Proceedings of Annual Tokyo Business Research Conference

advertisement

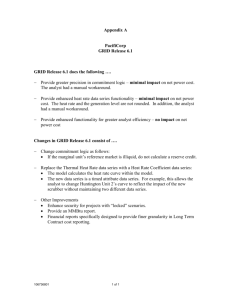

Proceedings of Annual Tokyo Business Research Conference 9 - 10 November 2015, Shinjuku Washington Hotel, Tokyo, Japan, ISBN: 978-1-922069-88-7 Investor Responses to Analyst Reports Kyung Soon Kim*, Jin Woo Park† and Yun Woo Park‡ Using trading data from the Korean equity market, we investigate whether there is any difference amongst individual investors, domestic and foreign institutional investors in trading volume responses to analyst reports. We also examine the determinants of trading volume responses using firm as well as forecast characteristics. Individual investors are the most responsive investor group, being more responsive to analyst reports on small, neglected firms with large inside ownership as well as to analyst reports with optimistic forecasts. Domestic institutional investors are more responsive to reports on neglected firms with high return volatility while foreign institutional investors show least responses. Keywords: Informativeness of Analyst Reports, Trading Volume Response, Institutional Investors, Individual Investors Track: Finance JEL Classification Code: G14; M4 Introduction Individual investors differ in access to information and degree of sophistication from institutional investors, and may show different trading responses to analyst reports than do institutional investors. This may be particularly relevant in a market characterized by a high proportion of trading activities attributable to individual investors. While most of the existing studies investigate the informativeness of analyst reports, these findings have been based on the aggregate measures that implicitly assume market participants as a homogeneous group. Little is known about the difference in the informativeness of analyst reports across investor types. Thus, this study measures the trading volume responses on the release date of the analyst reports by investor types, and analyzes the determinants of the trading volume responses by investor types. More specifically, we divide investors into three classes of investors; namely, individual investors, domestic institutional investors, and foreign institutional investors. We then examine whether the trading responses to analyst reports vary across investor types, and how firm characteristics and characteristics of analyst reports influence the trading activities on the release dates across investor types. * Assistant Professor of Accounting, Division of Business Administration, Chosun University, 309 Pilmun-daero Dong-gu, Gwangju, 501-759 Korea; Tel) +82-62-230-6831, Fax) +82-62-226-9664, E-mail) kskim66@chosun.ac.kr. † Corresponding Author: Professor of Finance, College of Business Administration, Hankuk University of Foreign Studies; 270 Imun-dong Dangdaemun-gu, Seoul 130-791, Korea; Tel) +82-2-2173-3175, Fax) +82-2-2173-2949, Email: jwp@hufs.ac.kr ‡ Professor of Finance, College of Business Administration, Chung-Ang University; 221 Heuseok-dong Dongjak-gu, Seoul 156-756, Korea; Tel)+82-2-820-5793 Fax) +82-2-813-8910, E-mail : yunwpark@cau.ac.kr Proceedings of Annual Tokyo Business Research Conference 9 - 10 November 2015, Shinjuku Washington Hotel, Tokyo, Japan, ISBN: 978-1-922069-88-7 We use the Korean stock market data, which offer critical advantages in testing our hypothesis. First, a study of the trading volume responses to analyst reports by investor types calls for daily trading volumes by investor types.1 This unique data set is fully available for all stocks traded on the Korea Exchange (KRX), enabling us to measure trading volume responses on the release dates of the analyst reports by investor types. Next, there may be a different motivation for information provision in the emerging markets where the trading volume of individual investors is significantly higher than that in the developed markets dominated by institutional investors. Thus, this paper examines the information effect of analyst reports in the Korean market where the relative importance of individual investors is high.2 Also, the Korean stock market is one of the emerging markets in which foreign investors trade actively.3 Given their increasing ownership and significant influence, the trading behavior of foreign investors has received much attention in the stock markets. Thus, it would be interesting to investigate whether foreign investors exhibit different trading response to analyst reports as compared with the response of domestic institutional investors and individual investors. There are competing hypotheses on the role of analysts in the capital market, motivation for information provision by analysts, and the impact of analyst research on stock price. Regulators and market participants generally hold the view that analyst reports on average reduce the information asymmetry that exists between firms and investors and enhances the efficiency of the market. Some studies, such as Lys and Sohn (1990) and Francis and Soffer (1997), document that by and large analyst reports convey value-related information to the market. Furthermore, Hong et al. (2000) and Elgers et al. (2001) report that analyst 1 Many attempts have been made to indirectly measure high-frequency institutional and individual trading volume in the U.S. market. The most common procedure is to partition trades by dollar size, indentifying orders above (below) the cutoff size as institutional (individual), with an intermediate buffer zone of medium-size trades that are not classified (e.g., Hvidkjaer, 2008; Malmendier and Shanthikumar, 2007). However, this method sometimes misclassifies institutional trading as an individual one since institutions have incentives to avoid detection by intermediaries and use order-splitting techniques in order to disguise their trades (Campbell et al., 2009). 2 The trading volume of individual investors is remarkable in comparison to the U.S. market, in which institutions are the dominant investor category. The Korea Exchange (KRX) reports that individual investors dominate trading volumes on the KRX, accounting for 88.19% of total market activity (domestic institutions 5.37%, foreign investors 4.99%) over the January 2001–December 2009 period. On the basis of trading values, individuals' share of total trading remains dominant but at 61.32% of total market activity (domestic institutions 17.27%, foreign investors 18.23%). 3 Foreign ownership has dramatically increased in Korea since 1998 when foreign investors were allowed to purchase stocks of listed corporations freely with the exception of a few state-owned corporations. On the strength of a series of liberalization measures, the Korean stock market has become among the world’s most globalized. Foreign investors own 31% of the capitalization of Korean stock as of the end of 2010. 1 Proceedings of Annual Tokyo Business Research Conference 9 - 10 November 2015, Shinjuku Washington Hotel, Tokyo, Japan, ISBN: 978-1-922069-88-7 activity increases the speed with which public information is impounded in stock price. According to Brennan and Subramanyam (1995), analyst activity reduces the adverse selection cost in stock trading as well as information asymmetry. On the other hand, some studies argue that analyst reports do not provide value relevant information to investors. There are at least three factors that reduce the informativeness of analyst reports. First, Irvine (2000), Lin and McNichols (1998), and Cowen et al. (2005) point out that analysts have the incentive to enhance the profitability of brokerage firms they work for. Next, Bhushan (1989b), Francis et al. (2002), and Frankel and Li (2004) argue that the increase in the timeliness of voluntary financial disclosure replaces the usefulness of the analyst reports. Third, according to Lin and McNichols (1998), Michaely and Womack (1999), Dechow et al. (2000), and O’Brien et al. (2003), conflicts of interest exist because analysts have private objectives leading them to become optimistically biased. In order to test these different views, prior studies analyze the determinants of the informativeness of analyst reports using analyst following as well as earnings forecast accuracy as proxies of informativeness. However, for the analyst following to be a good proxy of informativeness, we have to assume that analyst following automatically increases for firms about which there are vast amounts of information. Also, for earnings forecast accuracy to be a good proxy of informativeness, we have to assume that the more accurate the earnings forecast is, the greater is the impact it has on the stock price. Rather than using proxies, Frankel et al. (2006) utilize the stock price response to analyst reports in order to directly measure the informativeness of analyst reports. Using the U.S. data, they measure the informativeness of analyst reports by the size of the average abnormal return on the publication dates of the analyst reports on an individual firm. Then, they analyze the determinants of the informativeness of analyst reports. As in Frankel et al. (2006), this study investigates the informativeness of analyst reports using the average market response on the release dates of the analyst reports. However, this study differs from the previous studies in the following aspects. First, we measure the trading volume responses to analyst reports by investor types (individuals, domestic institutions, and foreign institutions), then analyze whether there is any difference in the determinants of the trading responses by investor types. Frankel et al. (2006) measure the informativeness of analyst reports by the size of the change in the expectation of the firm value by market participants (the absolute value of average abnormal returns). However, due to differences in the degree of information asymmetry and investment rationality, different 2 Proceedings of Annual Tokyo Business Research Conference 9 - 10 November 2015, Shinjuku Washington Hotel, Tokyo, Japan, ISBN: 978-1-922069-88-7 investor types may perceive the informativeness of the same analyst reports differently. For this reason, we examine whether individual investors, domestic institutional investors, and foreign institutional investors perceive the informativeness of analyst reports differently and exhibit different trading behaviors. Second, we study the trading responses to analyst reports in a market characterized by an active participation of individual investors. According to Marhfor et al. (2010), who compare the effect of analyst coverage on the stock price by countries, the analyst coverage has a positive influence on the stock price in the U.S. and other developed markets, where the relative importance of the domestic institutional investors is high and the disclosure regulation is strict. On the other hand, the analyst coverage has a little effect on the stock price in the emerging markets, where the relative importance of the domestic institutional investors is low and the disclosure regulation is lax. Since the emerging markets present economic environments where individual investors exert a greater influence on the market than in the U.S. and other developed markets, there may be a different motivation for information provision in the emerging markets than in the developed markets. That is, in the developed markets where the trading volume of institutional investors is high, the increase in the trading activity of institutional investors contributes the most to the profits of brokerage firms, and thus analysts are motivated to offer differentiated reports that satisfy the informational needs of institutional investors. In contrast, in the emerging markets where the trading volume of individual investors is high, analysts may concentrate information provision on firms as to the low cost to produce information while leading to greater trading activities of individual investors. Therefore, by examining the information effect of analyst reports in the Korean market, our study sheds light on the effect of information environment on the usefulness of analyst reports in markets where the relative importance of individual investors is high. 2. Literature Review Prior research explains the role of analysts from two perspectives. First, analysts play the role of private information providers who acquire private information on the fundamentals of the firm and convey the value-related forecasts to the market. Second, analysts play the role of an information intermediary who simply transmits disclosed information to market participants on behalf of the firm's management rather than competing with the firm for firm-related information sources (Lang and Lundholm, 1996). Since the 3 Proceedings of Annual Tokyo Business Research Conference 9 - 10 November 2015, Shinjuku Washington Hotel, Tokyo, Japan, ISBN: 978-1-922069-88-7 informativeness of analyst reports (AI) may depend on the role that analysts play in the capital markets, some studies analyze the determinants of AI in order to infer the role of analysts in the capital markets. Studies on the determinants of AI can be divided into those that take the perspectives of information provider and those that take the perspectives of information demander. Studies on the determinants of AI that take the perspectives of information provider use the analyst following as a proxy for AI (Bhushan, 1989; O'Brian and Bhushan, 1990; Lang and Lundholm, 1996; McNichals and O'Brian, 1997; Alford and Berger, 1999). Bhushan (1989) proposes that, as analyst following increases in information demand and decreases in information provision cost, the equilibrium number of analysts is obtained at the intersection between the demand curve and supply curve of analysts’ service. Since analysts research firms about which there exists valuable information, Bhushan (1989) posits that AI increases in analysts following. In addition, he examines firm characteristics that influence the demand and supply of analysts’ service, and then investigate their marginal effects. He finds that informativeness of analyst reports is an increasing function of informational demands of market participants and a decreasing function of informational production costs faced by analysts. Hence, they infer the role of analysts in the market by investigating whether firm characteristics, which can influence both the informational demands and the information production costs, have a positive or negative marginal effect on the proxy of informativeness. On the other hand, Frankel et al. (2006) analyze the determinants of the AI using the market response by information demanders instead of using a proxy. They interpret a larger market response (the absolute value of the abnormal return) on the release dates of analyst reports as analyst reports being more informative. Then they analyze various factors that have an influence on the market responses to the analyst reports. They report that the market responses to analyst reports increase as demands for analysts' service increase and decrease as costs of information provision increases. Similar to studies based on analyst following, the findings of Frankel et al. (2006) suggest that the provision of private information is an important impetus for the analyst activity. Studies that investigate the informativeness of analyst reports in the U.S. markets conclude that by and large analyst reports are informative and that the informativeness of analyst reports stems from the fact that analyst activity is motivated by the provision of private information. However, Marhfor et al. (2010) report that the effect of analyst coverage on stock price informativeness depends on the environments of the individual countries. They argue that in the developed markets where the weight of domestic institutional 4 Proceedings of Annual Tokyo Business Research Conference 9 - 10 November 2015, Shinjuku Washington Hotel, Tokyo, Japan, ISBN: 978-1-922069-88-7 investors is high and disclosure regulation is strict, analysts have strong motivation to provide private information and as a result, analyst following has a positive influence on the stock price. On the contrast, in the emerging markets where the weight of domestic institutional investors is high and disclosure regulation is strict, analysts act merely as information transmitters and as a result, analyst following has little influence on the stock price. While analysts have an incentive to provide information to investors, they also have an incentive to provide information as a marketing tool for brokerage firms (Irvine, 2000; Lin and McNichols 1998; Cowen et. al 2005). Particularly in the emerging markets, where the relative importance of trading activities by individual investors is high, analysts may have a stronger incentive to provide analyst reports with a view to increase the trading activity at low information provision costs than in the developed markets. If a marketing incentive is greater than the incentive to provide private information, analyst following may not be an appropriate proxy for private information production. For this reason, we use the market response rather than analyst following in order to see whether analyst reports provide value-related information. Studies that examine trading behaviors by investor types show that because of differences in investor rationality, investment strategy, and investment horizon investors have different preferences for firm characteristics (Eakins et al., 1998; Gompers and Metrick, 1999; Chen and Lakonishok, 1999; Kang and Stulz, 1997; Brennan and Cao, 1997). These investor idiosyncrasies may give rise to different responses to analyst reports. This may be particularly relevant in the context of the Korean stock market, which is characterized by a high proportion of trading activities attributable to individual investors as well as foreign investors. The diversity of market participants may influence motivations of analysts in information provision. Therefore, we divide the market participants into individual investors, domestic institutional investors, and foreign institutional investors. Further, we measure the responses to analyst reports and examine the factors that influence market responses by investor types. 3. Explanations on Variables We measure trading volume responses on the release dates of analyst reports and analyze factors that influence trading volume responses by investor types. In section 3.1, we show how we measure the informativeness of analyst reports for all market participants as well as different investor types. In section 3.2, 5 Proceedings of Annual Tokyo Business Research Conference 9 - 10 November 2015, Shinjuku Washington Hotel, Tokyo, Japan, ISBN: 978-1-922069-88-7 we provide explanations on factors that may influence the degree of informativeness of analyst reports for different investor types, and further, we describe the methods used to measure them. Bhushan (1989b) argues that the number of analysts depends on the supply and demand of analysts’ service, and the informativeness of analyst reports is an increasing function of the number of analysts. On the basis of this argument, he examines the determinants of the informativeness of analyst reports using analyst following as a proxy for the informativeness of analyst reports. On the other hand, Frankel et al. (2006) measure the informativeness of analyst reports using the average stock price response rather than using a proxy. The focus of this paper is to examine whether individuals perceive the informativeness of the analyst reports differently than institutional investors and to look into the reasons for this difference if any. Therefore, there is a similarity between this study and the study by Frankel et al. (2006) in that both studies use the market response to measure the informativeness of analyst reports by using the average market response on the release dates of analyst reports. However, unlike Frankel et al. (2006), who measure the informativeness of analyst reports using the change in the expectation of all market participants, we divide market participants into individual investors, domestic institutional investors, and foreign institutional investors. We then measure the trading volume responses as well as their determinants by investor types. We measure the market responses to analyst reports by all market participants and then by investor types. Equations (1) and (2) show market responses of all market participants using returns and trading volume, respectively. Equations (3)-(5) measure responses to analyst reports by individual investors, institutional investors, and foreign investors, respectively. 1) Market responses to analysts reports 1 NREVS i Rijt RSIZE jt t 1 NREVSi 1 AI i 1 N N R RSIZE j ,t t 1 ijt N (1) 1 NREVS i TVit t 1 NREVSi AITVi 1 N TVit t 1 N (2) 6 Proceedings of Annual Tokyo Business Research Conference 9 - 10 November 2015, Shinjuku Washington Hotel, Tokyo, Japan, ISBN: 978-1-922069-88-7 2) Trading volume responses of each investor type AITV _ INST NREVS i t 1 N i N NREVSi N MTV _ INSTit t 1 NREVS i AITV _ INDIi MTV _ INSTit t 1 N MTV _ INDIit MTV _ INDIit t 1 AITV _ FORE NREVS i i t 1 N MTV _ FOREit MTV _ FOREit t 1 (3) (4) NREVSi N (5) NREVSi First, AI in equation (1) is the measure of the informativeness of analyst reports based on Frankel et al. (2006). AIi is the ratio of the average absolute size-adjusted excess return on the release dates of analyst reports on firm i to the annual cumulative absolute size-adjusted excess return on firm i. Rijt is the daily return of firm i in industry j on day t. RSIZEjt is the daily return of portfolio j on day t where five equally weighted portfolios are formed on the basis of year-end market capitalization. NREVSi is the number of release dates of analyst reports on firm i in a given year, and N is the total number of trading days in year t. If the analyst reports are not informative, the average release date excess return would be similar to the average excess return over the year. If are the same, equation (1) reduces to 1 N 1 NREVS t 1 Rijt RSIZE jt and t 1 i Rijt RSIZE jt N NREVSi 1 . Furthermore, if we assume 250 trading days per year, then AI N would be 0.004. Therefore, the report would not be informative if AI is not statistically significantly different from 0.004. On the other hand, the report would be informative if AI is statistically significantly greater than 0.004. 7 Proceedings of Annual Tokyo Business Research Conference 9 - 10 November 2015, Shinjuku Washington Hotel, Tokyo, Japan, ISBN: 978-1-922069-88-7 AITV in equation (2) is an alternative measure of the informativeness of analyst reports, which is the trading volume response on the release dates of analyst reports. AITVi is the ratio of the average trading volume on the release dates of analyst reports on firm i to the annual average trading volume. TVit is the daily total trading volume of firm i on day t. If analyst reports have no informativeness, the average trading volumes on the release dates will not be any different than the average trading volumes over the year; thus, AITVi in equation (2) will reduce to 1. The same holds for AITV_INST, AITV_INDI, and AITV_FORE. 4. Empirical Results 4.1 Sample selection We sample firms with a December fiscal year-end for which there is one or more analyst reports for the 2005-2009 period. Of these, we exclude financial firms as well as firms with negative book equity. We also exclude the first year after an IPO for firms which underwent the IPO during the study period. In addition, we exclude firms for which we do not find either the accounting or the market data from FnGuide Data Guide Pro. As a result, we arrive at a sample of 1,225 firm-years. In particular, we hand-collect the release dates as well as the number of analyst reports from the Research Reports of FnGuide. We obtain the accounting information, stock price, and trading volume of sample firms from FnGuide Data Guide Pro as well as from the Financial Supervisory Services DART (electronic disclosure system), which we use to measure the informativeness of the analyst reports. Table 1 shows the number of reports that brokerage firms have published on sample firms, as well as the number of days analyst reports have been published by year. NREPORTS is the number of analyst reports that brokerage firms have published on firm i in year t; NREVS is the number of days when analyst reports are published on firm i in year t. Table 1 shows that the number of firms analysts cover (N) increases from 231 to 287, and the average number of reports per firm (NREPORTS) increases from 36.31 to 53.42 during the sample period. On the other hand, the median number of reports per firm shows little change. While the average number of coverage days per firm (NREVS) rises from 23.33 to 30.32, the median slightly changes. 8 Proceedings of Annual Tokyo Business Research Conference 9 - 10 November 2015, Shinjuku Washington Hotel, Tokyo, Japan, ISBN: 978-1-922069-88-7 We find that the analyst following is heavily concentrated on a few large and well-known firms while smaller firms are essentially neglected. For example, in 2009 the number of analyst reports on the firm with the greatest analyst following is 345 while the number of analyst reports of the median firm is 16 showing the asymmetric coverage. [Insert Table 1 about here] 4.2 Tests of informativeness of analyst reports on the release dates Table 2 shows the sample means as well as the corresponding t-statistics of various measures of informativeness of analyst reports. Panel A shows the measures of trading volume responses of all investors to analyst reports organized by year. AI is greater than 0.004 every year and the difference is statistically significant, showing that investors perceive analyst reports as informative. AITV is greater than 1 every year and the difference is statistically significant, showing that analyst reports change the expectations of investors leading to changes in the trading volume. [Insert Table 2 about here] Panel B shows the trading volume response of each investor type to analyst reports. All investor types show trading response measures greater than 1, and the differences are statistically significant. However, there are differences in the trading volume responses to analyst reports from one investor type to another. The volume responses of individual investors measured by AITV_INDI are the largest, whereas those by foreign institutional investors are the least. 4.3 Effect of the trading behaviors of each investor type on the overall market responses In order to find out which investor group has the most influence on the overall market responses, we analyze the effect of the trading volume responses of each investor type on the overall market responses. Table 3 shows the regression estimates. [Insert Table 3 about here] 9 Proceedings of Annual Tokyo Business Research Conference 9 - 10 November 2015, Shinjuku Washington Hotel, Tokyo, Japan, ISBN: 978-1-922069-88-7 Regression estimates show that the release date abnormal return (AI) is most sensitive to the trading activities of individual investors, whereas the effect of the trading activities of institutional investors, both domestic and foreign, is not statistically significant. Regression estimates show that the trading volumes of individual investors have the greatest effect on the trading volumes of the market, whereas the trading volumes of both domestic and foreign traders have a limited effect on the trading volumes of the overall market. This result suggests that individual investors perceive analyst reports to be the most informative. This may be due to the fact that, in a market characterized by a high proportion of the direct investment by individual investors, analysts have an incentive to provide research reports that cater to individual investors. 4.4 Determinants of trading volume responses to analyst reports for each investor type Results reported above show that individual investors are the most responsive while foreign institutional investors are the least responsive. Given that responses to analyst reports are different across investor types, there may be differences in the determinants of the trading responses to analyst reports. Therefore, we examine the determinants of the trading response to analyst reports for each investor type and investigate the motivations for analysts to provide information and compare the differences amongst investor groups. Table 4 shows the results of the 2-SLS regression analysis, which expresses the relationship between the trading volume responses and their determinants for each investor type. The dependent variables are (1) AITV, (2) AITV_INST, (3) AITV_INDI, and (4) AITV_FORE, respectively. We conduct the FamaMacBeth regression, where we subdivide the sample by year to reduce heteroskedasticity. The results in Table 4 exhibit the time-series means of the estimated coefficients of the Fama-MacBeth regression. We test the statistical significance of regression coefficients using the standard error of the yearly t-statistics, as in Barth (2001) and Frankel et al. (2006).4 [Insert Table 4 about here] 4 We also conduct the fixed effect panel regression, and obtain almost identical results as in Fama-MacBeth regression. Thus the results of the fixed effect regression are omitted in this paper. 10 Proceedings of Annual Tokyo Business Research Conference 9 - 10 November 2015, Shinjuku Washington Hotel, Tokyo, Japan, ISBN: 978-1-922069-88-7 We find that trading volume responses of all investors on the release dates (AITV) have a negative relationship with the number of analyst reports (LOG_NREPORTS) as well as the correlation with the market (MMRSQ). This may be due to the fact that analysts face a high cost of providing information on firms with a large analyst following. As a consequence, they fail to deliver informative reports, and the market concludes that the analyst reports are low in informativeness. Advertising expenses as well as debt ratio have a negative relationship with the trading volume responses. This may be due to the fact that investors are already aware of firms that incur a large advertising expense and have a low regard for information in the analyst reports on high debt firms. Share ownership of insiders (INSIDER) shows a positive influence on the trading volume responses. This result is consistent with the interpretation that investors show a great responsiveness to information on firms that investors perceive to be opaque. Good news (GNEWS) shows a positive influence on the trading volume responses. This suggests that the overall investors show a positive response to optimistic reports. Next, we turn to models of each investor type that examine factors that influence the trading volume responses. Determinants of trading volume responses of individual investors are almost identical to those of the overall investors. This result suggests that the perceived informativeness of analyst reports is mainly attributable to individual investors, which is consistent with the results in Table 3. In comparison, trading volume responses of individual investors on the release dates of analyst reports (AITV_INDI) show a negative relationship with the analyst following (LOG_NREPORTS), the correlation with the market (MMRASQ), the advertising expenses (ADVER), and the debt ratio (DEBT), while showing a positive relationship with insiders’ share ownership (INSIDER) and good news dummy (GNEWS). Trading volume responses of individual investors increase with the number of firms in the industry (IND_R). This result may be due to the fact that individual investors fail to recognize the transmission of information within the industry so that they respond to information on firms with large intraindustry information transmission. As for domestic institutional investors trading volume responses (AITV_INST) increase with the return volatility (FIT_VAR), suggesting that domestic institutional investors are more responsive to reports on firms with high volatility, that is, high information asymmetry. Second, we find that trading volume responses of domestic institutional investors are lower for a firm with a larger analyst following (LOG_NREPORTS), suggesting that domestic institutional investors are more responsive to reports on 11 Proceedings of Annual Tokyo Business Research Conference 9 - 10 November 2015, Shinjuku Washington Hotel, Tokyo, Japan, ISBN: 978-1-922069-88-7 neglected firms. The latter result is also consistent with the interpretation domestic institutional investors have a lower regard for information in the analyst reports on a large firm as well as a firm with a large analyst following. Finally, we note that overall their responses to proposed determinants are more limited than those of individual investors. This may be either due to the fact that domestic institutional investors are less responsive to proposed factors than individual investors or the fact that the tests are not powerful enough to capture the effects of the proposed determinants. Finally, as for foreign institutional investors we find that the positive news has a positive influence on the trading volume responses of foreign institutional investors, while advertising expenses have a negative influence, and the effects of the other factors are not statistically significant. Therefore, we conclude that foreign institutional investors show the least response to analyst reports overall. This may be either due to the fact that foreign institutional investors do not find the analyst reports informative or the fact that the tests are not powerful enough to capture the effects of the proposed determinants. In summary, the relationships between the trading volume responses and their determinants across investor types are as follows. First, market responses to analyst reports are driven primarily by individual investors. Second, individual investors show a large response to small firms; they show a positive response to optimistic forecasts; they fail to take advantage of intra-industry information spill-over effects. Third, domestic institutional investors respond to neglected firms, which present large information asymmetry, and firms with large return volatility, suggesting that they may be informed traders. Fourth, domestic institutional investors as well as individual investors respond less to firms with more analyst activity suggesting that the analysts’ role is information transmitter rather than the information provider in the emerging market dominated by individual investors. 6. Summary and Conclusions Due to differences in access to information and investor rationality, different investor types may perceive the informativeness of analyst reports from the same brokerage firm differently. However, there are few studies that investigate whether the trading responses to analyst reports vary across investor types and how firm characteristics and characteristics of analyst reports influence the trading activities on the release dates across investor types. Taking advantage of the trading volume data for the three main investor types in 12 Proceedings of Annual Tokyo Business Research Conference 9 - 10 November 2015, Shinjuku Washington Hotel, Tokyo, Japan, ISBN: 978-1-922069-88-7 the Korean stock market, we study the trading volume responses for each investor type and make comparisons across investor types. We use 1,225 firms, for which there has been at least one analyst reports for the 2005-2009 period. The main findings are as follows. First, the release date abnormal returns as well as the trading volume responses are positive and statistically significant, indicating that investors tend to find the information in the analyst reports informative. Second, the regression results of the models that study the responses of the overall market as well as the trading responses of each investor type show that trading behaviors of the individual investors mostly influence the overall market response. To foreigner institutional investors the analyst reports do not appear to be informative. Of the firm characteristics, the return volatility has a positive influence on the trading volume responses of domestic institutional investors, while the firm size and the analyst following have a negative influence on the trading volume responses of domestic institutional investors. Trading volume responses of individual investors show a negative relationship with the analyst following, correlation with the market, advertising expenses, and debt ratio, while having a positive relationship with the insiders’ share ownership, the number of firms in the industry, and the optimistic reports. On the other hand, the trading volume responses of foreign institutional investors show no discernible relationship with most of the firm characteristics considered. Our findings suggest the following. In markets where individual investors are responsible for a large share of trading volume, individual investors are the most responsive to analyst reports of all investor types. In particular, individual investors show a large response to reports on small firms as well as to optimistic reports. Domestic institutional investors respond to information on neglected firms characterized by large information asymmetry. Foreign institutional investors show limited response to analyst reports, suggesting that they find the information least informative. 13 Proceedings of Annual Tokyo Business Research Conference 9 - 10 November 2015, Shinjuku Washington Hotel, Tokyo, Japan, ISBN: 978-1-922069-88-7 REFERENCE Alford, A., Berger, P., 1999. A simultaneous equations analysis of forecast accuracy, analyst following, and trading volume. Journal of Accounting, Auditing, and Finance 14, 219–240. Barth, M., Kasznik, R., Mcnichols, M., 2001. Analyst coverage and intangible assets, Journal of Accounting Research 39, 1-34. Beaver, W., 1968. The information content of annual earnings announcements. Journal of Accounting Research Supplement 6, 67–92. Bhushan, R., 1989a. Collection of information about publicly traded firms: Theory and evidence. Journal of Accounting and Economics 11, 183-206. Bhushan, R., 1989b. Firm characteristics and analyst following. Journal of Accounting and Economics 11, 255–274. Brennan, M., Cao, H., 1997. International portfolio investment flows. Journal of Finance 52, 1851–1880. Brennan, M.,Subramanyam, A., 1995. Investment analysis and price formation in securities markets. Journal of Financial Economics 38, 361-381. Campbell, J. Y., Ramadorai, T., Schwartz, A., 2009. Caught on tape: Institutional trading, stock returns, and earnings announcements. Journal of Financial Economics 92, 66–91. Chan, L., Chen, H., Lakonishok, J., 2002. On mutual fund investment styles. Review of Financial Studies 15, 1407-1437. Cowen, A., Groysberg, B., Healy, P., 2006. Which types of analyst firms are more optimistic? Journal of Accounting and Economics 41, 119-146. Das, S., Levine, C., Sivaramakrishnan, K., 1998. Earnings predictability and bias in analyst's earning forecasts. The Accounting Review 73, 277-294. Dechow, P., Hutton, A., Sloan, R., 2000. The relation between analysts’ forecasts of long-term earnings growth and stock price performance following equity offerings. Contemporary Accounting Research 17, 1–32. Durnev, A., Morck, R., Yeung, B., Zarowin, P., 2003. Does greater firm-specific return variation mean more or less informed stock pricing? Journal of Accounting Research 41, 797-836. Eakins, S., Stansell, S., Wertheim, P., 1998. Institutional portfolio composition: An examination of the prudent investment hypothesis. The Quarterly Review of Economics and Finance38, 93-109. Elgers, P., Lo, M., Pfeiffer, R., 2001. Delayed security price adjustments to financial analysts’ forecasts of annual earnings. The Accounting Review 76, 613-632. Foster, G., 1981. Intra-industry information transfers associated with earnings releases. Journal of Accounting and Economics 3, 201–232. Francis, J., Soffer, L., 1997. The relative informativeness of analyst’ stock recommendations and earnings forecast revisions. Journal of Accounting Research 35, 193-211. Francis, J., Schipper, K., Vincent, L., 2002. Earnings announcements and competing information. Journal of Accounting and Economics 33, 313–342. 14 Proceedings of Annual Tokyo Business Research Conference 9 - 10 November 2015, Shinjuku Washington Hotel, Tokyo, Japan, ISBN: 978-1-922069-88-7 Frankel, R., Li, X., 2004. Characteristics of a firm’s information environment and the information asymmetry between insiders and outsiders. Journal of Accounting and Economics 37, 229–259. Frankel, R., Kothari S., Weber J., 2006. Determinants of informativeness of analyst research. Journal of Accounting and Economics 41, 29-54. Gompers, P., Metrick.A., 1999. Domestic institutional investors and equity prices. Quarterly Journal of Economics 116, 229-259. Grullon, G., Kanatas, G., and Weston.J., 2004. Advertising, breadth of ownership and liquidity. Review of Financial Studies 17, 439-461. Harris, M., Raviv, A., 1993. Differences of opinion make a horse race. Review of Financial Studies 6, 473506. Hvidkjaer, S., 2008. Small trades and the cross-section of stock returns. Review of Financial Studies. 21, 1123-1151. Hessel, C., Norman, M., 1992. Financial characteristics of neglected and institutionally held stocks. Journal of Accounting Auditing and Finance 7, 313-334. Hong, H., Lim, T., Stein, J., 2000. Bad news travels slowly: Size, analyst coverage and the profitability of momentum strategies. Journal of Finance 55, 265–295. Irvine, P., 2000. Do analysts generate trades for their firms? Evidence from the Toronto Stock Exchange. Journal of Accounting and Economics 30, 209–226. Kandel, E., Pearson, N., 1995. Differential interpretation of public signals and trade in speculative markets. Journal of Political Economics 103, 831-853. Kang, J., Stulz, R., 1997. Why is there a home bias? An analysis of foreign portfolio equity ownership in Japan. Journal of Financial Economics 46, 3-28. Kim, O., Verrecchia, R., 1991a. Trading volume and price reaction to public announcement. Journal of Accounting Research 29, 302-321 Kim, O., Verrecchia, R., 1991b. Market reaction to anticipated announcement. Journal of Financial Economics 30. 273-309 Kim, O., Verrecchia, R., 1997. Pre-announcement and even-period private information. Journal of Accounting and Economics 24, 395-419 Lang, M., Lundholm, R., 1996. Corporate disclosure policy and analyst behavior. The Accounting Review 71, 467–92. Lin, H., McNichols, M., 1998. Underwriting relationships, analysts’ earnings forecasts and investment recommendations. Journal of Accounting and Economics 25, 101–127. Lys, T., Sohn, S., 1990. The association between revision of financial analyst’s earnings forecasts and security price changes, Journal of Accounting and Economics 13, 341-363. Malmendier, U., Shanthikumar, D., 2007. Are small investors naïve about incentives? Journal of Financial Economics 85, 457-489. Marhfor, A., M'Zali, B., Charest, G., 2010. Stock price informativeness and analyst coverage, Working Paper, University of Quebec at Montreal. Merton, R., 1987. A simple model of capital market equilibrium with incomplete information. Journal of Finance 42, 483-510. 15 Proceedings of Annual Tokyo Business Research Conference 9 - 10 November 2015, Shinjuku Washington Hotel, Tokyo, Japan, ISBN: 978-1-922069-88-7 McNichols, M., O'Brien, P., 1997. Self-selection and analysts coverage. Journal of Accounting Research 35, 167-199. Michaely, R., Womack, K., 1999. Conflict of interest and the credibility of underwriter analyst recommendations. Review of Financial Studies 12, 573– 608. O’Brien, P., Bhushan, R., 1990. Analyst following and institutional ownership. Journal of Accounting Research 28, 55–76. O’Brien, P., McNichols. M., Lin. H., 2005. Analyst impartiality and investment banking relationships. Journal of Accounting Research 43, 623–650. Piotroski, J., Roulstone, D., 2004. The influence of analysts, institutional investors, and insiders on the incorporation of market, industry, and firm-specific information into stock prices. Accounting Review 79, 1119-1151. Verrecchia, R.,1982. Information acquisition in a noisy rational expectation economy. Econometrica 50, 1415-1430. 16 Proceedings of Annual Tokyo Business Research Conference 9 - 10 November 2015, Shinjuku Washington Hotel, Tokyo, Japan, ISBN: 978-1-922069-88-7 Table 1. Analyst activity N is the number of firms covered by analyst reports. NREPORTS is the number of reports that brokerage analysts have published for firm i in year t. NREVS is the number of days when brokerage analysts have published reports. We collect the data from FnGuide Research Report by firm and by year. We count as one the firm that publishes more than one report on a given firm on a given day. Variables NREPORTS NREVS YEAR 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 Total 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 Total N 231 229 242 236 287 1225 231 229 242 236 287 1225 Mean 36.31 36.28 40.27 50.69 53.42 43.87 23.33 22.72 25.16 29.67 30.32 26.44 Std.dev 45.05 45.60 52.05 63.74 71.47 57.71 23.26 22.72 26.29 30.56 33.42 28.01 Min 1.00 1.00 1.00 1.00 1.00 1.00 1.00 1.00 1.00 1.00 1.00 1.00 17 Q1 4.00 5.00 5.00 5.25 5.00 5.00 4.00 5.00 5.00 5.00 5.00 5.00 Median 16.00 14.00 17.00 21.00 16.00 17.00 15.00 12.00 15.00 17.00 14.00 15.00 Q3 49.00 51.50 59.25 75.25 78.00 61.00 36.00 35.00 37.00 44.75 48.00 41.00 Max 190.00 207.00 313.00 337.00 345.00 345.00 94.00 96.00 144.00 156.00 158.00 158.00 Proceedings of Annual Tokyo Business Research Conference 9 - 10 November 2015, Shinjuku Washington Hotel, Tokyo, Japan, ISBN: 978-1922069-88-7 Table 2. Market responses to analyst reports on the release dates This table shows the sample means as well as the corresponding t statistics of various measures of the market responses to analyst reports. Panel A shows abnormal returns (AI) and trading volume responses (AITV) by year. Panel B shows AITV_INST, AITV_INDI, and AITV_FORE, which are trading volume responses of each investor type to analyst reports. * and ** are 5% and 1% significance levels, respectively. Panel A: Market responses AIa) period sample AITVb) mean t-value ** period sample mean ** t-value total 1225 0.0052 18.20 total 1207 1.4757 2005 238 0.0056** 8.65 2005 231 1.6791** 9.49 237 ** 229 1.5777 ** 8.45 1.3980 ** 8.95 1.2554 ** 5.46 1.4698 ** 8.96 2006 2007 2008 2009 249 244 299 0.0054 8.79 ** 0.0054 2006 9.94 ** 0.0047 2007 5.65 ** 0.0051 2008 7.85 2009 234 229 284 18.31 PanalB: Trading volume responses of each investor type AITV_INSTb) AITV_INDIb) AITV_FOREb) period sample mean t-value period sample mean t-value period sample mean t-value total 1205 1.4494** 14.37 total 1225 1.5161** 18.71 total 1198 1.2814** 9.80 2005 229 1.5739** 6.87 2005 231 1.7247** 9.75 2005 222 1.4878** 5.50 2006 223 1.6069** 6.19 2006 229 1.6358** 8.78 2006 221 1.2792** 3.80 2007 240 1.3420** 5.61 2007 242 1.4541** 9.00 2007 239 1.2404** 4.41 2008 235 1.2863** 4.46 2008 236 1.3068** 6.27 2008 231 1.1791** 3.18 2009 278 1.4513** 6.89 2009 287 1.4770** 8.36 2009 285 1.2394** 5.04 a) tests whether AI is different from 0.004. b) tests whether AITV_INST, AITV_INDI, and AITV_FORE are different from 1. 18 Proceedings of Annual Tokyo Business Research Conference 9 - 10 November 2015, Shinjuku Washington Hotel, Tokyo, Japan, ISBN: 978-1922069-88-7 Table 3. Effect of trading behaviors of different investor types on the market response This table shows the regression results that represent the effect of the trading behaviors of different investor types on the market response. Dependent variables (AI and AITV) are measures of the market responses. Independent variables are trading volume responses of different investor types; AITV_INST, AITV_INDI, AITV_FORE.. Control variables are SIZE, YEAR, and ID. *, **, *** are 10%, 5%, 1% significance levels, respectively. Variable CONSTANT AITV_INST AITV_INDI AITV_FORE SIZE (1) AI Coefficient (t-stat) 0.0064*** (2) AITV Coefficient (t-stat) 0.0906** (11.426) (1.688) 0.0001 0.1078*** (1.430) (20.090) 0.0009*** 0.7746** (12.917) (116.735) 0.0001 0.0753*** (1.498) (14.593) -0.0005 *** -0.0062** (-5.151) (-0.721) ΣYEAR Included Included ΣID Included Included 1179 1179 Adj.R 0.279 0.964 F-stat 58.019 4001.917 N 2 19 Proceedings of Annual Tokyo Business Research Conference 9 - 10 November 2015, Shinjuku Washington Hotel, Tokyo, Japan, ISBN: 978-1922069-88-7 Table 4. Effect of firm characteristics on the trading volume responses of each investor type to analyst reports This table shows the results of cross-sectional two-stage least-squares regression models that represent the effect of firm characteristics on the trading responses to analyst reports. We show the time-series means of coefficients, z-statistics for the averages of the coefficients, average adjusted R2, and average number of samples. We indicate the statistical significance of time-series means of coefficients using the standard error of the yearly t-statistics. *, **, *** are 10%, 5%, 1% significance levels, respectively. Variable CONSTANT FIT_VAR FIT_VOL SIZE LOG_NREPORTS INSIDER MB ACCRSQ MMRSQ IND_R GNEWS ADVER TOA DEBT N adj.R2 F-stat (1)AITV Mean Coefficient ( z-stat ) 2.3635*** (3.644) -0.2534 (-0.331) 0.0043 (0.082) -0.0999 (-0.814) -0.2626*** (-3.525) 0.4365 ** (1.992) -0.0070 (0.033) -0.0174 (-0.913) -0.6774*** (-3.420) 0.6530 (1.401) 0.1942*** (3.242) -3.0900*** (-7.212) 0.3308 (0.528) -0.2430** (-2.315) 193.0 0.145 3.650 (2)AITV_INST Mean Coefficient ( z-stat ) 1.8947*** (5.441) 0.7143* (1.809) 0.0199 (0.700) -0.1143* (-1.713) -0.2782*** (-2.754) 0.2672 (0.867) -0.0300 (-0.102) -0.0320 (-0.547) -0.0368 (0.049) 0.1634 (0.852) 0.1556 (1.624) -1.4154 (-0.684) 0.3635 (1.218) -0.3294* (-1.731) 192.2 0.083 2.467 20 (3)AITV_INDI Mean Coefficient ( z-stat ) 2.6461*** (3.537) -0.6203 (-0.758) -0.0027 (-0.499) -0.0849 (-0.673) -0.3080*** (-4.844) 0.4419** (2.092) -0.0047 (0.097) -0.0177 (-0.992) -0.9162*** (-3.548) 0.7507* (1.814) 0.2046*** (3.275) -3.2064*** (-4.770) 0.3370 (0.551) -0.3623*** (-4.402) 194.2 0.157 3.872 (4)AITV_FORE Mean Coefficient ( z-stat ) 1.0272** (2.188) -0.2118 (0.237) 0.0127 (0.760) 0.0369 (0.423) -0.0977 (-0.664) 0.3046 (1.047) -0.0292 (-0.041) -0.0017 (-0.698) -0.6621 (-1.213) 0.3923 (0.950) 0.0989* (1.719) -3.0804** (-2.539) 0.2965 (0.296) -0.0374 (-0.415) 191.6 0.035 1.606