.0 Literature Review Generally speaking, existing literature addresses the question of farm‟s production and profit efficiency in terms of marketing activities, financial constraints, farm-specific factors and farmer-specific characteristics. In this research, we consider a series explanatory variable that includes farmers‟ characteristics (education, experience, non-farm income), product variety, farm size, marketing channel and collective action to explain profitability of Chinese pear farmers. Productivity and Profit Efficiency Productivity reflects the relationship between input and output where efficient use of resources can achieve high productivity. Farrell (1957) is frequently credited for his pioneering work on the measurement of production efficiency. In later analysis, production Proceedings of World Business, Finance and Management Conference 14 - 15 December 2015, Rendezvous Grand Hotel, Auckland, New Zealand ISBN: 978-1-922069-91-7 efficiency is divided into technical, allocative and scale efficiency. Popular estimation approaches to production efficiency include Cobb-Douglas and stochastic frontier production functions. Efficiency in production does not always translate into profit. Farmers can be efficient in productivity but inefficient in profit. Profit efficiency requires achieving maximum profit that depend on output price and input cost. So profit efficiency can capture the inefficiency associated with inappropriate allocation of factors resulting in losing out on potential profits. Such inefficiency is prevalent in farming. Ali and Flinn (1989) investigates the case of Basmati rice production in Pakistan‟s Punjab province where the mean level of profit inefficiency at farm resources and price levels was calculated at 28 percent, with a wide range of variations around this mean of 5%-87%.The profit inefficiency here was shown to be related to farm household's education, non-agricultural employment, credit constraint, water constraint and the late application of fertilizer. Doole (2015) conducted his study on pasture-based dairy farming in New Zealand‟s Waikato region. He found that maximizing milk volume reduces operating profit by 12%–23% due to higher production costs. In another study by Nwauwa et al. (2013), profit efficiency of small-scale dry season fluted pumpkin averaged 0.925. Farmers‟ experience and farm size contributed to the explanation of efficiency levels in their study. Product/Crop Diversity Product diversity can be useful in making full use of the labour force. Crop diversification was found to increase productivity and affect farm income positively in a study by Ansoms, Verdoodt, and Van Ranst (2008). In a later study, Qasim (2012) found such effects to be statistically insignificant. For smallholder farmers that lose scale economy due to land fragmentation, they may acquire scope of economy from product diversity. At the same time, diversification is a key to greater wealth and to reduced vulnerability on livelihood as Block and Webb (2001) found in case of rural Ethiopia. Education and Experiences Human capital is crucial in raising productivity and profit. Lockheed, Jamison, and Lau (1980) found that farm productivity increases, on the average, by 7.4% as a result of a farmer's completing four additional years of elementary education compared to none. In a similar finding Anríquez and Valdes (2006) calculates high returns from education in terms of elasticity measure. Specifically, if the education level of the household head were to rise by 10 percent, the net revenues would rise by about 8 percent. Besides education or schooling, farmer experiences in cropping or planting also enhances profit. Farm Size In terms of scale economy, an optimal production scale can conceivably be found, which is measured by farm size or operational land. In general, operational size has positive effects on farm revenue. Medium and large farm renters would be willing to pay more than observed rents, implying an incentive to increase farm size(Anríquez and Valdes, 2006). In some cases, though, farm size can have inverse relationship with land productivity due to Proceedings of World Business, Finance and Management Conference 14 - 15 December 2015, Rendezvous Grand Hotel, Auckland, New Zealand ISBN: 978-1-922069-91-7 failure of land market, credit market, insurance market and labour market (Qasim, 2012). Off-Farm or Non-Farm Income Off-farm and non-farm income sources are more important for small farmers, contributing to their economic viability (Anríquez and Valdes, 2006). However, the role of non-farm income on productivity and profitability of farming operations can be ambiguous. Off-farm income might result in neglect to the farm management but increase the use of fertilizer and pesticide (McNally, 2002). In contrast, Qasim (2012) argues that young family members engaged in off-farm employments would frequently take leave from their employers and help farm household during the harvesting time. So off-farm income has positive relationship with farm profit. Marketing Activities Sales price is a key determinant of farmers‟ profit and participation of farmers in innovative marketing channels can acquire higher margins. Typically, marketing organisations would charge a membership fee for their services. One advantage is that cooperation decreases transaction costs(Verhaegen and Van Huylenbroeck, 2001). Presumably the savings on private transaction costs offset the higher costs for subscribing farmers. Most importantly, higher costs are compensated for by higher revenues due to higher prices and a higher turnover and by reduced uncertainty. Tegegne et al. (2012) noticed that Farmers working off farm tended to use middlemen due to time constraint. Farmers’ Organization and Collective Action Most small farmers find it difficult to market their products. The main value of farmers‟ organization and collective action is to provide more valuable and profitable sales channel. Farms participating in collective groups have opportunities to realize scale economies in production and input purchases that augment profit. Lower transaction costs associated with market access is the main beneficial feature of a farmer organization. Lead farmers provide local services at lower cost than donor subsidized models. So the economic viability of organization with donor subsidized or public support is questionable (Hellin, Lundy, and Meijer, 2009). The collective groups are generally inclusive of poor farmers, but ownership of agricultural assets and ability to access credit significantly increase the probability of joining a group. Fischer and Qaim (2012) argue that collective action can spur innovation. Group participation has higher adoption rates of technology and chemical inputs. In summary, existing literature on profit functions centres on single product analysis of rice (Ali and Flinn, 2006; Anríquez and Valdes, 2006), beef (McDonald and Schroeder, 2003), vegetable (Nwauwa et al., 2013). Very few (Evenson and Gollin, 2003) have considered the effect of product variety and none on pear farmers‟ profit that is the focus of this research. In this paper we identify the determinants of pear farmers‟ profit and focus on the effects of pear variety, marketing channels and participation in farmers‟ organization on profit. Proceedings of World Business, Finance and Management Conference 14 - 15 December 2015, Rendezvous Grand Hotel, Auckland, New Zealand ISBN: 978-1-922069-91-7 3. Data and Methodology 3.1 Pear Farmer Survey Primary data for the study was collected from a survey on pear farmers conducted annually from 2011 to 2014. Investigation sites were in the main pear producing provinces of Hebei Province (HB), Shanxi Province(SX), Shandong (SD), Shanxi (SXi), Jiangsu (JS), Jilin (JL), Xinjiang (XJ) and Fujian (FJ). A total of 597 observations were collected from these provinces over a period of 2011 to 2014 that are summarized in Table 1. On an average, 84% of the farmers responded each year that provided us with adequate information pear production and related socio-economic characteristics. Table 1: observations in the survey Provinces JS HB 18 21 farmers 15 13 2011 18 19 2012 15 19 2013 15 19 2014 Total 63 70 Observations Data source: from our survey repetition ratio XJ JL FJ SXi SX SD total 27 15 17 21 21 21 16 19 19 19 29 21 19 27 27 21 17 19 19 19 18 15 18 18 18 23 18 20 23 19 184 130 149 161 157 73.03% 83.71% 91.57% 88.20% 74 73 94 74 69 80 597 84.13% Farmers report their pear income each year but cost information in respect to all produced varieties is contentious. Many farmers produce a multitude of pear varieties but our questionnaire asked them to report cost on three of their top varieties. This was done as farmers do not always know full costing of the minor varieties and to increase response rate. We calculated farmers‟ profit of three largest varieties and then added them together to form total profit for each farmer. In regard to cost, we classified total cost into land, labour, material fee and capital cost. Our survey instrument was designed to extract information on various aspects of pear production and farmer characteristics as summarized in Table 2. Table 2: Content of the questionnaire Farmers’ characteristic Farmers’ Income Detailed information Name, county, province, year Gender, age, if be head of village, education, family population, if be communist party member, how long to plant pear, if be member of farmers‟ cooperative organization Total income of the whole family, share of agricultural income, Proceedings of World Business, Finance and Management Conference 14 - 15 December 2015, Rendezvous Grand Hotel, Auckland, New Zealand ISBN: 978-1-922069-91-7 Pear income, share of pear income Fruit area, pear area cultivated, pear area harvested, Pear production output, tree age respectively of three varieties; the distance between pear orchard and wholesale market, wages per capital per day Total production cost, land rent, fertilizer, manure, Production cost irrigation pesticide, herbicide, swelling agent, bag, box, pollen, bee, scaffolding, instrument to harvest; employee cost, self-employ cost, machine fee, of three major variety respectively Sales price and High price, low price, average price respectively of three varieties; different channel to sale such as self-sales, by channel wholesaler, by firm, by cooperative organization, be storage; the percentage of each channel Technique and If adopt new technique and the technique name, if take part in training and training times; time of update variety training and the reasons; if adopt standard technique; if know model of pear orchard; problems in planting 3.2 Methodology Our econometric estimation is based on a simple model that sets out the determinants of profit from pear farming as follows: Profit=α0 + α1j Variety + α2k Channel + α3 Organization + α4l Control + ε (1) Dependent Variable Profit per hector is calculated by revenue less cost for farmers respectively and winsorised by 0.01 and 0.99 to drop the outliers. Farmers do not always operate on their profit frontier as inputs are not chosen optimally or existence of asymmetric information on pear market. In addition, negative profit could exist in the short run. Many farmers reported negative profits during the survey period. (2) Explanatory Variables Our primarily interest lies in three kinds of variables that include pear variety, sales channel and participation in farmers‟ organization. Dummy variables are constructed to assess the effect of these variables. Variety is some dummy variables to reflect Yali, Suli, DangshanSuli, Korla, Huangguan and Huanghua. Channel is dummy variable representing selling to (i) wholesalers or to (ii) firms and farmers‟ organizations. Organization is also a dummy variable. It means farmer taking part in cooperative organizations if it takes on a value of 1. Proceedings of World Business, Finance and Management Conference 14 - 15 December 2015, Rendezvous Grand Hotel, Auckland, New Zealand ISBN: 978-1-922069-91-7 (3) Control Variables In addition to variables of our primary interest, a complete model should include other fundamental factors that affect profit. These are lumped together under control variables. Farm Specific Control Variables Area represents pear area that is harvested; not the area that is cultivated. This approach excludes the influence of natural disaster like extreme cold weather or drought. Price is the average price obtained and yield is calculated at the level of each farmer. In order to test for the effect of technology on profit, a new technique variable is included among control variables. Farmer specific control variables Farmer‟s age, education, experience and share of non-agricultural income also impacts on profit. We observed that among China‟s pear farmers, age is highly related to their experience. That means only one of the variables should be considered in the model. We chose farmers‟ age for our model estimation. 4.0 The Findings 4.1 Determinants of Pear Profit Profitability from horticultural production depends on acreage, yield, input price and output price. Returns from our survey of Chinese pear production indicate wide variations in reported profits including losses by many farmers. In terms of cost, farmers are price-takers in the input market paying essentially similar prices across the regions. But farmers can choose what pear variety to plant and how to sell pear from among alternative sales channels. As such, profit can vary across pear varieties and management capabilities. (1) Pear Variety In its long-history of production, over a hundred varieties of pear have been cultivated in China with various degrees of success. In our survey, a total of 24 pear varieties are reported as being planted by farmers that exhibit large variations in profit among these varieties. On the average, at over thirty thousand yuan per hectare, Huangguan and lvbaoshi show the highest profit. Xinshiji, Cuiguan, DangshanSuli, Korla, Hosu, Huanghua, Hongxiangsu and Xingaogain are the other highly profitable varieties with an average profit over twenty thousand yuan per ha. In regard to acreage, pear varieties with largest area harvested are Yali, Sulu, Huangguan and Korla with a combined acreage of 58% of the total pear planting area. Of these, Huangguan pear is bred by Chinese scientists while the remaining three are local, traditional varieties. In our regression estimates, we generate dummy variables to show the effects of pear variety on profit. Proceedings of World Business, Finance and Management Conference 14 - 15 December 2015, Rendezvous Grand Hotel, Auckland, New Zealand ISBN: 978-1-922069-91-7 (2) Sales Channel When it comes to selling the fruit, pear farmers in China can choose from three alternative sales channels: (1) selling by farmers themselves, (2) by wholesalers and (3) by firms and farmers‟ organizations. Only a few farmers (16%) chose to sell by themselves although selling this way can mean negotiating a higher price and profit than selling to the wholesalers. Some processing or trading firms purchase pear directly from farmers at a better price but also at a transaction cost and an opportunity cost that varies widely among farmers. Farmers that chose to sell via organizations also acquire higher profit. A summary of these prices obtained in our survey from alternative sales channels and associated harvested are reported below in Table 3. Table 3: Average price and profit by channel channel Average price (yuan/kg) Profit hectare (yuan/ha) 1.7024 5823 1 1.6026 2091 2 2.1078 20281 3 Source: Calculations based on our survey per (3) Participating Farmers’ Organization In our investigation of China‟s pear farming, we found that the farmers‟ cooperative organizations can play a useful role in planting and selling of the final product. As the table below would indicate, farmers that are members of a cooperative organization, on the average, obtain a higher price and profit compared those that do not belong to such organization. The significance of such differences still needs further investigation. From our survey, we also noted that 28.8% of pear farmers that participated in farmers‟ cooperative organizations did not sell pear via that channel. So participating in an organization does not necessarily mean selling through that organization and that there are other benefits of belonging to these organizations. Table 4 average price and profit by joining organization Member organization of Average price (yuan/kg) Profit hectare (yuan/ha) 1.6905 2294 0 1.7273 7163 1 Source: Calculations based on our survey per Proceedings of World Business, Finance and Management Conference 14 - 15 December 2015, Rendezvous Grand Hotel, Auckland, New Zealand ISBN: 978-1-922069-91-7 4.2 Variance Analysis We identify whether there are significant differences in profit in relation pear variety, sales channel or membership to farmers‟ cooperative organization. One-way analysis of variance is adopted to estimate the significance on group mean statistically. Yali, Suli, DangshanSuli and Korla pear are traditional varieties. Huangguan and Huanghua are bred by horticultural scientist. Yali, Suli and Huanghuahas negative mean profit, Dangshansuli and Huangguan has higher profit among al pear varieties. Analysis of variance illustrate there is significantly different profit between varieties. Sales channel 1 to 3 is selling by farmers, by wholesalers and by firms or organization respectively. Profits differ with respect to sales channel and the difference is also statistically significant. Profits are also significantly different depending on whether farmers participate in famers‟ organization or not. Table 5: Variety variance analysis variety sales channel member organization Between groups Within groups Between groups Within groups of Between groups Within groups SS df MS F Prob>F 3.2648e+10 6 5.4414e+09 13.08 0.0000 2.3759e+11 571 416096976 2.5566e+10 2 1.2783e+10 29.02 0.0000 2.1935e+11 498 440467793 3.3177e+09 1 3.3177e+09 7.03 2.6393e+11 559 472143433 0.0083 4.3 Comparison between New Variety and Traditional Variety We examine whether new variety is superior in terms of their contribution to profit. Suli, Korla, Pingguoli, Mixue and Yali could be viewed as traditional pear varieties, while the rest that are bred by local scientists or imported from foreign countries are viewed as new varieties. Results reported in table 6 demonstrate that new varieties of pear command a significant advantage over their traditional counterpart in pursuing profit objective. Table 6: Profit Results Harvested area Average price yield New variety profit 904.8** (2.61) 10293.7*** (9.09) 585.4*** (8.22) 5770.5** Proceedings of World Business, Finance and Management Conference 14 - 15 December 2015, Rendezvous Grand Hotel, Auckland, New Zealand ISBN: 978-1-922069-91-7 (3.10) Sell by wholesaler 1307.1 (0.61) Sell by organization 5548.5 (1.92) Member of famers‟ organisation 6620.8*** (3.88) New technique 219.3 (0.13) age -210.4* (-2.16) Share of non-farm income 57.47 (1.53) _cons -26713.7*** (-4.12) N 459 t statistics in parentheses * p< 0.05, **p< 0.01, ***p< 0.001 4.4 Random Effect Model Results Random effects models have the advantage in that they can estimate coefficients for explanatory variables that are constant over time. In our survey, these include the variables of pear variety, sales channel and membership to farmers‟ organization. Random effects models also provide more degrees of freedom compared to their fixed effects counterpart as they estimate the parameters that describe the distribution of the intercepts rather than estimating an intercept for virtually every cross-sectional unit. In this model variant, we kept our definition of pear variety same as before. Results reported in Table 7 show profitability of six of the important varieties of pear. In terms of sales channel, selling by firms or organizations bring superior results compared to selling by farmers themselves. The regression results show that area harvested, pear price and yield have significant positive effects on profit. In terms of variety, Huangguan and DuangshanSuli are most profitable. Suli, Korla pear and Huanghua have significantly negative profit coefficient. Farmers achieve significantly more profits by selling via cooperative organizations. Selling to wholesalers has positive effects on profit but not significant. In addition, farmer‟s participation in a cooperative organization is a profitable exercise. Farmers‟ age and larger share of non-farm income has negative effect on profitability, but are not statistically significant. Likewise, adopting new technique raises profitability, but the coefficient is not significant. Beta coefficients are regression results when independent variables‟ value is standardized by subtracting off its mean and dividing by its standard deviation. It will make the scale of the repressors irrelevant and not affect statistical significance. The results (Table 7) show that sales price has the largest standardized effect. A one standard deviation increase in average sales price raises profit per hector by 0.594 standard deviation. The same movement of yield has a larger effect on profit than area harvested. Variety of Proceedings of World Business, Finance and Management Conference 14 - 15 December 2015, Rendezvous Grand Hotel, Auckland, New Zealand ISBN: 978-1-922069-91-7 DangshanSuli and Huangguan has a larger effect on profit than selling by organization or participating in farmers‟ cooperative organization. It means that choosing the “correct” variety is more important than choosing a selling channel or be a member of farmers‟ cooperative organization. Table 7: Random Effect Model Results profit Harvested area 1296.7*** (3.45) Average price 15508.6*** (8.13) yield 617.6*** (7.77) Yali -11062.3 (-1.78) Suli -8881.4** (-2.90) DangshanSuli 16823.4*** (4.41) Korla -20717.5*** (-5.78) Huangguan 11563.1* (2.28) Huanghua -19076.3*** (-5.78) Sell by wholesaler 3478.9 (1.43) Sell by farmers‟ organisation 7198.4* (2.32) Member of farmers‟ organisation 988.0 (0.45) age -217.2 (-1.54) New technique 1319.1 (0.72) Share of non-farm income -35.10 (-0.89) _cons -26223.5*** (-3.30) N 465 t statistics in parentheses * p< 0.05, **p< 0.01, ***p< 0.001 Beta coefficients 0.144*** (3.45) 0.594*** (8.13) 0.413*** (7.77) -0.121 (-1.78) -0.151** (-2.90) 0.158*** (4.41) -0.336*** (-5.78) 0.153* (2.28) -0.175*** (-5.78) 0.076 (1.43) 0.130* (2.32) 0.022 (0.45) -0.073 (-1.54) 0.029 (0.72) -0.044 (-0.89) 465 Proceedings of World Business, Finance and Management Conference 14 - 15 December 2015, Rendezvous Grand Hotel, Auckland, New Zealand ISBN: 978-1-922069-91-7 5. Conclusion Indigenous pears have been cultivated in China for over 2000 years. Currently China stands out as the largest pear producer in the world both in terms of output and acreage. We know that farmers can be technically efficient in terms of maximizing output per input and still remain profit inefficient as the latter requires prudent output mix and marketing abilities. Market deregulations thrown at Chines communes in 1980s meant Chinese farmers were left to face both opportunities and challenges. At the same time new and improved varieties of pear were being released that are either scientifically bred or imported from abroad. Some farmers were willing and able to produce these new, improved varieties while others kept up with the traditional varieties of pear. Impacts of these innovations and opportunities on farmer‟s profit remain an empirical question. By examining the determinants from a standard profit function and applying survey data from Chinese pear farmers, we are able to reach some firm conclusions. Our annual survey conducted on 184 Chinese pear farmers from eight leading pear-producing provinces gave us enough information on pear price, production cost, pear variety and socio-economic variables on which to base our conclusions. We found that acreage harvested, selling price and yield have significant positive effects on the profit, as a standard profit function would dictate. Our coefficient estimates goes a step further to show that sales price has the largest standardized effect on profit and that a same proportionate change in yield has a larger effect on profit than acreage harvested. New varieties of pear command a significant advantage over their traditional counterpart in pursuing profit objective. In terms of sales channel, selling by firms or organizations bring superior results compared to selling by farmers themselves. Overall, we find that choosing the “correct” variety and selling channel are more important than many other perceived determinants of profit. References Ali, M., & Flinn, J. C. 1989 . Profit efficiency among Basmati rice producers in Pakistan Punjab. American Journal of Agricultural Economics, 71(2), 303-310. Anríquez, G., & Valdes, A. 2006 . Determinants of farm revenue in Pakistan. The Pakistan development review, 281-301. Ansoms, A., Verdoodt, A., & Van Ranst, E. 2008 . The inverse relationship between farm size and productivity in rural Rwanda. IOB, University of Antwerp. Block, S., & Webb, P. 2001 . The dynamics of livelihood diversification in post-famine Ethiopia. Food Policy, 26(4), 333-350. Doole, G. J. 2015 . Improving the profitability of Waikato dairy farms: insights from a whole-farm optimisation model. New Zealand Economic Papers, 49(1), 44-61. Proceedings of World Business, Finance and Management Conference 14 - 15 December 2015, Rendezvous Grand Hotel, Auckland, New Zealand ISBN: 978-1-922069-91-7 Evenson, R. E., & Gollin, D. 2003 . Crop variety improvement and its effect on productivity: The impact of international agricultural research: Cabi. Farrell, M. J. 1957 . The measurement of productive efficiency. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society. Series A (General), 253-290. Fischer, E., & Qaim, M. 2012 . Linking smallholders to markets: determinants and impacts of farmer collective action in Kenya. World Development, 40(6), 1255-1268. Hellin, J., Lundy, M., & Meijer, M. 2009 . Farmer organization, collective action and market access in Meso-America. Food Policy, 34(1), 16-22. Lockheed, M. E., Jamison, T., & Lau, L. J. 1980 . Farmer education and farm efficiency: A survey. Economic development and cultural change, 37-76. McNally, S. 2002 . Are „Other Gainful Activities‟ on farms good for the environment? Journal of Environmental Management, 66(1), 57-65. McDonald, R. A., & Schroeder, T. C. 2003 . Fed cattle profit determinants under grid pricing. Journal of Agricultural and Applied Economics, 35(01), 97-106. Nwauwa, L. O. E., Rahji, M. A. Y., & Adenegan, K. O. 2013 . Determinants of Profit Efficiency of Small-Scale Dry Season Fluted Pumpkin Farmers Under Tropical Conditions: A Profit Function Approach. International Journal of Vegetable Science, 19(1), 13-20. doi: 10.1080/19315260.2012.662582 Qasim, M. 2012 . Determinants of Farm Income and Agricultural Risk Management Strategies: The Case of Rain-fed Farm Households in Pakistan's Punjab (Vol. 3): kassel university press GmbH. Tegegne, F., Pasirayi, S., Singh, S. P., & Ekanem, E. P. 2012 . Marketing Channels Used by Small Tennessee Farmers. Journal of Food Distribution Research, 43(1). Tsourgiannis, L., Eddison, J., & Warren, M. 2008 . Factors affecting the marketing channel choice of sheep and goat farmers in the region of east Macedonia in Greece regarding the distribution of their milk production. Small Ruminant Research, 79(1), 87-97. Verhaegen, I., & Van Huylenbroeck, G. 2001 . Costs and benefits for farmers participating in innovative marketing channels for quality food products. Journal of Rural Studies, 17(4), 443-456.