Proceedings of World Business Research Conference

advertisement

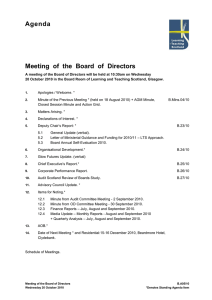

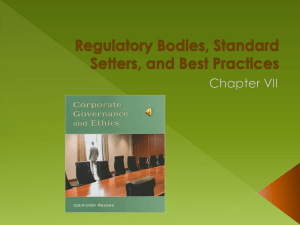

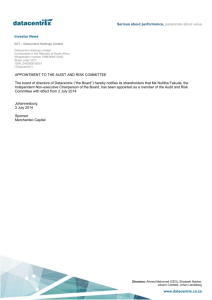

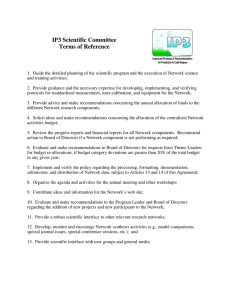

Proceedings of World Business Research Conference 11 - 13 June 2015, Hotel Novotel Xin Qiao, Beijing, China, ISBN: 978-1-922069-78-8 Women Leaders in Banking and Bank Risk Bing Yu*, Mary Jane Lenard, E. Anne York and Shengxiong Wu Our paper examines gender diversity among corporate leadership positions in the banking industry and the relation to bank risk as measured by the variability of stock market return. We examine a sample of companies in the financial industry pulled from the RiskMetrics database, which contains information on executive officers and corporate boards of directors. Our study covers the years from 2003 to 2011, and our findings indicate that more gender diversity on the audit committee and corporate governance committee impacts firm risk by contributing to lower variability of stock market return. The presence of women executives increased bank risk in the early years of our study, but decreased bank risk during the time of the financial crisis. Our research design and findings assist in providing additional evidence about the role of women in corporate leadership positions in the banking industry and the association with corporate performance. Keywords: Risk performance Management, Corporate governance, Gender diversity, Corporate JEL Classification: G32 1 Introduction Research on women leaders is a study in contrasts. On the one hand, shareholders want managers who take risks in order to maximize the value of their equity (Sun and Liu 2014). On the other hand, female CFOs are shown to be more risk-averse than male CFOs (Francis et al. 2013). Studies have also shown that firms with female CFOs adopt more conservative accounting policies (Francis et al. 2014) and are less likely to manipulate earnings (Chava and Purnanandam 2010). In addition, committees of all publicly-traded companies are required to follow strict regulations as a result of the Sarbanes-Oxley (SOX) act of 2002. The (SOX) legislation includes specific requirements for corporate governance, such as the independence of board members and financial expertise on the audit committee (SOX, 2002). As a result, high quality boards are tasked with constraining excessive risk-taking that benefits management at the expense of shareholders (Sun and Liu 2014). _______________________________________________________________________________ Bing Yu*, Assistant Professor of Finance, School of Business, Meredith College, 3800 Hillsborough St., Raleigh, NC 27607, yubing@meredith.edu * Corresponding author Mary Jane Lenard, Professor of Accounting, School of Business, Meredith College, 3800 Hillsborough St., Raleigh, NC 27607, lenardmj@meredith.edu E. Anne York, Associate Professor of Economics, School of Business, Meredith College, 3800 Hillsborough St., Raleigh, NC 27607, yorka@meredith.edu Shengxiong Wu, Assistant Professor of Finance, School of Business, Texas Wesleyan University, Fort Worth, TX 76105, shwu@txwes.edu 1 Proceedings of World Business Research Conference 11 - 13 June 2015, Hotel Novotel Xin Qiao, Beijing, China, ISBN: 978-1-922069-78-8 Researchers have examined the effect of women in the boardroom and their impact on firm performance (Lenard et al. 2014; Schwartz-Ziv 2013; Srunidhi et al. 2011; Rhode and Packel 2010; Adams and Ferreira 2009; Campbell and Minguez-vera 2008; deLuis-Carnicer et al. 2008; Carter et al. 2003; Anastasopoulos et al. 2002; Adler 2001). Research by Catalyst found that in 2012, women were just 16.6 percent of the directors for Fortune 500 companies and that 10.3 percent of these firms had no female board members (Catalyst 2012). Catalyst also reported that in 2012, just 19.2 percent of nominating/corporate governance committee chairs were female. Looking specifically at banks, Landy (2014) reported that in 2014 there were roughly 100 bank holding companies in the U.S. with assets of more than $10 billion. In 2011, five of those companies had a female CEO – now only three do. Data from the Bureau of Labor Statistics show that the percentage of women employed in the banking industry has fallen from 68.4% in 2004 to 61% in 2013. Ross-Smith and Bridge (2008) noticed a similar “glacial effect” regarding the progress of women in corporate governance in Australia, and Shilton et al. (2010) reported that women are also underrepresented on corporate boards in New Zealand. Yet Bart and McQueen (2013) found that female directors achieved significantly higher scores than their male counterparts on a „Complex Moral Reasoning‟ (CMR) test. According to the authors, the CMR dimension involved making consistently fair decisions when competing interests were at stake. Studies of banks and financial institutions have specifically highlighted the impact of boards of directors and corporate governance during and after the global financial crisis. Wang and Hsu (2013) found that board size was negatively associated with risk events and that financial firms with a higher proportion of independent directors were less likely to suffer from fraud. They also found that a more diverse board could have an adverse impact on the board monitoring function. Peni and Vahamaa (2012) examined several corporate governance factors and found that banks with strong corporate governance had substantially higher stock returns in the aftermath of the market meltdown. Sun and Liu (2014) 2 Proceedings of World Business Research Conference 11 - 13 June 2015, Hotel Novotel Xin Qiao, Beijing, China, ISBN: 978-1-922069-78-8 studied audit committee effectiveness and found that banks with long board tenure audit committees had lower risk, while banks with busy directors on their audit committees had higher risk. Cooper and Uzun (2012) studied busy directors and bank risk and found that bank risk was positively related to multiple board appointments of bank directors, supporting the “busyness” hypothesis. Jiraporn et al. (2008) studied not only multiple-directorships but also multiple board committee memberships. They found that busier directors often serve on a higher number of board committees because they are more competent (supporting the “reputation” hypothesis). The authors also found that directors of regulated firms serve on a larger number of committees, and that women and ethnic minority directors held a larger number of board committee memberships. Pathan and Faff (2013) examined board structure in banks and the effect on performance. They included board size, independence, and gender diversity as the board characteristics. They also measured bank performance over three time periods – the pre-Sarbanes-Oxley Act (SOX) period, the post-SOX (2003 – 2006) period, and the global financial crisis period (20072011). They found that while gender diversity on the board of directors improved bank performance in the pre-SOX period, the positive effect of gender diminishes in both the post-SOX and the financial crisis periods. Thus, given these contradictory findings on board performance and corporate governance and the overall challenges of women leaders in the banking industry, it is important to investigate women‟s roles as both executives and board members, in order to examine the impact on the industry as it moves forward. Building on the work of Pathan and Faff (2013), our study analyzes the impact of gender in executive and board positions over the time period 2003 to 2011. We selected this time period because any specific committee memberships would reflect the rules defined under the Sarbanes-Oxley legislation, and also in order to consider the effect of the global financial crisis. If the board committees, especially after the SOX legislation, have an important role in monitoring firm performance in order to 3 Proceedings of World Business Research Conference 11 - 13 June 2015, Hotel Novotel Xin Qiao, Beijing, China, ISBN: 978-1-922069-78-8 reduce risk, and if women have increased their presence on these committees, then how do they contribute to the management of risk? In our paper, we look at the presence of women in leadership positions and the effect on bank risk. Specifically, we look at the percentage of women in executive positions, and the percentage of women directors on the audit committee and the corporate governance committee for our sample of banks during this time period. Our paper proceeds as follows. Section 2 contains a literature review and hypothesis development. Section 3 discusses our research methodology, and section 4 presents our results. Section 5 is our conclusion. 2 Literature review and hypothesis development Previous research on corporate boards has investigated the role of board size and board independence in mitigating risk. Klein (2002) found a negative relation between board independence and abnormal accruals. Cheng (2008) found that firms with larger boards have lower variability of corporate performance. On the other hand, previous studies also found an advantage to smaller boards. Jensen (1993) suggested that boards larger than seven or eight people are “less likely to function effectively and are easier for the CEO to control” (1993: 865). Group cohesiveness may also be a factor, as Evans and Dion (1991) reported a positive association between group cohesion and performance. Goodstein et al. (1994) found that largeness can significantly inhibit a board‟s ability to initiate strategic actions. Dalton et al. (1999) provide a summary of these competing viewpoints, where they found that the literature provided no consensus about the direction of the relationship between board size and firm performance. In addition to board size and composition, authors have studied the size and composition of board committees. Hamdan et al. (2013) investigated the relationship between audit committee characteristics and performance, and found that the size and structure of the audit committee had an effect on financial and stock performance for companies in Jordan. Thoopsamut and Jaikengkit (2009) found a negative relation between the average tenure of audit committees and quarterly earnings 4 Proceedings of World Business Research Conference 11 - 13 June 2015, Hotel Novotel Xin Qiao, Beijing, China, ISBN: 978-1-922069-78-8 management. However, Klein (1998), and Vafeas and Theodorou (1998) found no relationship between audit committees and firms‟ financial performance. Bruynseels and Cardinaels (2014) found that when CEOs appoint directors to audit committees from their social networks, there is a negative effect on variables that proxy for oversight quality. Researchers have studied the effect of gender diversity on the board of directors, or in executive positions, and the contribution to corporate performance. Srinidhi et al. (2011) studied gender-diverse boards in the U.S. using two measures of earnings quality. They found that firms with female directors exhibited higher earnings quality. Campbell and Minguez-vera (2008) studied Spanish companies from 1995-2000 and found that gender diversity on the board had a positive effect on firm value. Similarly, Barua et al. (2010) examined a sample of firms from 2004-2005 for the association between the quality of accruals and CFO gender. They found that companies with female CFOs had lower absolute discretionary accruals and lower absolute accrual estimation errors, resulting in better earnings quality for those firms. Peni and Vahamaa (2010) found that female CFOs followed more conservative earnings management strategies, testing S&P 500 firms in 2007. Ittonen and Peni (2012) examined gender differences of the audit engagement partner and the difference in audit pricing. In a study of three Nordic countries, they found that firms with female audit partners had significantly higher audit fees. The authors theorize that potential reasons include gender differences in risk tolerance, as well as female auditors‟ diligence, lower overconfidence, and higher level of preparation that could lead to a higher audit investment. Other authors used several different measures to show a link between gender diversity and corporate performance. Adler (2001) found a strong correlation between women-friendliness and firm profitability. In studying Fortune 500 companies from 1980 to 1998, he developed a scoring system to determine “women-friendly” firms as those firms who scored highest in employing women in the top 10 5 Proceedings of World Business Research Conference 11 - 13 June 2015, Hotel Novotel Xin Qiao, Beijing, China, ISBN: 978-1-922069-78-8 executive positions, the next 10 executive positions, and the board of directors. The profitability measures in his study were return on assets (ROA), return on sales (ROS), and return on equity (ROE). Carter et al. (2003) encountered a positive relationship between board diversity and firm value, proxied by Tobin‟s Q. In 2004, Catalyst examined the connection between gender diversity and financial performance, using a sample of Fortune 500 companies from 1996-2000. The study found that firms in the top quartile in terms of diversity achieved better financial performance, as measure by ROE and raw stock returns, than their lower-quartile counterparts (Catalyst, 2004). Schubert (2006) studied gender differences in risk attitudes and found that women were more pessimistic towards gains than men. In the context of risk management, however, women were found to have a comparative advantage with respect to diversification and communication tasks. The author noted that these results had implications on firm success because “a well-established cooperation of men and women at the senior management level appears recommendable for firms which strive for an optimization of their risk analysis and risk management” (p. 706). Kesner (1988) studied a sample of 250 Fortune 500 companies in 1983 for directors‟ characteristics and committee membership. She found that while women made up only a small percentage of board members (3.6%), a woman‟s odds of being on the audit committee were 1.78 to 1, compared to .575 to 1 for a man. However, a woman‟s odds of being on the compensation committee were .819 to 1, compared to 1.22 to 1 for a man. Yet these two committees are still two of the most prominent committees of the board. Kesner concludes that as long as some “degree of diversity” is present among members, it allows differing viewpoints to be heard, which may serve to strengthen the board. However, Kesner‟s study was done before 2002. We update her results, along with the previously described conflicting results specific to the banking industry, and examine gender diversity in two areas: on the executive team, and on specific committees of the board. Our hypotheses are as follows: 6 Proceedings of World Business Research Conference 11 - 13 June 2015, Hotel Novotel Xin Qiao, Beijing, China, ISBN: 978-1-922069-78-8 H1: Increasing gender diversity on the executive team is significantly associated with the variability of corporate performance. H2: Increasing gender diversity on specific committees of the board is significantly associated with the variability of corporate performance. In studies of multiple board memberships and board busyness, there are conflicting results. Fich and Shivdasani (2006) suggested a “busyness” hypothesis and found that firms in which a majority of outside directors hold three or more directorships are associated with weak corporate governance and weaker profitability. Cooper and Uzun (2012) specifically studied the impact of busy directors on bank risk, and found that bank risk was positively related to multiple board appointments. Sharma and Iselin (2012) studied the association between multiple-directorships and tenure of audit committee members and financial misstatements. They found a significant positive association between financial misstatements and both tenure and multiple-directorships in the post-SOX time period. They reasoned that independent audit committee members serving on multiple boards may be stretched too thinly to effectively perform their monitoring responsibilities. Chandar et al. (2012) studied what happens when there is overlap on the audit and compensation committees. They found that the effect is a non-linear relationship, and that when the overlapping percentage is 47 percent, the abnormal accruals are the lowest, implying the highest financial reporting quality at that point. Xie et al. (2003) examined the relationship between the audit committee and financial reporting quality. They found that board and audit committee members with corporate or financial backgrounds were associated with firms that had lower discretionary accruals. They found the same result when the board and audit committee met more frequently. Fama and Jensen (1983) reported results that support the “reputation hypothesis”, where the number of committee memberships signals director reputation. This hypothesis reasons that directors on multiple committees offer better advice and better monitoring than directors on only one committee. We 7 Proceedings of World Business Research Conference 11 - 13 June 2015, Hotel Novotel Xin Qiao, Beijing, China, ISBN: 978-1-922069-78-8 thus investigate whether female board members serving on more than one committee have an effect on bank risk. Our hypothesis is as follows: H3: A female director serving on multiple committees is significantly associated with the variability of corporate performance 3 Data and model development 3.1 Data Our sample consists of companies in the financial industry (SIC codes between 6000 and 6500) from the RiskMetrics database from 2003 to 2011. This database contains information on corporate boards of directors. Financial variables were collected from the Compustat database and CRSP database for the same years. We used multiple years of financial information in order to have a more accurate measure of financial performance. We excluded companies whose financial statement information was incomplete or unavailable on Compustat or CRSP. Our final sample consists of 616 firm-year observations, which represents 94 banks. 3.2 Model development Our dependent variable, SD_RETi,t, is the standard deviation of monthly stock return in each year. We use monthly stock return to eliminate daily stock price fluctuation and therefore standard deviation is a better risk measure (Cheng 2008). We include the following control variables to control for firmspecific factors such as operation efficiency, management effectiveness, and corporate governance quality. 8 Proceedings of World Business Research Conference 11 - 13 June 2015, Hotel Novotel Xin Qiao, Beijing, China, ISBN: 978-1-922069-78-8 Dependent Variable,t + β4LN_TAi,t + Dummy = α + β1LEVERAGEi,t + β2ROAi,t + β3Tobins_Qi,t β5Board_Variablesi,t + β6Female_Governancei,t + β7FCRSi,t + β8FCRS*Fi,t +Year (1) Our control variables are total debt ratio (LEVERAGE), return on assets (ROA), firm size that is measured by log of total assets (LN_TA), and Tobin’s_Q. We would expect that bigger, older, more diversified firms are likely to observe less variable performance (Cheng 2008). We would also expect that firms with lower profitability, as measured by ROA, would have higher variability of performance. We also include Tobin‟s Q as an independent variable. Tobin‟s Q is a proxy for growth computed as the sum of the market value of equity plus the book value of liabilities, divided by the book value of total assets (Pathan and Faff 2013). It is expected to be negatively associated with market variability. Our board variables are either board size (B_SIZE), or whether there is a CEO who is also the chairman of the board (CEO_CHAIR). In the model examining the women on the various board committees, we follow Cheng (2008), and examine whether the board size is an indicator of performance variability. Our variable, B_SIZE, is the log of the number of board members. Wang (2012) found that small boards give CEOs larger incentives and force them to bear more risk than larger boards. So a smaller board would imply more volatility or variability. However, other authors have found the opposite result (Jensen 1993; Goodstein et al. 1994). Therefore we have no prediction about the sign of the B_SIZE variable. Then, when we examine the percentage of women executives at the bank, we expect someone who is both CEO and Chairman of the Board (CEO_CHAIR) to exercise more power in decision-making. According to Cheng (2008), when CEOs become more powerful, firm performance may become more variable or less variable. Cheng uses this variable in order to distinguish agency problems of a powerful CEO from board size. We also use a dummy variable, FCRS, to represent the time period of the financial crisis, 2007 – 2011. FCRS is equal to one if year is between 2007 and 2011, 9 Proceedings of World Business Research Conference 11 - 13 June 2015, Hotel Novotel Xin Qiao, Beijing, China, ISBN: 978-1-922069-78-8 otherwise zero. We expect that there will be more variability of financial performance during this time. To examine female directors‟ role in bank risk during the financial crisis period, we add an interaction term FCRS*F which is FCRS dummy multiplied by female dummy, F. F is equal to one if there is a female director on a board, otherwise zero. We have several variables that measure female governance. Our first test variable, PCT_F_EXE represents the role of female executives. According to the RiskMetrics dataset we count the following eight positions - CEO, CFO, Chairman, COO, Executive VP, President, Senior VP, and Treasurer, as executive positions. PCT_F_EXE is number of females in the above positions at a bank divided by eight. We then measure the various board positions. We measure the percentage of women on two of the committees that comprise a monitoring role and could significantly affect bank risk. These two variables are represented as the percentage of female members of the audit committee (PCT_F_AUD) and the percentage of female members of the corporate governance committee (PCT_F_CG). We run all models using the two-stage system GMM approach, following Arellano and Bover (1995). This two-stage system GMM model treats all explanatory variables as endogenous and orthogonally uses lagged values as instruments. To correct the unobserved heterogeneity and omitted variable bias, we generate a match equation of the first differences of all variables and use the lagged value of independent variables to estimate models via GMM. Doing so treats all explanatory variables except firm size (LN_TA) and the financial crisis dummy (FCRS) as endogenous (Wintoki et al. 2012). We conduct the F-test and Hansen‟s J-test to check the reliability of estimation and validity of the instrument. 4 Results 4.1 Descriptive Statistics 10 Proceedings of World Business Research Conference 11 - 13 June 2015, Hotel Novotel Xin Qiao, Beijing, China, ISBN: 978-1-922069-78-8 Figures 1 through 4 represent the average percentage of women in executive and director positions in the banking industry over the time period of our sample. Figure 1 shows that the average percentage of female directors increased from just below 11 percent in 2003 to approximately 13 percent in 2012. At the same time, Figure 2 shows that the average percentage of women executives declined from approximately 7 percent to fewer than 2 percent. Figure 3 indicates that the percentage of women on the audit committee increased after 2004, moving from slightly more than 10 percent to more than 16 percent. Figure 4 shows that the percentage of women on the corporate governance committee has fluctuated, with the most recent average at 11 percent in 2011. [Insert Figures 1 through 4 here] Table 1, Panel A shows the descriptive statistics for our sample of banks. The minimum size of a board is 5 directors, while the maximum is 26 directors, with a median of 12 directors. When we examine the number of members of the audit committees, there is a maximum of 9 members on such a committee, with an average of just over 4 members. The average size of the corporate governance committee is approximately 4 members, with a maximum of 12 members. On average, the percentage of women directors is 12.1%, percentage of women on the audit committee is 13.7%, and percentage of women on the corporate governance committee is 11.5%. In contrast, the average percentage of women executives is 3.3%. The descriptive statistics in Table 1, Panel B cover the financial variables in our model. The average standard deviation of stock return (SD_RET) is 9.2%, the standard deviation of market-adjusted stock return (SD_MKT_ADJ_RET) is 8%. The leverage (LEVERAGE) has a mean (median) of 8.7% (7.7%). The mean (median) ROA for the time period of our sample is 0.6% (0.9%), and the mean (median) of Tobin‟s Q is 1.052 (1.046). Size, measured as the log of total assets (LN_TA), has a mean (median) of 9.78 (9.38). 11 Proceedings of World Business Research Conference 11 - 13 June 2015, Hotel Novotel Xin Qiao, Beijing, China, ISBN: 978-1-922069-78-8 [Insert Table 1 here] Table 2 shows the Pearson pair-wise sample correlations between variables. The correlation between the percentage of women on the audit and corporate governance committees (PCT_F_AUD and PCT_F_CG) and the financial variables of size and board size is positive and significant. This is to be expected because larger banks would have larger boards. SD_RET is negatively correlated with ROA, Tobin‟s Q, SIZE and B_SIZE, indicating that smaller banks with lower ROA and Tobin‟s Q reflect higher risk. [Insert Table 2 here] 4.2 Regression Results Table 3 shows the results of the model representing women executives and bank risk. Consistent with literature, ROA, Tobin‟s Q, and firm size (LN_TA) are negatively associated with bank risk while LEVERAGE and CEO_CHAIR are positively related to variability of bank stock return. We find that the percent of women executives (PCT_F_EXE) is positively associated with the variability of bank performance. For every one percentage point increase in the percent of female executives, the variability of return increases by 0.67 percent, all else held constant. The significant F-test shows that the model is well fitted and the insignificant Hansen J-statistic suggests that the instruments are valid in the two-stage system GMM model. [Insert Table 3 here] We report the results of our tests for the relation between women directors and bank risk in Table 4. While all controlling variables are consistent with the literature, we find that board size (B_SIZE) is positively associated with volatility of bank stock return. This finding is in line with previous studies that assert large boards have lower function efficiency (Jensen 1993, Evans and Dion 1991, and Goodstein et al 1994). We also find that both percentage of women on the audit committee (PCT_F_AUD) and 12 Proceedings of World Business Research Conference 11 - 13 June 2015, Hotel Novotel Xin Qiao, Beijing, China, ISBN: 978-1-922069-78-8 percentage of women on the corporate governance committee (PCT_F_CG) are negatively related to volatility of bank stock return. For every ten percentage point change in the percent of female directors on the audit (corporate governance) committee, the variability of stock return decreases by 0.16 (0.63) percent, respectively, all else held constant. While the positively significant FCRS dummy indicates that bank risks are higher during the financial crisis, the negatively significant interaction term FCRS*F shows that female directors‟ role in risk reduction is more pronounced during financial crisis period. In testing our sample, we found that the percentage of women on the audit committee increased steadily from 2003 to 2011 as shown in Figure 3. Based on the fact that there are more women on the audit committee, our results support the literature which shows that women have lower risk tolerance (Steffensmeier et al. 2013; Byrnes et al. 1999), and that more diverse teams are more diligent in their duties (Ittonen and Peni 2012; Schwartz-Ziv 2013). It also supports findings by Adams and Ferreira (2009) that women are more likely to join monitoring committees, and as such, gender diverse boards devote more effort to monitoring. Next, we examine the impact of busy women directors on bank risk. Table 5 reports the test results. We measure busy women directors using percentage of women directors on more than one committee (PCT_F_MULTI_COM). The coefficient of PCT_F_MULTI_COM is negatively significant, indicating that busier women directors are more likely to be related to lower bank risk. This finding is in line with Chandar et al (2012) and Fama and Jensen (1983), supporting the “reputation hypothesis”. [Insert Table 4 and Table 5 here] 4.3 Additional tests We run two additional tests to examine the robustness of our models. In order to remove the impact of market factors on firm performance variability, we calculate the market-adjusted return for each firm by subtracting the monthly S&P 500 index return from firm return. Our dependent variable, 13 Proceedings of World Business Research Conference 11 - 13 June 2015, Hotel Novotel Xin Qiao, Beijing, China, ISBN: 978-1-922069-78-8 SD_MKT_ADJ_RET, is the standard deviation of monthly market-adjusted stock return. As another robustness test, we also run model (1) by using a measure for idiosyncratic risk as a dependent variable. While the standard deviation of stock return measures total risk, it is the idiosyncratic risk that a company‟s executives or board members are able to influence because total risk includes two components, systematic risk and idiosyncratic risk. We use a single-index market model to estimate the total risk, which is the standard deviation of monthly stock returns. The idiosyncratic risk is the standard deviation of the residual in the following model: (2) where βi is systematic risk and Rm is the stock market return using an equally-weighted market index. Table 6 reports the results of these additional tests. In both regressions, the coefficients of percentage of females on the audit and corporate governance committees (PCT_F_AUD and PCT_F_CG) are negatively significant at the 1% level, indicating that having more women on audit or corporate governance committees is negatively associated with firm risk as measured by standard deviation of market-adjusted return or the idiosyncratic risk variable. [Insert Table 6 here] 5 Conclusion This paper examines the role of women in the banking industry and the impact on bank risk. Specifically, we look at the percentage of women in executive positions and the percentage of women in various board positions, and the impact on variability of stock return. We examine a sample of banks from the time period of 2003 – 2011. This time period includes the enactment of the SOX legislation and the global financial crisis. The objective of our study was to examine the role of diversity, both in the executive suite and in the boardroom. Our findings support the statistics that the number of 14 Proceedings of World Business Research Conference 11 - 13 June 2015, Hotel Novotel Xin Qiao, Beijing, China, ISBN: 978-1-922069-78-8 women executives in banking positions is declining. For the early time period in our sample, the percentage of women executives positively affects bank risk. However, during the financial crisis, the presence of women executive reduces bank risk. On the other hand, for the full time period of our sample, as the percentage of women on the audit committee and corporate committee increases, the bank risk decreases. Our research findings support studies that indicate that women follow a more conservative approach to financial management (Barua et al. 2010; Peni and Vahamaa 2010) and that they have a more diligent approach to the monitoring role (Ittonen and Peni 2012), through membership on the auditing committee and corporate governance committee. Our findings also support the “reputation hypothesis” regarding board busyness (Chandar et al 2012; Fama and Jensen 1983). As the percentage of women on multiple committees in our sample increased, the bank risk decreased. Our results show that women play an important role in the risk management of the banking industry, and that increased gender diversity of the board and participation on board committees is effective in reducing bank risk. More research could be conducted to examine what policy choices about board structure are most effective in improving and monitoring corporate performance. 15 Proceedings of World Business Research Conference 11 - 13 June 2015, Hotel Novotel Xin Qiao, Beijing, China, ISBN: 978-1-922069-78-8 .11 .115 .12 .125 .13 Figure 1 Percent of Women Directors 2002 2004 2006 2008 Data Year - Fiscal 2010 2012 16 Proceedings of World Business Research Conference 11 - 13 June 2015, Hotel Novotel Xin Qiao, Beijing, China, ISBN: 978-1-922069-78-8 .05 .04 .03 .02 mean_pct_w_mg .06 .07 Figure 2 Percent of Women Executives 2002 2004 2006 2008 Data Year - Fiscal 2010 2012 17 Proceedings of World Business Research Conference 11 - 13 June 2015, Hotel Novotel Xin Qiao, Beijing, China, ISBN: 978-1-922069-78-8 .1 .12 .14 .16 Figure 3 Percent of Women Directors in Audit Committee 2002 2004 2006 2008 Data Year - Fiscal 2010 2012 18 Proceedings of World Business Research Conference 11 - 13 June 2015, Hotel Novotel Xin Qiao, Beijing, China, ISBN: 978-1-922069-78-8 .12 .11 .1 .09 mean_pct_f_cg .13 .14 Figure 4 Percent of Women Directors in Corporate Governance Committee 2002 2004 2006 2008 Data Year - Fiscal 2010 2012 Table 1 Descriptive Statistics Panel A. Board Structure of Banks No. of Director Percent of Woman Directors Audit Committee Size Percent of Women on Audit Com CG Committee Size Percent of Women on CG Com Percent of Women Executives Mean 12.609 0.121 4.341 SD 2.978 0.079 1.112 0.137 3.930 0.115 0.033 0.159 1.935 0.152 0.066 Min Median 5 12 0 0.111 1 4 Max 26 0.462 9 N 616 616 616 0 4 0 0 0.667 12 0.667 0.25 616 616 561 616 Min Median 0.019 0.073 0.018 0.061 0.000 0.077 -0.162 0.009 0.892 1.046 7.435 9.386 Max 0.449 0.439 0.558 0.037 1.314 14.633 N 614 614 616 616 616 616 0 0 0 0 Panel B. Financial Characteristics of Banks SD_RET* SD_MKT_ADJ_RET LEVERAGE ROA Q LN_TA Mean 0.092 0.080 0.087 0.006 1.052 9.786 SD 0.063 0.059 0.070 0.014 0.076 1.556 19 Proceedings of World Business Research Conference 11 - 13 June 2015, Hotel Novotel Xin Qiao, Beijing, China, ISBN: 978-1-922069-78-8 * Variables are defined in model development section 20 Proceedings of World Business Research Conference 11 - 13 June 2015, Hotel Novotel Xin Qiao, Beijing, China, ISBN: 978-1-922069-78-8 Table 2 Sample Correlations PCT_F_AUD PCT_F_CG PCT_F_EXE SD_RET LEVERAGE ROA Q PCT_F_AUD 1 0.1491* 0.1213* -0.058 -0.0339 -0.0189 -0.0086 PCT_F_CG PCT_F_MG 1 0.013 -0.011 -0.024 -0.001 0.021 1 -0.0968* 0.0049 0.0963* 0.1117* SD_RET LEVERAGE 1 0.015 -0.5943* -0.5720* 1 -0.016 -0.1200* SIZE 0.1931* 0.2121* 0.1610* -0.055 0.1924* B_SIZE 0.1527* 0.2128* 0.0602 -0.1132* 0.007 *denotes 5% significance level. All variables are defined in model development section. ROA 1 0.5021* 0.065 0.0855* Q 1 0.1273* 0.0085 SIZE B_SIZE 1 0.3874* 1 Proceedings of World Business Research Conference 11 - 13 June 2015, Hotel Novotel Xin Qiao, Beijing, China, ISBN: 978-1-922069-78-8 Table 3 Women Executives and Bank Risk Dependent Var SD_RET SD_RETt-1 0.055** LEVERAGE 0.182*** ROA -3.931*** Q -0.323*** LN_TA -0.007*** CHAIR_CEO 0.006*** PCT_F_EXE 0.067** FCRS 0.010*** FCRS*W -0.183*** CONSTANT 0.486*** Year Dummy Yes F-Stat 182.11*** Hansen J-Stat 34.54(0.22) N 510 * significant at 10%; ** significant at 5%; *** significant at 1% Dependent Variable,t = α + β1LEVERAGEi,t + β2ROAi,t + β3Tobins_Qi,t + β4LN_TAi,t + β5CEO_CHAIRi,t +β6Pct_F_EXEi,t + β7FCRSi,t + β8FCRS*Wi,t Dependent Variable = standard deviation of monthly stock return (SD_RET) or standard deviation of monthly market-adjusted stock return (SD_MKT_ADJ_RET). LEVERAGE = Long-term debt / Total assets ; ROA = return on assets, Tobins_Q = (mkt value of equity + book value of liabilities)/book value of Total assets; LN_TA = log of Total assets; CEO_CHAIR = 1 if someone is the CEO and Chairman of the Board, 0 otherwise. Pct_F_EXE= percentage of female executives on the executive positions, including CEO, CFO, Chairman, COO, Executive VP, President, Senior VP, and Treasurer. FCRS is a dummy variable indicating the time period of the financial crisis, 2007 – 2011. FCRS*W is an interaction term between FCRS and a dummy W that equals to one if there is at least one female on the executive positions, otherwise zero. Proceedings of World Business Research Conference 11 - 13 June 2015, Hotel Novotel Xin Qiao, Beijing, China, ISBN: 978-1-922069-78-8 Table 4 Women Directors and Bank Risk Dependent Var SD_RET SD_RET SD_RET SD_RET SD_RETt-1 0.164*** 0.128*** 0.133*** 0.144*** LEVERAGE 0.140*** 0.146*** 0.129*** 0.098*** ROA -2.820*** -3.533*** -3.163*** -3.166*** Q -0.345*** -0.296*** -0.300*** -0.312*** LN_TA -0.003*** -0.004*** -0.004*** -0.001 B_SIZE 0.037*** 0.026*** 0.035*** 0.032*** PCT_F_DIRECTOR 0.004 0.049*** PCT_F_AUD -0.010* -0.015*** PCT_F_CG -0.039*** -0.053*** FCRS 0.018*** 0.019*** 0.014*** 0.006** FCRS*F -0.023*** -0.032*** -0.020*** -0.029*** CONSTANT 0.379*** 0.373*** 0.500*** 0.560*** Year Dummy Yes Yes Yes Yes F-Stat 2168*** 1631.03*** 4273.31*** 6271.75*** Hansen J-Stat 24.73(1.00) 37.12(0.56) 36.54(0.84) 19.88(0.99) N 479 510 510 479 * significant at 10%; ** significant at 5%; *** significant at 1% Dependent Variable,t = α + β1LEVERAGEi,t + β2ROAi,t + β3Tobins_Qi,t + β4LN_TAi,t + β5B_SIZEi,t + β6Pct_F_DIRECTORi,t + β7Pct_F_Audi,t + β8Pct_F_CGi,t + β9FCRSi,t + β10FCRS*Fi,t Dependent Variable = standard deviation of monthly stock return (SD_RET). LEVERAGE = Longterm debt / Total assets ; ROA = return on assets, Tobins_Q = (mkt value of equity + book value of liabilities)/book value of Total assets; LN_TA = log of Total assets; B_SIZE = Log of number of directors; Pct_F_DIRECTOR= percentage of female directors on the board; Pct_F_Aud = percentage of female directors on the audit committee. Pct_F_CG = percentage of female directors on the corporate governance committee. FCRS is a dummy variable indicating the time period of the financial crisis, 2007 – 2011. FCRS*F is an interaction term between FCRS and a dummy F that equals to on if there is at least one female director on the board, otherwise zero. 23 Proceedings of World Business Research Conference 11 - 13 June 2015, Hotel Novotel Xin Qiao, Beijing, China, ISBN: 978-1-922069-78-8 Table 5 Busy Women Directors and Bank Risk Dependent Var SD_RET SD_RETt-1 0.163*** LEVERAGE 0.114*** ROA -2.932*** Q -0.298*** LN_TA -0.002*** PCT_F_AUD -0.017*** PCT_F_CG -0.043*** PCT_F_MULTI_COM -0.020* B_SIZE 0.031*** FCR 0.022*** FCR*F -0.022*** CONTANT 0.337*** Year Dummy Yes F-Stat 1081.83*** Hansen J-Stat 0.99(0.61) N 479 * significant at 10%; ** significant at 5%; *** significant at 1% Dependent Variable,t = α + β1LEVERAGEi,t + β2ROAi,t + β3Tobins_Qi,t + β4LN_TAi,t + β5B_SIZEi,t + β6Pct_F_Audi,t + β7Pct_F_CGi,t + β8Pct_F_MULTI_COMi,t + β9FCRSi,t + β10FCRS*Fi,t Dependent Variable = standard deviation of monthly stock return (SD_RET). LEVERAGE = Longterm debt / Total assets ; ROA = return on assets, Tobins_Q = (mkt value of equity + book value of liabilities)/book value of Total assets; LN_TA = log of Total assets; B_SIZE = Log of number of directors; Pct_F_Aud = percentage of female directors on the audit committee. Pct_F_CG = percentage of female directors on the corporate governance committee. Pct_F_MULTI_COM = percentage of female directors who serve on more than one committees on a board. FCRS is a dummy variable indicating the time period of the financial crisis, 2007 – 2011. FCRS*F is an interaction term between FCRS and a dummy F that equals to on if there is at least one female director on the board, otherwise zero. 24 Proceedings of World Business Research Conference 11 - 13 June 2015, Hotel Novotel Xin Qiao, Beijing, China, ISBN: 978-1-922069-78-8 Table 6 Robustness Tests Dependent Var SD_MKT_ADJ_RET IDI_RISK SD_MKT_AJ_RETt0.090*** 1 IDI_RISK 0.100*** LEVERAGE 0.162*** 0.156*** ROA -3.259*** -3.195*** Q -0.217*** -0.243*** LN_TA -0.002*** -0.002*** PCT_F_AUD -0.006** -0.006** PCT_F_CG -0.057*** -0.059*** B_SIZE 0.051*** 0.049*** FCR 0.020*** 0.020*** FCR*F -0.029*** -0.029*** CONTANT 0.201*** 0.229*** Year Dummy Yes Yes F-Stat 3829.7*** 1177.98*** Hansen J-Stat 0.11(0.947) 0.26(0.88) N 479 479 * significant at 10%; ** significant at 5%; *** significant at 1% Dependent Variable,t = α + β1LEVERAGEi,t + β2ROAi,t + β3Tobins_Qi,t + β4LN_TAi,t + β5B_SIZEi,t + β6Pct_F_Audi,t + β7Pct_F_CGi,t + β8FCRSi,t + β9FCRS*Fi,t SD_MKT_AJ_RET = standard deviation of monthly market-adjusted stock return, IDI_RISK=idiosyncratic risk measure which is the standard deviation of the error terms of total risk. LEVERAGE = Long-term debt / Total assets ; ROA = return on assets, Tobins_Q = (mkt value of equity + book value of liabilities)/book value of Total assets; LN_TA = log of Total assets; B_SIZE = Log of number of directors; Pct_F_Aud = percentage of female directors on the audit committee; Pct_F_CG = percentage of female directors on the corporate governance committee; FCRS is a dummy variable indicating the time period of the financial crisis, 2007 – 2011; FCRS*F is an interaction term between FCRS and a dummy F that equals to on if there is at least one female director on the board, otherwise zero. 25 Proceedings of World Business Research Conference 11 - 13 June 2015, Hotel Novotel Xin Qiao, Beijing, China, ISBN: 978-1-922069-78-8 References Adams, R.B., and Ferreira, D. (2009), “Women in the boardroom and their impact on governance and performance”, Journal of Financial Economics, Vol. 94, pp. 291-309. Adler, R.D. (2001), “Women in the executive suite correlate to high profits”, Glass Ceiling Research Center, http://www.w2t.se/se/filer/adler_web.pdf. Anastasopoulos, V., Brown, D.A.H., and Brown, D.L. (2002). “Women on Boards: Not Just the Right Thing, but the „Bright‟ Thing”, The Conference Board of Canada. Bart, C., and McQueen, G. (2013), “Why women make better directors”, International Journal of Business Governance and Ethics, Vol. 8, No. 1, pp. 93-99. Barua, A., Davidson, L.F., Rama, D.V., and Thiruvadi, S. (2010), “CFO gender and accruals quality”, Accounting Horizons, Vol. 24, No. 1, pp. 25-39. Bruynseels, L., and Cardinaels, E. (2014), “The audit committee: Management watchdog or personal friend of the CEO?”, The Accounting Review, Vol. 89, No. 1, pp. 113-145. Byrnes, J.P., Miller, D.C., and Schafer, W.D. (1999), “Gender differences in risk taking: A metaanalysis”, Psychological Bulletin, Vol. 125, pp. 367-383. Campbell, K., and Minguez-vera, A. (2008), “Gender diversity in the boardroom and firm financial performance”, Journal of Business Ethics, Vol. 83, No. 3, pp. 435-451. Carter, D.A., Simkins, B.J., and Simpson, W.G. (2003), “Corporate governance, board diversity, and firm value”, The Financial Review, Vol. 38, pp. 33-53. Catalyst (2004), “The bottom line: Connecting corporate performance and gender diversity”, Catalyst Publication Code D58, New York, pp. 1-28. Catalyst (2012), “2012 Catalyst Census: Women Board Directors”, Catalyst, New York. Chandar, N., Chang, H., and Zheng, X. (2012), “Does overlapping membership on audit and compensation committees improve a firm‟s financial reporting quality?”, Review of Accounting and Finance, Vol. 11, No. 2, pp. 141-165. Chava, S., and Purnanandam, A. (2010), “CEOs versus CFOs: Incentives and corporate policies”, Journal of Financial Economics, Vol. 97, No. 1, pp. 263-278. Cheng, S. (2008), “Board size and the variability of corporate performance”, Journal of Financial Economics, Vol. 87, pp. 157-176. Cooper, E., and Uzun, H. (2012), “Directors with a full plate: the impact of busy directors on bank risk”, Managerial Finance, Vol. 38, No. 6, pp. 571-586. 26 Proceedings of World Business Research Conference 11 - 13 June 2015, Hotel Novotel Xin Qiao, Beijing, China, ISBN: 978-1-922069-78-8 Dalton, D.R., Daily, C.M., Johnson, J.L., and Ellstrand, A.E. (1999), “Number of directors and financial performance: A meta-analysis”, Academy of Management Journal, Vol. 42, No. 6, pp. 674-686. de Luis-Carnicer, P., Martinez-Sanchez, A., Perez-Perez, M, and Vela-Jimenez, M.J. (2008), “Gender diversity in management: Curvilinear relationships to reconcile findings”, Gender in Management: An International Journal, Vol. 23, No. 8, pp. 583-597. Evans, C.R., and Dion, K.L. (1991), “Group cohesion and performance: A meta-analysis”, Small Group Research, Vol. 22, pp. 175-186. Fama, E., and Jensen, M. (1983), “The separation of ownership and control”, Journal of Law & Economics, Vol. 26, pp. 301-25. Fich, E.M., and Shivdasani, A. (2006), “Are busy boards effective monitors?”, The Journal of Finance, Vol. 41, No. 2, pp. 689-723. Francis, B., Hasan, I., and Wu, Q. (2013), “The impact of CFO gender on bank loan contracting”, Journal of Accounting, Auditing & Finance, Vol. 28, No. 1, 53-78. Francis, B., Hasan, I., Park, J.C., and Wu, Q. (2014), “Gender differences in financial reporting decision-making: Evidence from accounting conservatism”, Contemporary Accounting Research, forthcoming. Goodstein, J., Gautam, K., and Boeker, W. (1994), “The effects of board size and diversity on strategic change”, Strategic Management Journal, Vol. 15, pp. 241-250. Hamdan, A.M., Sarea, A.M., and Reda Reyad, S.M. (2013), “The impact of audit committee characteristics on the performance: Evidence from Jordan”, International Management Review, Vol. 9, No. 1, pp. 32-41. Ittonen, K. and Peni, E. (2012), “Auditor‟s gender and audit fees”, International Journal of Auditing, Vol. 16, No. 1, pp. 1-18. Jensen, M.C. (1993), “The modern industrial revolution, exit, and the failure of internal control systems”, Journal of Finance, Vol. 48, pp. 831-880. Jiraporn, P., Singh, M., and Lee, C.I. (2009), “Ineffective corporate governance: Director busyness and board committee memberships”, Journal of Banking & Finance, Vol. 33, pp. 819-828. Kesner, I.F. (1988), “Directors‟ characteristics and committee membership: An investigation of type, occupation, tenure, and gender”, Academy of Management Journal, Vol. 31, No. 1, pp. 66-84. Klein, A. (2002), “Audit committee, board of director characteristics, and earnings management”, Journal of Accounting and Economics, Vol. 33, pp. 375-400. 27 Proceedings of World Business Research Conference 11 - 13 June 2015, Hotel Novotel Xin Qiao, Beijing, China, ISBN: 978-1-922069-78-8 Klein, A. (1998), “Firm performance and board committee structure”, Journal of Law and Economics, Vol. 41, pp. 275-299. Landy, H. (2014), “The incredible shrinking statistic: Female bank CEOs”, American Banker, http://www.americanbanker.com/bankthink/the-incredible-shrinking-statistic-female-bankceos-1068188-1.html?wib . Lenard, M.J., Yu, B., York, E.A., and Wu, S. (2014), “Impact of Board Gender Diversity on Firm Risk”, Managerial Finance, Vol. 40, No. 8. Pathan, S., and Faff, R. (2013), “Does board structure in banks really affect their performance?”, Journal of Banking & Finance, Vol. 37, pp. 1573-1589. Peni, E., and Vahamaa, S. (2012), “Did good corporate governance improve bank performance during the financial crisis?”, Journal of Financial Services Research, Vol. 41, No. 1-2, pp. 19-35. Peni, E., and Vahamaa, S. (2010), “Female executives and earnings management”, Managerial Finance, Vol. 36, No. 7, pp. 629-645. Ross-Smith, A. and Bridge, J. (2008), “„Glacial at best‟: women‟s progress on corporate boards in Australia”, in Vinnicombe, S., Singh, V., Burke, R.J., Bilmoria, D. and Huse, M. (Eds), Women on Corporate Board of Directors: International Research and Practice, Edward Elgar Publishers, Cheltenham. Rhode, D. L. and Packel, A. K. (2010), “Diversity on corporate boards: How much difference does difference make?”, working paper, Rock Center for Corporate Governance, Stanford, CA. Schubert, R. (2006), “Analyzing and managing risks – on the importance of gender difference in risk attitudes”, Managerial Finance, Vol. 32, pp. 706-715. Schwartz-Ziv, M. (2013), “Does the Gender of Directors Matter?”, SSRN Working Paper Series. Sharma, V.D., and Iselin, E.R. (2012), “The association between audit committee multipledirectorships, tenure, and financial misstatements”, Auditing: A Journal of Practice & Theory, Vol. 31, No. 3, pp. 149-175. Shilton, J., McGregor, J. and Tremaine, M. (2010), “Feminizing the boardroom: a study of the effects of corporatization on the number and status of women directors in New Zealand companies”, Gender in Management: An International Journal, Vol. 25, No. 4, pp. 275-84. Srinidhi, B., Gul, F.A., and Tsui, J. (2011), “Female directors and earnings quality”, Contemporary Accounting Research, Vol. 28, No. 5, pp. 1610-1644. 28 Proceedings of World Business Research Conference 11 - 13 June 2015, Hotel Novotel Xin Qiao, Beijing, China, ISBN: 978-1-922069-78-8 Steffensmeier, D.J., Schwartz, J., and Roche, M. (2013), “Gender and twenty-first-century corporate crime: Female involvement and the gender gap in Enron-era corporate frauds”, American Sociological Review, Vol. 78, No. 3, pp. 448-476. Sun, J., and Liu, G. (2014), “Audit committees‟ oversight of bank risk-taking”, Journal of Banking & Finance, Vol. 40, No. 1, pp. 376-387. “Table 14: Employed Persons by Detailed Industry and Sex, 2004 Annual Averages.” In Labor Force Statistics from the Current Population Survey. Available at: http://www.bls.gov/cps/wlftable14-2005.pdf. Accessed: 08/14/2014. “Table 18: Employed Persons by Detailed Industry, Sex, Race, Hispanic or Latino Ethnicity.” In Labor Force Statistics from the Current Population Survey. Available at: http://www.bls.gov/cps/cpsaat18.pdf. Accessed: 08/14/2014. Thoopsamut, W., and Jaikengkit, A. (2009), “The relationship between audit committee characteristics, audit firm size and earnings management in quarterly financial reports of companies listed in the stock exchange of Thailand”. Selected contributions from the 8th Global Conference: Firenze University Press. U.S. House of Representatives. (2002). “The Sarbanes-Oxley Act of 2002”, Public Law 107-204 [H.R. 3763]. Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office. Vafeas, N., and Theodorou, E. (1998). “The association between board structure and firm performance in the UK”, British Accounting Review, Vol. 30, pp. 383-407. Wang, C-J. (2012), “Board size and firm risk-taking”, Review of Quantitative Finance and Accounting, Vol. 38, No. 4, pp. 519-542. Wang, T., and Hsu, C. (2013). “Board composition and operational risk events of financial institutions”, Journal of Banking & Finance, Vol. 37, pp. 2042-2051. Xie, B., Davidson III, W.N., and DaDalt, P.J. (2003), “Earnings management and corporate governance: The role of the board and the audit committee”, Journal of Corporate Finance, Vol. 9, No. 3, pp. 295-316. 29