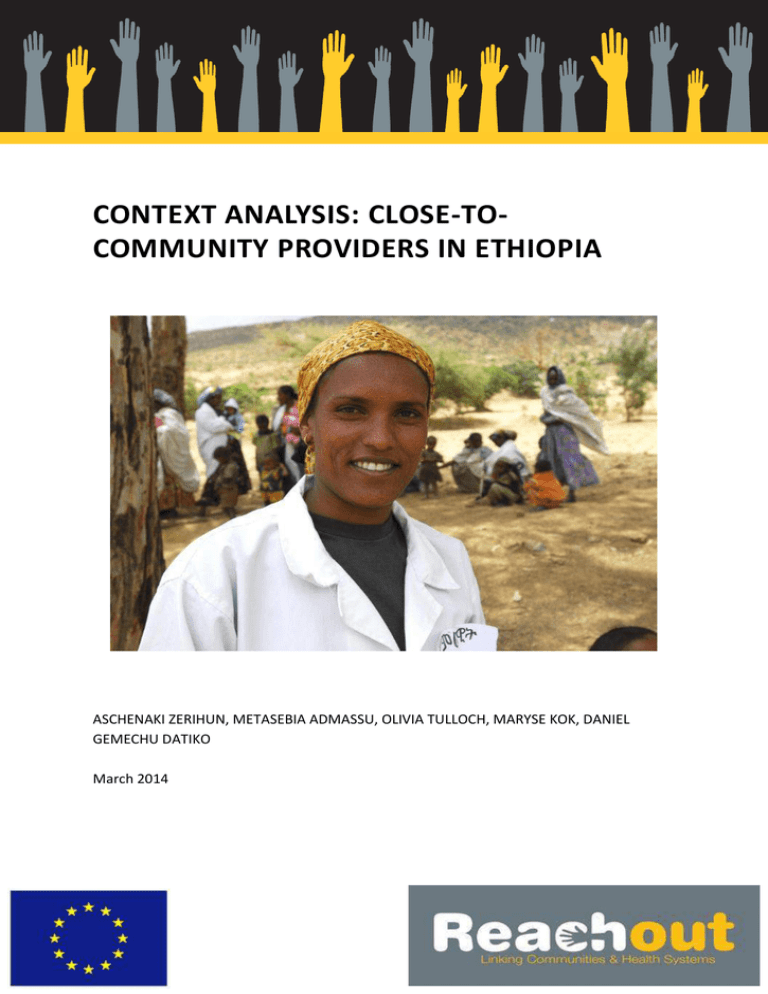

CONTEXT ANALYSIS: CLOSE-TO- COMMUNITY PROVIDERS IN ETHIOPIA

advertisement