Proceedings of 10th Asia - Pacific Business and Humanities Conference

advertisement

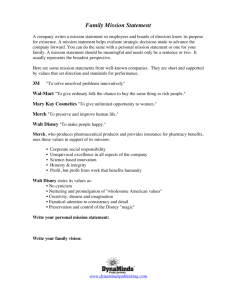

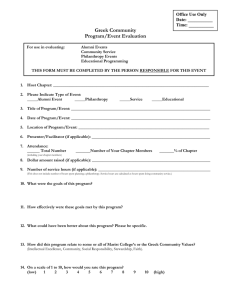

Proceedings of 10th Asia - Pacific Business and Humanities Conference 22 - 23 February 2016, Hotel Istana, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia ISBN: 978-1-925488-00-5 Corporate Philanthropic Behavior among Small and Medium Enterprise (SME) Owners in Malaysia Kishen Tulsidas Adnani*, Ng Siew Imm** and Gan Bee Ching*** SMEs are considered the backbone of a nation’s economy. In Malaysia, they account for almost 90% of all business establishments. However, SMEs have never been at the forefront in their philanthropic initiatives. This study attempts to examine the antecedents of philanthropic behavior among SMEs in Malaysia by presenting a holistic framework using the Theory of Planned Behavior as its underlying theoretical base. Using a mixed-methods research design, semi-structured interviews will be conducted with SME owners, non-profit organizations (NPOs) and government agencies. This will be followed by a survey among SME owners. The findings of this study will assist NPOs in soliciting donations from SME owners. JEL Codes: 1. Introduction Philanthropy is not a new phenomenon as it has been in existence since the 16th century (Adam, 2004). The term originates from an ancient Greek word that means “love of humanity” (Downey, 1955) whereby people helped others purely out of love and compassion. In the business environment today, corporate philanthropy is the act of sacrificing money, assets, time or effort to benefit others (Acs and Desai, 2007; Burlingame and Young, 1996; Gautier and Pache, 2013). Unlike individual charitable acts, philanthropy is more institutional in nature. There is no direct interaction between the donor and the actual recipient (Woods, 2006; Bekkers and Wiepking, 2010). The beneficiaries of philanthropy are mostly non-profit organizations (NPOs). The term “corporate philanthropy” leads to the misconception that only large corporations are involved in philanthropy. Instead, it is also widespread among SMEs (Gautier and Pache, 2013). This comes as no surprise as SMEs account for more than half of the employment and a substantial share of the GDP of most countries (Baumann-Pauly, Wickert, Spence and Scherer, 2013). In Malaysia, SMEs account for 98.5% of all business establishments, employing around 65% of the work force (Bank Negara Malaysia Report, 2013). They also contributed about 32% of the GDP in 2010 (SMECORP, 2012). However, there is a mismatch between the philanthropic contributions made by SMEs and their overall number of establishments. There are evidences of charitable giving in the context of the United States to illustrate this mismatch. According to the Giving USA Foundation 2014 Report (cited in Watson, 2014), individualgiving constitute around 72% of total contributions to NPOs. Another 15% is contributed by privately-held foundations. Corporations constitute only 5% of total giving in the United *Kishen Tulsidas Adnani, Faculty of Business, Economics and Accounting, HELP University, Malaysia. Email : kishenta@help.edu.my **Dr. Ng Siew Imm, Department of Management and Marketing, Universiti Putra Malaysia Email: imm_ns@upm.edu.my ** Dr. Gan Bee Ching, ELM Graduate School, HELP University, Malaysia Email: gan.beeching@help.edu.my 1 Proceedings of 10th Asia - Pacific Business and Humanities Conference 22 - 23 February 2016, Hotel Istana, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia ISBN: 978-1-925488-00-5 States (Watson, 2014). A similar pattern is also observed in the United Kingdom, Australia and Malaysia (Brammer and Pavelin, 2005; Smith and McSweeney, 2007, Top10Malaysia Online). In Malaysia, owners of large corporations are the biggest philanthropists, but they usually donate in their personal capacity (Top10Malaysia Online). Thus, philanthropy among SMEs in Malaysia warrants a study to understand the causes of this mismatch. Unlike large corporations, SMEs have a smaller scale of operations and face resource constraints (Udayasankar, 2007). Therefore, the extant literature on corporate philanthropy mainly examines the drivers among large corporations (Gautier and Pache, 2013; Bekkers and Wiepking, 2010; Dennis, Buchholtz and Butts, 2007; Lahdesmaki and Takala, 2012). In large corporations, the drivers for corporate philanthropy are mostly firm-level constructs. CEOs of such corporations may be restricted by company policies on the type of social issues and allocations (Hemingway and Maclagan, 2004). On the other hand, philanthropic initiatives by SMEs that are owner-managed are influenced by the owners’ personal beliefs and values. Furthermore, most of the studies on philanthropy have been carried out in the United States and Europe, leading to a dearth of literature on philanthropy from the Asian perspective. Asian societies are characterized as collectivist, as opposed to the individualist societies found in the West. In a collectivist society, the “ties between individuals are very tight”; and members of a community are supposed to look after the interest of each other (Hofstede, 1983). Thus, a study on the various drivers of philanthropic behavior in the Asian context is warranted. The main objective of this study is to develop a holistic framework that would be able to explain philanthropic behavior among SMEs in the Malaysian context. 2. Literature Review Philanthropy is the voluntary facet of corporate social responsibility (CSR) which spans over and above an organization’s economic, legal and ethical responsibilities (Carroll, 1999, see Figure 1 below). The idea of “social responsibility” was first mooted by Howard R. Bowen in his seminal publication Social Responsibilities of the Businessman in 1953 (Bowen, 2013). However, the concept of organizations being altruistic goes against the principles of neoclassical economics theories. Adam Smith, the founder of the modern economics, propagated that society is best served by individuals pursuing their self-interest (Smith in Gabbard and Atkinson, 2007). Echoing his thoughts, economists such as Friedman (1970) argued that philanthropy was redundant and illegitimate due to the unwarranted financial burden it posed on corporations. Profit-seeking organizations had “no business dabbling in social causes” (Friedman, 1970). However, most governments now are burdened with huge deficits; and growing social issues (Gautier and Pache, 2013). CSR is the result of the lack of regulation & government incapacity to champion all social issues (Benabou and Tirole, 2009). Since businesses do not exist in vacuum; business owners have responsibilities towards the society. 2 Proceedings of 10th Asia - Pacific Business and Humanities Conference 22 - 23 February 2016, Hotel Istana, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia ISBN: 978-1-925488-00-5 Figure 1 Corporate Social Responsibility Model (Source: Carroll, 1999) Individual charitable giving and corporate philanthropy have been studied through several distinct academic disciplines that include: management, sociology, psychology, economics, marketing, and public policy (Gautier and Pache, 2013; Bekkers and Wiepking, 2010). However, philanthropic acts are usually the result of multiple mechanisms working simultaneously (Bekkers and Wiepking, 2010). As a result of studying philanthropy through distinct fields, philanthropy lacks an integrative model. Daly (2012) argues that the lack of an integrated framework has left the concept, scope and practice of corporate philanthropy highly contested. For instance, Gautier and Pache (2013) argue that corporate philanthropy can be placed on a continuum for three rationales: (i) genuine commitment for common good (ii) long-term community investment, and (iii) marketing approach. It is not clear which of these three motivators drive philanthropic behavior among SMEs. Despite their vast economic contribution, research on the philanthropic behavior of SMEs has been sidelined. Any attempt to examine philanthropy among SMEs must consider individual and firm drivers as well, since most SMEs are owner-managed. 2.1 Non-Profit Organizations and Philanthropy in Malaysia Apart from the private and public sectors, there is another sector which is known for its notfor-profit missions. This voluntary sector is also known as the Third Sector (Morris, 2000). It consists of non-profit organizations (NPOs). In the United States, philanthropy is actively indulged by both individuals and corporations. Corporations in the United States tend to donate extensively as they are able to save millions in taxes because most NPOs are given tax-exempt status (Top10Malaysia Online). In Malaysia, it is the individual business leaders that stand out as the biggest philanthropists (Top10Malaysia Online). This is because most of the wealthiest companies in Malaysia are controlled by individuals or families. However, they prefer to make personal contributions instead, to avoid shareholders’ displeasure (The Star Online, 2012). 3 Proceedings of 10th Asia - Pacific Business and Humanities Conference 22 - 23 February 2016, Hotel Istana, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia ISBN: 978-1-925488-00-5 The philanthropic landscape in Asia differs from Western countries in several ways (Ton, 2014). Firstly, philanthropy in Asia tends to focus on short-term results. This can be a challenge for NPOs that require long-term funding. Secondly, there are minimal collaborations between businesses and NPOs in Asia. This is partly because many business owners still expect the government to take full responsibility of the people’s welfare. Finally, on a positive note, the desire to give back to society is the main reasons for philanthropy. This is an indicator that individuals and businesses want to take charge in building their communities (Ton, 2014). Most CSR studies in Malaysia focused on its CSR disclosure; giving less prominence to its awareness and perception. Furthermore, the emphasis has been on public-listed companies and subsidiaries of foreign-owned companies (Nasir et al, 2015). Ismail and Alias (2013) presented a conceptual framework that attempts to explain Islamic philanthropy (zakat) that is compulsory for all Muslims. Several other studies were carried out to examine CSR motivations among SMEs (Nejati and Amran, 2009), CSR initiatives (Amran and Nejati, 2012), ethical practices among entrepreneurial ventures (Ahmad and Ramayah, 2012), CSR practices among telecommunications companies and their enlightened self-interest in CSR (Mohamed and Sawandi, 2007), and the roles and attitudes of CSR-compliant companies (Ismail et al, n.d.). Through a series of preliminary reviews, Cogswell (2002) made several observations about philanthropy in Malaysia. Firstly, it is difficult to judge its full extent and impact, as the relevant governmental bodies do not gather sufficient data. Secondly, despite being a multicultural society, most philanthropic initiatives are ethnic specific, and they are meant for the donor’s cultural or religious preservation. According to Amran et al (2013), the Malaysian government needs to help empower local communities into legitimate and powerful stakeholders. This is because CSR is still in its infancy stage in Malaysia. Singh, Islam and Ariffin (2015) proposed a conceptual framework comprising several drivers of philanthropic CSR among SMEs. These include: intra-organizational factors, competitive dynamics, institutional investors, customers, government regulators, and the role of NGOs. 2.2 Philanthropic Behavior and its Relevance in the SME Context SMEs are considered the backbone of every nation’s economy as they provide more than half of employment and a significant share of the country’s GDP (Baumann-Pauly et al, 2011). In Malaysia, SMEs in the manufacturing sector have less than 200 employees or an annual sales turnover not exceeding RM50 million. As for the service sector, SMEs are enterprises with 75 or less full-time employees or annual sales turnover not exceeding RM20 million (SMECORP, 2012). In 2013, Malaysian SMEs accounted for around 98.5% of all business establishments, employing 5.6 million (around 65%) of the national work force (Bank Negara Malaysia Website). SMEs also contributed about 32% of the GDP in 2010 (SMECORP, 2012). Despite the sizable work force and economic contribution of SMEs, CSR research has always been focused on large multinational corporations MNCs (Lepoutre and Heene, 2006). According to Gautier and Pache (2013), philanthropy is not only widespread among MNCs but it is also dominant among SMEs across the globe. For instance, in a qualitative research carried out among Swiss MNCs and SMEs, Baumann-Pauly et al (2011) found that the SMEs were at par with the MNCs in their CSR commitment. They also concluded that 4 Proceedings of 10th Asia - Pacific Business and Humanities Conference 22 - 23 February 2016, Hotel Istana, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia ISBN: 978-1-925488-00-5 SMEs were better off than MNCs in implementing CSR initiatives. However, MNCs have better formal reporting mechanisms than SMEs; and this has often led to the misconception that SMEs are not committed their CSR endeavor (Baumann-Pauly et al, 2011). Furthermore, large corporations have been at the forefront to tackle global issues. These include: labor standards, climate change, and human rights issues (Rasche and Kell, 2010). Such CSR initiatives are commonly carried out by large corporations as they have the necessary human and financial resources. On the other hand, smaller firms are more influenced by the general value system within the communities they operate (Lepoutre and Heene, 2006). 2.3 Theories Explaining Philanthropic Behavior Corporations may be motivated to engage in philanthropic behavior for two distinct reasons: self-interest or pure altruism (Garriga and Mele, 2004). Burlingame and Young (1996) were some of the first scholars to examine the drivers behind corporate philanthropy. They categorized philanthropy into four distinct groups of models: (i) The neoclassical productivity model – philanthropy is part of the main objective of profit maximization; (ii) The altruistic model – corporations who genuinely contribute towards social causes; (iii) The political model – philanthropic involvements are means to obstruct government interference in private businesses; and (iv) The stakeholder model – corporations try to work out a compromise between divergent stakeholder interests. The stakeholder theory warrants that every action which an organization takes, it must put into consideration the legitimate interests of its stakeholders (Donaldson and Preston, 1995). The central tenet of this theory is that corporations are expected to satisfy a number of stakeholder groups; and not its shareholders alone. These groups include: employees, customers, suppliers, competitors, and communities in which the corporation operates (Campbell, 2007). Therefore, corporations need to reassess their achievement of traditional objectives such as profitability and growth alone (Donaldson and Preston, 1995). This close link between stakeholder theory and CSR is supported through a study on 400 firms in the United States and Europe to identify the factors that motivate CSR initiatives (Maignan and Ralston, 2002). They found that the top three motivations for behaving in socially responsible manner were: (1) The managers valued such behavior (normative); (2) The managers believed that it enhanced the financial performance of their firms (instrumental); and finally, (3) the stakeholders expected them to behave like this. The prosocial behavior theory is defined as any behavior meant to benefit others. Such behaviors include: volunteering time, helping strangers, giving to charitable organizations, donating blood, and even risking one’s life for strangers (Benabou and Tirole, 2005). According to Carlo and Randall (2002), helping behavior is usually intrinsically motivated by altruism or empathic feelings. However, it can also be driven by external factors such as gaining recognition or approval from others. Hence, they identified six drivers of prosocial behaviors: altruistic, compliant, emotional, dire, public, and anonymous. 5 Proceedings of 10th Asia - Pacific Business and Humanities Conference 22 - 23 February 2016, Hotel Istana, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia ISBN: 978-1-925488-00-5 The altruistic prosocial behavior refers to actions carried out primarily by the concern and welfare of others; such that individuals may be demotivated if offered external rewards. Compliant prosocial behaviors are defined as helping others only when solicited; whilst public prosocial behaviors are those that are conducted in front of others to meet self-serving purposes as well. Anonymous prosocial behaviors are helping actions that are performed without the knowledge of the person that is helped (Carlo and Randall, 2002). NPOs make ample use of donors’ desire for publicity by rewarding them with “perks” such as media coverage, awards or certificates. Such prosocial behavior becomes instrumental for enhanced social esteem. The social capital theory also helps explain philanthropic behavior. Social capital is the networks and common norms of reciprocity that members of a community or society share. As a form of capital, members find some value by being part of these social networks (Putnam, 2001; Lin, 1999). Examples of social capital include: a formal trade association, clubs, regular churchgoers, labor union, or an informal bowling group. Members of such groups develop a sense of reciprocity among themselves. Members of communities that were close-knit looked into the well-being of one another (Putnam, 2001). For instance, through such networks, wealthy members of a community donate towards other needy members. This is usually common among collectivist communities with strong cultural identities (Lin, 1999). 2.4 Empirical Studies and Models of Philanthropic Behavior The Theory of Reasoned Action (TRA) and its extension, Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB) are two of the most influential conceptual frameworks for the study of human behavior. These theories focus on theoretical constructs concerned with individual motivational factors as antecedents of performing a specific behavior (Montano et al, 2008). Both TRA and TPB assume the best predictor of a behavior is behavioral intention. According to the TRA, intention itself is the result of two predictors: one’s attitude to engage in the behavior and the subjective norms surrounding the behavior (Ajzen and Fishbein (1980). The TRA is grounded in the assumption that a closer association between attitude and behavior is likely to be found if intention is used as a mediator. However, despite having a strong attitude, and favorable subjective norms, the ability to engage in that behavior may be inhibited by additional personal and situational factors (Ajzen, 2002). This led to the development of the TPB which had a third predictor: perceived behavioral control (PBC); which was meant to improve the predicting power of the TRA. In short, the TPB encompasses five specific constructs: attitudes, subjective norms, PBC, behavioral intention and the actual behavior itself. This is illustrated in Figure 2 below. However, TPB models are open to further expansion as and when additional predictors are identified (Ajzen, 1991). 6 Proceedings of 10th Asia - Pacific Business and Humanities Conference 22 - 23 February 2016, Hotel Istana, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia ISBN: 978-1-925488-00-5 Figure 2.2 Theory of Planned Behavior (Source: Ajzen, 2002) Numerous studies have been carried out using TPB to explain many types of behavioral intentions and behaviors. These include quitting to smoke, drinking, health services utilization, exercising, HIV/STD-prevention behaviors and use of safety helmets, and seatbelts (e.g. Montano et al, 2008; Astrom & Rise, 2001; Conner, Norman, & Bell, 2002; McMillan & Conner, 2003). Behavioral intention is defined as a disposition to act (Ajzen, 1999). It is a composition of many motivational factors that influence behavior. Behavioral intention is considered the key psychological factor that differentiates reasoned from nonreasoned behavior (Bagozzi and Yi, 1989). Behavioral intention is an indicator of an individual’s readiness to perform a given behavior, and therefore, it is an immediate antecedent of behavior. The antecedents of intention are attitude, subjective norms and PBC. Ajzen and Fishbein (1980) define attitude as an individual’s psychological evaluation of an element or object. An attitude is formed when individuals associate certain positive or negative value or belief of the said behavior. Subjective norms (SN) are the perceived social pressure and the normative expectations that people have on an individual (Ajzen, 2002). This internally-controlled perception pressures individuals to behave in a certain way as they try to seek the approval from their referent groups. Finally, PBC is an individual’s perceptions of the ease or difficulty of performing a certain behavior (Ajzen, 2002). According to Fini et al (2012), PBC is developed from the internal beliefs that an individual holds about the presence of resources and opportunities for a particular behavior. In an attempt to study the determinants of philanthropic behavior, Dennis et al (2007) used TPB as its underlying theoretical foundation. This study was conducted among 84 CEOs of large corporations in the United States. Their model was built by incorporating two distinct perspectives of philanthropy: strategic philanthropy and altruistic philanthropy. It empirically examined the effects of the following antecedents: economic attitude, PBC, political pressure, moral obligation, and self-identity. Slack (excess funds) was examined as a moderator between these drivers and the actual philanthropic behavior. However, this model poorly explained the variance in the determinants for corporate philanthropy. Only the role of CEO self-identity was found to positively explain the philanthropy initiatives carried by 7 Proceedings of 10th Asia - Pacific Business and Humanities Conference 22 - 23 February 2016, Hotel Istana, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia ISBN: 978-1-925488-00-5 these corporations (Dennis et al, 2007). However, it concluded that there were many other drivers that could explain philanthropy. Similarly, Smith and McSweeney (2007) used a revised TPB model to investigate the patterns of charitable giving among Australians. They believed that attitude, social norm (SN) and PBC alone cannot adequately explain charitable giving. Therefore, several other socio-physiological predictors were added to their model. These include: injunctive norms (what people expect you to do), descriptive norms (what others actually did), and personal injunctive moral norms (what you must do based on your personal feelings). Past behavior was also added as an antecedent. This longitudinal study found that attitude, PBC, injunctive norms, moral norms, and past behavior were strong predictors of charitable giving intentions among Australians. However, descriptive norms and past behavior were not able to explain donating intentions (Smith and McSweeney, 2007). The donating intention was a very strong predictor of the actual donating behavior. 2.5 Drivers of Philanthropic Behavior Despite being clearly defined as unconditional and non-reciprocal; the motives underpinning corporate philanthropy remains debatable (Gautier and Pache, 2013). In numerous large corporations, philanthropy has been carefully designed to fit its long-term goals. This notion of using philanthropy for self-serving purposes has become so widespread that the term “strategic philanthropy” was coined to gauge its effectiveness (Sanchez, 2000; Valor, 2006). This concept is commonly assumed in large corporations that are answerable to shareholders and board of directors. Varadarajan and Menon (1998) found evidence of organizations that use philanthropy as a marketing tool. This gave rise to the concept of "enlightened self-interest" which examines philanthropy from an investment point of view. However, this does not mean that all corporations have some form of self-interest in their philanthropic pursuits. Valor (2006) researched the patterns of giving among corporations and concluded that pure altruistic intention is one of the main drivers of philanthropy. Bekkers and Wiepking (2011) identified eight mechanisms that drive charitable giving: awareness of need, solicitation, costs and benefits, altruism, reputation, psychological benefits, values, and efficacy. However, Bekkers and Wiepking (2011) also concluded that there could be “numerous systematic patterns in the mix of these mechanisms and the interactions among them”. Drivers of philanthropy are always examined at the three distinct levels: individual, organizational (firm), and national (Rupp, Williams and Aguilera, 2011). Most research on philanthropy has been carried out on large corporations. This is because SMEs have not been at the forefront in their philanthropic initiatives. For smaller businesses, philanthropic initiatives may be based on a variety of other potential motives (Sanchez, 2000). These motivations are more personal in nature, and much more diverse when compared with large businesses (Sanchez, 2000). The following drivers have been highlighted in the extant literature as significant predictors. Individual SME owners in the Asian and Western cultural context may share similar values. Findings from the Western context reported altruism, moral obligation, and religiosity influence philanthropic behavior (Batson and Shaw, 1991; Wulfson, 2001; Park and Smith, 2000). Altruism is defined as the empathic feelings and concern that an individual has over another person which evokes actions that benefit the other person (Lahdesmaki and Takala, 2012, Batson and Shaw, 1991). In the case of corporate philanthropy, Sanchez (2000) 8 Proceedings of 10th Asia - Pacific Business and Humanities Conference 22 - 23 February 2016, Hotel Istana, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia ISBN: 978-1-925488-00-5 points out that altruism is independent of any strategic pressure of generating profits or creating goodwill. Moral obligation is defined as the personal feelings of responsibility to carry or not carry out certain acts (Ajzen, 1991). It strongly correlates with intentions to behave within ethical dimensions, which is guided by ethics and its rational determination to do what the actor thinks is right (Wulfson, 2001). Religiosity is a belief in a higher spiritual being (Park and Smith, 2000); and it has a positive impact on prosocial behavior. Regardless of which religion an individual believes in, the religiosity aspect of all religions is consistent (Granger et al, 2014); and it consists of the following core aspects: a strong belief in some form of Supreme Being, God or supernatural forces, a set of common doctrines, and the attendance at formalized worships. Trust is the belief that the trustee will act cooperatively to fulfill the trustor’s expectations without exploiting its vulnerabilities (Luhmann in Pavlou and Fygenson, 2006). Most donors would want to study the NPO and the social causes it champions. Over and above that, potential donors would like to assess its performance, the transparency of its management, and the benefits it provides to society (Sargeant et al, 2006). This is because there is a tendency for misappropriation of funds and exploitation in the voluntary sector (Jones, Wilikens, Morris, and Masera, 2000). At the firm-level, philanthropic decisions are influenced by two other drivers: tax relief and strategic philanthropy. Tax relief refers to the discounts given by the government to individuals and corporations for donations (Lyons and Passey, 2006). Tax exemptions are awarded to NPOs that champion social causes deemed worthwhile by the government (Blumkin and Sadka, 2007). For a very long time, many Western countries have permitted tax relief for gifts to certain NPOs that champion social causes deemed worthwhile. Tax incentives for philanthropy are part of the fiscal policy measures that cannot be easily removed by their respective government (Lyons and Passey, 2006). The concept of “strategic philanthropy” (Porter and Kramer, 2006), allows business owners to choose philanthropic initiatives that suit long-term objectives of their businesses.The notion of using corporate philanthropy for self-interest sharply contrasts with its original idea of altruism. Nevertheless, corporations do look out for value added charitable giving with creative strategies that are able to produce maximum benefits (Mullen, 1997). Recognition is associated with public prosocial behavior. Such actions are carried out in the presence of others; and they are meant to meet self-serving purposes (Carlo and Randall, 2002). Most individuals are motivated by some form of recognition. In many cases, donations are pledged only when donors are promised with some associated benefits (Grace and Griffin, 2006). Solicitation is a request for donations or volunteerism from an individual or corporation, made by any NPO directly or through its members. In a study on philanthropic behavior among large corporations, Werbel and Carter (2002) found a strong link between CEOs’ personal affiliations with an NPO and the charitable programs they supported. This is because NPOs would find it easier to solicit donations if they knew someone in that organization. 9 Proceedings of 10th Asia - Pacific Business and Humanities Conference 22 - 23 February 2016, Hotel Istana, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia ISBN: 978-1-925488-00-5 3. Conceptual Model The conceptual framework for this study is presented in Figure 3 below. It draws on the TPB as its underlying theoretical foundation. As a collectivistic society, some of the antecedents that explain philanthropic behavior among SMEs in Malaysia may differ from the Western context. The variables, as discussed above, emerged from the extant literature. The moderating effect of recognition and solicitation on the relationship between philanthropic intention and philanthropic behavior will also be tested in this study. In the Malaysian context, recognition and solicitation are likely to moderate the relationship between philanthropic intention and philanthropic behavior. Since Malaysian culture emphasizes face-saving (Abdullah, 1996), recognition may enhance the possibility of converting intentions to philanthropic behavior. The Malaysian culture also has a strong sense of social sensitivity along with feeling of guilt and shame. It emphasizes harmonious relationships with significant others in their lives (Abdullah, 1996). As a result, individuals are more willing to sacrifice personal interests for the sake of collectivistic wellbeing. Therefore, solicitations by close acquaintances would lead to philanthropic behavior among individuals with prior philanthropic intentions. The present study will also incorporate two more variables that have not been previously examined. These predictors are causation and communality. Causation is defined as the belief that an individual has on the future effects of his or her present actions. Therefore, this principle of cause and effect drives individuals to carry out prosocial acts (Mulla and Venkat, 2006). This belief is consistent with Potter’s (1964) prescriptive theory of causation which is meant to compel or restrain people from acting in certain ways. Drawn from social capital theory (Putnam, 2001), communality is the feeling of kinship that members of closeknit communities share among themselves. The benefits that SMEs derive from the local community may be reciprocated through philanthropic initiatives back to the community. The hypotheses drawn up for this study are presented in Table 1 below. 10 Proceedings of 10th Asia - Pacific Business and Humanities Conference 22 - 23 February 2016, Hotel Istana, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia ISBN: 978-1-925488-00-5 Table 1 Hypotheses Developed for this Study H1: There is a positive relationship between Attitude towards philanthropy and Philanthropic Intention. H2: There is a positive relationship between Subjective Norms on Philanthropy and Philanthropic Intention. H3: There is a positive relationship between Perceived Behavioral Control on philanthropy and Philanthropic Intention. H4: There is a positive relationship between Tax Relief offered by the government and Philanthropic Intention. H5: There is a positive relationship between Strategic Philanthropy and Philanthropic Intention. H6a: There is a positive relationship between Altruism and Attitudes towards Philanthropy. H6b: There is a positive relationship between Moral Obligation towards surrounding communities and Attitudes towards Philanthropy. H6c: There is a positive relationship between Causation beliefs and Attitudes towards Philanthropy. H6d: There is a positive relationship between Religiosity and Attitudes towards Philanthropy. H6e: There is a positive relationship between Trust in NPOs and Attitudes towards Philanthropy. H7: There is a positive relationship between feelings of Communality and Subjective Norms on Philanthropy. H8: There is a positive relationship between Philanthropic Intention and Philanthropic Behavior. H9: The relationship between Philanthropic Intention and Philanthropic Behavior will be moderated by Recognition, such that this relationship will be stronger when SME owner-managers receive recognition for their contributions. H10: The relationship between Philanthropic Intention and Philanthropic Behavior will be moderated by Solicitation, such that this relationship will be stronger when SME owner-managers receive solicitation from acquaintances. 11 Proceedings of 10th Asia - Pacific Business and Humanities Conference 22 - 23 February 2016, Hotel Istana, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia ISBN: 978-1-925488-00-5 Figure 3 Proposed Conceptual Framework of Drivers of Corporate Philanthropic Behavior among SMEs in Malaysia Altruism Moral Obligation Causation Attitudes towards Philanthropy Religiosity Recognition Trust Communality Subjective Norm Perceived Behavioral Control Philanthropic Intention Philanthropic Behavior Solicitation Taxation Strategic Philanthropy 4. Methodology This study will adopt a mixed-methods research design, using both qualitative and quantitative methodologies in order to achieve the objectives of this study. This study relies on the triangulation of qualitative methods (i.e. semi-structured interviews) with quantitative methods (i.e. survey questionnaire). Hence, the initial qualitative phase involves semistructured interviews with NPOs, government agencies and SMEs. These interviews are meant to determine the level of philanthropic involvement and the social causes championed by SMEs in Malaysia. Most importantly, its purpose is to derive the main themes that can adequately explain the philanthropic behavior among SMEs in Malaysia. The subsequent quantitative method is employed to test the empirical model, and hypotheses developed above. For this purpose, a questionnaire survey will be personally administered among SME owner-managers. This questionnaire will also be translated from English to Bahasa Melayu and Mandarin to cater for respondents that were educated in national or Chinese schools. The unit of analysis for this study is the SME owner-manager. According to the SMECORP Guideline (2012), organizations in Malaysia are categorized 12 Proceedings of 10th Asia - Pacific Business and Humanities Conference 22 - 23 February 2016, Hotel Istana, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia ISBN: 978-1-925488-00-5 according to their number of employees and annual sales. In Malaysia, SMEs in the manufacturing sector have less than 200 employees or an annual sales turnover not exceeding RM50 million. For organizations in the service sector, SMEs have 75 or less fulltime employees or annual sales turnover not exceeding RM20 million (SMECORP Guideline, 2012). In 2013, Malaysian SMEs accounted for around 98.5% of all business establishments (Bank Negara Malaysia Website). Since the target population for this study is the SMEs in Malaysia, this study will use the SMECORP directory. Almost one-third of the SMEs are based in Selangor (19.5%) and Kuala Lumpur (13.1%). Using the cluster sampling technique, this study will randomly pick establishments from these two physically close clusters. Sekaran (2003) recommends a sample size of 384 for studies with a population between 75,000 and 1,000,000 units. Hence, a total of 384 SME owners is the desired sample size for this study. 5. Discussion and Conclusion The main objective of this study is to articulate a holistic model that would be able to explain philanthropic behavior among SMEs in the Malaysian context. It is an attempt to answer the calls by Bekkers and Wiepking (2011) for more research on the drivers of philanthropy at the individual and firm levels. Since most SMEs are owner-managed, the drivers of philanthropy have to be a combination of firm and individual level variables. SME owner‐ managers are able to bring their personal attitudes and values to influence their business decisions, unlike managers in large corporations. Various drivers from the Western and Asian context have been identified from the extant literature. This study hopes to make several theoretical contributions. Firstly, it will expand the explanatory capability of the TPB in the area of philanthropy. The proposed framework extends the original TPB model by incorporating several antecedents and moderating variables that may better explain philanthropic behavior. Secondly, it will present a holistic framework to explain philanthropic behavior among SMEs in Malaysia. Finally, this study will fill the gap on the dearth of literature on philanthropy in the Asian context, by examining the explanation power of two predictors: causation and communality. As for its practical contribution, NPOs in Malaysia will be able to increase their success rate of soliciting donations from SME owners. As such, NPOs must have an insight of the philanthropic behavior of SME owner-managers. This study will be able to uncover the type of social causes championed by SMEs and their underlying motives for supporting them. References Abdullah, A. 1996. Going glocal: Cultural Dimensions in Malaysian Management. Malaysian Institute of Management. Acs, Z. J., & Desai, S. 2007. Democratic capitalism and philanthropy in a global economy. Jena Economic Research Paper. Adam, T. (Ed.). 2004. Philanthropy, patronage, and civil society: experiences from Germany, Great Britain, and North America. Indiana University Press. 13 Proceedings of 10th Asia - Pacific Business and Humanities Conference 22 - 23 February 2016, Hotel Istana, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia ISBN: 978-1-925488-00-5 Ahmad, N. H., & Ramayah, T. 2012. Does the Notion of ‘Doing Well by Doing Good’Prevail Among Entrepreneurial Ventures in a Developing Nation?. Journal of business ethics, 106(4), 479-490. Ajzen, I. 1991. The theory of planned behavior. Organizational behavior and human decision processes, 50(2), 179-211. Ajzen, I. 2002. From intentions to actions: A theory of planned behavior (pp. 665-683). Springer Berlin Heidelberg. Ajzen, I., & Fishbein, M. 1980. Understanding attitudes and predicting social behaviour. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall. Amran, A., & Nejati, M. 2012. Social responsibility of malaysian small businesses: Does it influence firm image?. International Journal of Arts and Sciences, 5(2), 49-59. Amran, A., Zain, M. M., Sulaiman, M., Sarker, T., & Ooi, S. K. 2013. Empowering society for better corporate social responsibility (CSR): The case of Malaysia. Kajian Malaysia, 31(1), 57-78. Astrom, A. N., & Rise, J. 2001. Young adults’ intentions to eat healthy food: Extending the theory of planned behaviour. Psychology and Health, 16, 223-237. Bagozzi, R. P., & Yi, Y. 1989. The degree of intention formation as a moderator of the attitude-behavior relationship. Social Psychology Quarterly, 266-279. Bank Negara Malaysia, Economic and Financial Data for Malaysia, viewed 3 December, 2014, <www.bnm.gov.my/>. Batson, C. D., & Shaw, L. L. 1991. Evidence for altruism: Toward a pluralism of prosocial motives. Psychological Inquiry, 2(2), 107-122. Baumann-Pauly, D., Wickert, C., Spence, L. J., & Scherer, A. G. 2013. Organizing corporate social responsibility in small and large firms: Size matters. Journal of business ethics, 115(4), 693-705. Bekkers, R., & Wiepking, P. 2010. A literature review of empirical studies of philanthropy: Eight mechanisms that drive charitable giving. Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly. Benabou, R., & Tirole, J. 2005. Incentives and prosocial behavior (No. w11535). National Bureau of Economic Research. Blumkin, T., & Sadka, E. 2007. A case for taxing charitable donations. Journal of Public Economics, 91(7), 1555-1564. Bowen, H. R. 2013. Social responsibilities of the businessman. University of Iowa Press. Brammer, S., & Pavelin, S. 2005. Corporate community contributions in the United 14 Proceedings of 10th Asia - Pacific Business and Humanities Conference 22 - 23 February 2016, Hotel Istana, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia ISBN: 978-1-925488-00-5 Kingdom and the United States. Journal of Business Ethics, 56(1), 15-26. Burlingame, D., & Young, D. R. (Eds.). 1996. Corporate philanthropy at the crossroads. Indiana University Press. Campbell, J. L. 2007. Why would corporations behave in socially responsible ways? An institutional theory of corporate social responsibility. Academy of management Review, 32(3), 946-967. Carlo, G., & Randall, B. A. 2002. The development of a measure of prosocial behaviors for late adolescents. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 31(1), 31-44. Carroll, A. B. 1999. Corporate social responsibility evolution of a definitional construct. Business & society, 38(3), 268-295. Cogswell, E. A. 2002. Private philanthropy in multiethnic Malaysia. Macalester International, 12(1), 13. Conner, M., Norman, P., & Bell, R. 2002. The theory of planned behaviour and healthy eating. Health Psychology, 21, 195-201. Dennis, B. S., Buchholtz, A. K., & Butts, M. M. 2007. The nature of giving: A theory of planned behavior examination of corporate philanthropy. Business & Society. Donaldson, T., & Preston, L. E. 1995. The stakeholder theory of the corporation: Concepts, evidence, and implications. Academy of management Review, 20(1), 6591. Downey, G. 1955. Philanthropia in Religion and Statecraft in the Fourth Century after Christ. Historia: Zeitschrift fur Alte Geschichte, 199-208. Fini, R., Grimaldi, R., Marzocchi, G. L., & Sobrero, M. 2012. The determinants of corporate entrepreneurial intention within small and newly established firms. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 36(2), 387-414. Friedman, M. 1970. The Social Responsibility of Business is to Increase its Profits. The New York Times Magazine, September 13. Gabbard, D., & Atkinson, T. 2007. Stossel in America: A case study of the neoliberal/neoconservative assault on public schools and teachers. Teacher Education Quarterly, 85-109. Garriga, E., & Melé, D. 2004. Corporate social responsibility theories: mapping the territory. Journal of business ethics, 53(1-2), 51-71. Gautier, A., & Pache, A. C. 2013. Research on corporate philanthropy: A review and assessment. Journal of Business Ethics, 1-27. 15 Proceedings of 10th Asia - Pacific Business and Humanities Conference 22 - 23 February 2016, Hotel Istana, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia ISBN: 978-1-925488-00-5 Grace, D., & Griffin, D. 2006. Exploring conspicuousness in the context of donation behaviour. International Journal of Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Marketing, 11(2), 147-154. Granger, K., Lu, V. N., Conduit, J., Veale, R., & Habel, C. 2014. Keeping the faith! Drivers of participation in spiritually-based communities. Journal of Business Research, 67(2), 68-75. Hemingway, C. A., & Maclagan, P. W. 2004. Managers' personal values as drivers of corporate social responsibility. Journal of Business Ethics, 50(1), 33-44. Hofstede, G. 1983. The cultural relativity of organizational practices and theories. Journal of international business studies, 75-89. Ismail, M., & Alias, S. 2013 Conceptualizing Philanthropic Behavior and its Antecedents of Volunteers in Health Care. Ismail, M., Kassim, M. I., Amit, M. R. M., & Rasdi, R. M. Roles, Attitudes, and Competencies of Managers of CSR-Implementing Companies in Malaysia. Jones, S., Wilikens, M., Morris, P., & Masera, M. 2000. Trust requirements in e-business. Communications of the ACM, 43(12), 81-87. Lahdesmaki, M., & Takala, T. 2012. Altruism in business-An empirical study of philanthropy in the small business context. Social Responsibility Journal, 8(3), 373388. Lepoutre, J., & Heene, A. 2006. Investigating the impact of firm size on small business social responsibility: A critical review. Journal of business ethics, 67(3), 257-273. Lin, N. 1999. Building a network theory of social capital. Connections, 22(1), 28-51. Lyons, M., & Passey, A. 2006. Need public policy ignore the third sector? Government policy in Australia and the United Kingdom. Australian Journal of Public Administration, 65(3), 90-102. Maignan, I., & Ralston, D. A. 2002. Corporate social responsibility in Europe and the US: Insights from businesses' self-presentations. Journal of International Business Studies, 33(3), 497-514. McMillan, B., & Conner, M. 2003. Using the theory of planned behavior to understand alcohol and tobacco use in students. Psychology, Health, and Medicine, 8, 317-328. Mohamed, M. B., & Sawandi, N. B. 2007. Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) activities in mobile telecommunication industry: case study of Malaysia. In Europ ean Critical Accounting Conference, Scotland, United Kingdom (pp. 1-26). 16 Proceedings of 10th Asia - Pacific Business and Humanities Conference 22 - 23 February 2016, Hotel Istana, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia ISBN: 978-1-925488-00-5 Montano, D. E., Kasprzyk, D., Glanz, K., Rimer, B. K., & Viswanath, K. 2008. Theory of reasoned action, theory of planned behavior, and the integrated behavioral model. Montano, D. E., & Kasprzyk, D. 2002. The theory of reasoned action and the theory of planned behavior. In K. Glanz, B. K. Rimer, & F. M. Lewis (Eds.), Theory, research, and practice in health behavior and health education. San Francisco, CA: Josey Bass. Morris, S. 2000. Defining the nonprofit sector: Some lessons from history. Voluntas: International Journal of Voluntary and Nonprofit Organizations, 11(1), 25-43. Mulla, Z. R., & Krishnan, V. R. 200). Karma Yoga: A conceptualization and validation of the Indian philosophy of work. Journal of Indian Psychology, 24(1), 26-43. Mullen, J. 1997. Performance-based corporate philanthropy: How “giving smart" can further corporate goals. Public Relations Quarterly, 42, 42-48. Murillo, D., & Lozano, J. M. 2006. SMEs and CSR: An approach to CSR in their own words. Journal of Business Ethics, 67(3), 227-240. Nasir, N. E. M., Halim, N. A. A., Sallem, N. R. M., Jasni, N. S., & Aziz, N. F. 2015. Corporate Social Responsibility: An Overview from Malaysia. J. Appl. Environ. Biol. Sci, 4(10S), 82-87. Nejati, M., & Amran, A. 2009. Corporate social responsibility and SMEs: exploratory study on motivations from a Malaysian perspective. Business strategy series, 10(5), 259-265. Park, J. Z., & Smith, C. 2000. ‘To Whom Much Has Been Given...’: Religious Capital and Community Voluntarism Among Churchgoing Protestants. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion, 39(3), 272-286. Pavlou, P. A., & Fygenson, M. 2006. Understanding and predicting electronic commerce adoption: An extension of the theory of planned behavior. MIS quarterly, 115-143. Porter, M. E., & Kramer, M. R. 2006. The link between competitive advantage and corporate social responsibility. Harvard business review, 84(12), 78-92. Potter, K. H. 1964. The naturalistic principle of Karma. Philosophy East and West, 39-49. Putnam, R. 2001. Social capital: Measurement and consequences. Canadian Journal of Policy Research, 2(1), 41-51. Rasche, A., & Kell, G. (Eds.). 2010. The United Nations global compact: Achievements, trends and challenges. Cambridge University Press. Rupp, D. E., Williams, C. A., & Aguilera, R. V. 2011. Increasing corporate social responsibility through stakeholder value internalization (and the catalyzing effect of new governance): An application of organizational justice, self-determination, and 17 Proceedings of 10th Asia - Pacific Business and Humanities Conference 22 - 23 February 2016, Hotel Istana, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia ISBN: 978-1-925488-00-5 social influence theories. Managerial ethics: Managing the psychology of morality, 71-90. Sanchez, C. M. 2000. Motives for corporate philanthropy in El Salvador: Altruism and political legitimacy. Journal of Business Ethics, 27(4), 363-375. Sargeant, A., Ford, J. B., & West, D. C. 2006. Perceptual determinants of nonprofit giving behavior. Journal of Business Research, 59(2), 155-165. Sekaran, U. 2003. Research methods for business . Hoboken. Singh, K. S. D., Islam, M. A., & Ariffin, K. H. K. 2015. Factors Influencing Philanthriphie CSR: A Review. International Business Management, 9(1), 28-34. SMECORP, 2012, SME Master Plan 2012-2020, National SME Development Council, Malaysia. Smith, J. R., & McSweeney, A. 2007. Charitable giving: The effectiveness of a revised theory of planned behaviour model in predicting donating intentions and behaviour. Journal of Community & Applied Social Psychology, 17(5), 363-386. The Star Online. Five generous Malaysians in Forbes Asia list of philanthropists. [Online] available at: http://www.thestar.com.my/News/Nation/2012/07/02/Five-generousMalaysians-in-Forbes-Asia-list-of-philanthropists/ [Accessed 22/1/2015]. Ton, A. Asian Philanthropists Are More Focused on Short-Term Results, Says New Survey. Asian Philanthropy Forum [Online] available at: http://www.asianphilanthropyforum.org/asian-philanthropists-focused-short-termresults-says-new-study/ [Accessed 3/3/2015]. Top10 Malaysia Online. Companies Doing Good: A Step in the Right Direction. [Online] available at: http://top10malaysia.com/home/index.php/top-10-articles/companiesdoing-good [Accessed 16/3/2015]. Udayasankar, K. 2008. Corporate social responsibility and firm size. Journal of Business Ethics, 83(2), 167-175. Valor, C. 2006. Why do managers give? Applying pro-social behaviour theory to understand firm giving. International Review on Public and Non Profit Marketing, 3(1), 17-28. Varadarajan, P. R., & Menon, A. 1988. Cause-related marketing: A coalignment of marketing strategy and corporate philanthropy. The Journal of Marketing, 58-74. Watson, T. 2014, ‘Annual Philanthropy Numbers on the Rise: U.S. Giving Nears PreRecession Levels’, Forbes Online 17 June. Werbel, J. D., & Carter, S. M. 2002. The CEO's influence on corporate foundation giving. Journal of Business Ethics, 40(1), 47-60. 18 Proceedings of 10th Asia - Pacific Business and Humanities Conference 22 - 23 February 2016, Hotel Istana, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia ISBN: 978-1-925488-00-5 Woods, K. 2006. Charity vs. philanthropy. [Online] available at: http://www.acton.org/pub/commentary/2006/07/12/charity-vs-philanthropy. [Accesed 22/2/2015]. Wulfson, M. 2001. The ethics of corporate social responsibility and philanthropic venturesl. Journal of Business Ethics, 29(1-2), 135-145. 19