Proceedings of 3rd European Business Research Conference

advertisement

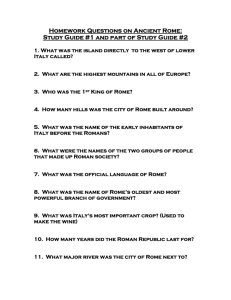

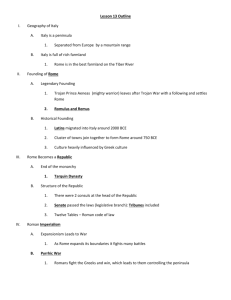

Proceedings of 3rd European Business Research Conference 4 - 5 September 2014, Sheraton Roma, Rome, Italy, ISBN: 978-1-922069-59-7 Modeling the Effect on Discretionary Income of a Private Good Higher Education System Kirk Douglas Johnson* Educational polic y in the United States since the late 1980s has actively encouraged larger percent ages of middle and lower income youths to attend university following secondary school. This increase in participation rates is simultaneous to redefining higher education as a private rather than public good. Funding sources for many institutions shifted away from government and public agencies and ont o students, their families, and the debt mark et. Escalating costs have resulted in more than one t rillion dollars of educational debt. This represents a long -term reduction in living standards for those carrying larger than median debt loads. Pe rsonal Finance defines credit wort hiness and indebtedness ratios using Gross Income instead of Net Income. It is argued that this measure mask s the level of indebtedness as US households have experienced more than a 60% reduction in relative discretionary incomes during the same general measurement period. The author uses an Opport unity S ets Model to describe the transformation through these simultaneous forces. Educational indebtedness will delay traditional “adult” independence, home ownership, and wealth accumulation. This delay is particularly long (more than t went y years) among the lowest resource households. This emmizerization of a generational cohort will have long-term consequences. The results of this convergence are of particular note as the US model for higher education funding is being exported to other nations, where educational debt figures are becoming a public concern. 1. Introduction Opportunity Set Models are an interesting overlay of competing schools of thought. In the modern US mainstream, Opportunity Sets refer to the two -axis model of Chapter 2 in Principles of Economics textbooks. It represents a frontier assuming efficiency (itself a debated term) and the full application of available resources to the endeavors represented by the axes. To promote “realism” it can be bowed to allow for specialized resources with different technological capacities. The limits of productive capacity fall on the production possibility frontier [PPF] and the slope of the line represents the ratio of sacrifice between resources used to generate changing levels of outputs; opportunity cost. Wisconsin Institutionalists have taken the same model, but added conditional elements. Not only specialized resources define economic Agents‟ PPFs, but available choices are defined by the rules structure. These rules could be limiting in nature. US markets do not permit buying or selling of kidneys even if someone perceives their second as superfluous. Sometimes they are widening. _____________ *Kirk Douglas Johnson, Goldey-Beacom College, USA. Email: johnsok@gbc.edu Proceedings of 3rd European Business Research Conference 4 - 5 September 2014, Sheraton Roma, Rome, Italy, ISBN: 978-1-922069-59-7 By defining legal tender and maintaining its stability, the US Government has reduced transactions costs for billions of people, the majority of which are not inside US political borders. The conflicting nature of mutually exclusive paradigms is less pronounced in this case. Essentially, the Institutionalists perceive in their competitors a simplified model that has assumed a specific socio-legal-economic nexus that fails to account for the complexity of impacts such nexus-forms have on economic outcomes. Neoclassical Economists see the Institutionalists as pseudo-scientists by insisting unquantifiable social organizations beyond the market pre-determine market outcomes. At the risk of alienating both groups, this paper will use a hybridized approach. Every agent has a choice set defined in the extant economy. This is a function of capital, human capital, and endowments (C, H, and E). financial and personal resources of the agent. PPF represents both the Someone aware of financial calculations and the time value of money is more likely to select intertemporal allocations that minimize waste (inefficiency). If they lack many financial resources, they are relatively limited in their ability to have choices available compared to someone with greater financial resources. Even if the greater resource agent is unable to understand the link between value in the distant future relative to today, they can afford to be inefficient and still maintain greater consumption levels across time periods. If we relax the assumption of constant economic conditions, then changes in conditions could change the available choices. For some agents these changes will be limiting while others will be widening. Choice Set for A = f[C A , HA , EA , and conditions] Choice Set for B = f[C B, HB, EB, and conditions] Proceedings of 3rd European Business Research Conference 4 - 5 September 2014, Sheraton Roma, Rome, Italy, ISBN: 978-1-922069-59-7 As A and B exchange goods and services, conditional changes may alter the relative size of each choice set. For example, if A sells bottled water in a community hit by the loss of community operated drinking water systems, conditions shift the relative value of bottled water. A can secure greater compensation as measured by B‟s output. The Choice Set of A becomes relatively larger post-event as B‟s shrinks. If a regulatory agent intervenes and limits the pricing power for bottled water, A will perceive a non-market intervention that limits her set of future choices by limiting her command for resources today. B will be the recipient of benefits even if they do not recognize them. They may only perceive a relatively unchanged choice set. Intervention into markets becomes a matter of selective perception. In this example, A would interpret regulatory action as a change in the rules adversely affecting their range of choices. B potentially sees the regulatory action as preserving the status quo as regards market outcomes and existing choice sets. As long as agents believe that any deviation from the status quo is newly minted government intervention, then any rule changes need to overcome the inertia of social approbation. Three secular trends have been altering choice sets by conditionally dependent sequences. Each will be described in isolation. They will be mapped onto the choice set model by indicating both the limiting and widening nature of each. Finally, the three will be combined to assess the impact o n specific groups of A‟s and B‟s. Every exchange is couched in ubiquitous sets of rules and conditions. To change “the rules” is not intervention. It is merely realigning which sets of agents have limiting and widening opportunity sets under the new socio-legal-economic nexus. Proceedings of 3rd European Business Research Conference 4 - 5 September 2014, Sheraton Roma, Rome, Italy, ISBN: 978-1-922069-59-7 2. Trend One: the delay of adulthood In a remarkable transition since 1980, US teenagers have been granted a 22% extension of childhood. It has been the explicit policy of at all levels of government to increase the proportion of students competing high school. Simultaneously, funding to primary and secondary education has been threatened unless demonstrative progress is made in generating “college ready” graduates. Vocational education (career -training starting at ages 14-18) designed to produce “work ready” graduates is being deemphasized through the power of the purse strings. We see this shift in educational policy in such statements as: “[T]he Obama administration's recently released proposal for rewriting the No Child Left Behind (NCLB) Act of 2001 calls for doing away with the 2014 goal of 100 percent proficiency in reading and math in favor of getting „all students college- and careerready‟...” [Paulson 2010] “[We]'ll foster what are called early college high schools that allow students to earn a high school diploma and an associate's degree or college credit at the same time. We want to learn from successful charter schools, where students can take advanced and college-level courses.” [Obama 2010] As a result of enacting and enforcing education rules is substantial change to generational opportunities. A2: young adults see the de-emphasis of physical and relatively low-skill through social cues and falling wages in those fields. labor Proceedings of 3rd European Business Research Conference 4 - 5 September 2014, Sheraton Roma, Rome, Italy, ISBN: 978-1-922069-59-7 A1: parents of young adults see reduced choice sets and search for alternative routes to adulthood for their children. Members of A 1 agree to sacrifice four years of resources to retain their own progeny in childhood. This has opportunity costs measured by both time and lost savings. This reduces future living standards of Generation One. Generation Two expects expanded future opportunities from higher C and H with an understanding that E (future family resources) will be lower. In isolation, this is a genera tional transfer of resources; time earning wages from A 1 given to A 2 via payments to universities. 3. Trend Two: privatization of higher education Mainstream US Economics and Economists long assumed zero externalities. Markets are perfectly and instantly adjusting, spontaneously determinate, equilibrium generators. Unique, determinate, optimal equilibria assume no externalities and are themselves dependent on the absence of externalities. Tautologies aside, the grand movement of university education as a public good started in the 19 th Century with the Morrill Act of 1862; and starting in the 1980s, state legislators have eroded via budget committees. As late as 1980, universities received more than 80% of their total funds from government agencies. Most funds came through direct payments for each student attending, research grant support, or specific program support for “high need” areas of study. They consisted of funds, land, buildings, and even veteran supports for former military personnel. By 2010, a fundamental philosophical dilemma arose. Why are non-students and other members of Generation One required to pay for someone Proceedings of 3rd European Business Research Conference 4 - 5 September 2014, Sheraton Roma, Rome, Italy, ISBN: 978-1-922069-59-7 else‟s H? If externalities do not exist, by what purpose can such support be justified? Government began to redefine higher education from: "This bill proposes to establish at least one college in every State upon a sure and perpetual foundation, accessible to all, but especially to the sons of toil,…” Justin Smith Morrill 1962 [Parker 1924] To: “The Republican vision for expa nding access to higher education has led to two major advances, Education Savings Accounts and Section 529 accounts, by which millions of families now save for college.” Defending Our Nation - 2008 Republican Party National Platform. Many parents lament the highest cost of higher education, but per student served, costs are very much in line with the wider inflation rate since the 1970s. State and federal funds represent less than 50% of university revenue streams [State Higher Education Executive Officers Association 2014]. This decline shifted costs. Private grants have increased, but private costs have nearly tripled as a percentage of the university revenue stream. This man-made storm has increased the relative value of human capital accumulation at the expense of those trying to purchase it. Essentially, by reducing the funding stream, regulators were shifting resources in two fundamental ways. The first transfers the costs of universities away from the wider population thereby increasing their range of choices within their opportunity sets. Inversely, this serves to reduce the range of Proceedings of 3rd European Business Research Conference 4 - 5 September 2014, Sheraton Roma, Rome, Italy, ISBN: 978-1-922069-59-7 choices available to those members of A (both the older and younger generational members). The second is to inflate the perceived market prices of a university education. As market prices are the result of the valuation process, education has more value. This widens the range of choices available to sellers. The US has begun a process of socializing the risks of illness with national insurance schemes under the Affordable Care Act. Military risks are socialized with national defense, and the risks of old age and disability with a national pension system. National education funding socialized the risk of structural changes to the economy. Such structural change results in endemic unemployment with little hope of reemployment until new skills sets of developed. As no one knows ahead of time if they will: get sick, need military protection, become too old or disabled to work, or become technologically redundant, we were all participants in the allocation of such programs. For university funding, this also socialized the need for basic research (a traditional function of public universities). Through their power to change the legal environment in which agents operate, the government has redefined higher education as a private good, consistent with the hegemonic worldview of efficient markets operating best with minimal government participation and devoid of externalities. Externalities‟ existential crisis is still in play from a policy perspective. While every primary and secondary school is legally required to educate all young people to be college ready regardless of their socioeconomic or physical condition, we continue defunding public higher education. Proceedings of 3rd European Business Research Conference 4 - 5 September 2014, Sheraton Roma, Rome, Italy, ISBN: 978-1-922069-59-7 As a result, we are reducing the opportunity set of A by increasing the market value of an asset set not possessed by members of A. essentially a zero-sum-game. The widening of other agents is This makes the shift appear even greater for those paying for the resource. By privatizing, private agents have begun to make both the indirect sacrifice of time (waiting for member of A 2 to mature), but now A 1 and A2 are borrowing against future earnings. In a bizarre irony, to close the funding gap, these members of A are borrowing from the very government that shifted the cost burden. They repay these loans with interest rates presently more than twelve times the level of those paid by profit making entities borrowing from government. To dissuade members of A 2 from defaulting, rules were further changed to make it illegal for A 2 to do so. Not unemployment, bankruptcy, nor even death can easily reduce the interest or principal repayment. Debts are transferred to member of A 1 or extracted in the transfer of estate from A 2 to A3. This is one of the most profitable government activities outside direct taxation and represents tens of billions in annual interest payments. The size of this private debt is staggering. Already over $1.1Trillion, an unknown sum is owed to private entities for personal loans used for indirect costs (families borrowing to pay for exigencies while supporting an immature adult-child in university). To repay a trillion will take time. The latest program to “ease” the burden stretches payments by converti ng from an amortization schedule to a 25-year plan costing 10% of Gross Household Income. For a 23-year-old graduate, they will pay 10% of their Proceedings of 3rd European Business Research Conference 4 - 5 September 2014, Sheraton Roma, Rome, Italy, ISBN: 978-1-922069-59-7 Gross Income until age 48 or until the debt plus interest is repaid. With nearly 10% of loan balances exceeding $100,000, participants are more likely to age-out rather than pay-off their debt. Their indentured servitude is due to the greater than 6% interest accumulating faster than their gross earnings can pay it down. Such plans represent less-than-interest-only plans with a growing balance on loans as low as $50,000 for many graduates in common fields of study. This represents nearly one -third of all current and recent graduates with employment. Factor in the additional 20% without full-time employment and the 48% that fail to complete their university programs and the odds of repayment instead of aging-out are surprisingly low. 4. Trend Three: the market is gross, but living is net and falling. Below is a table showing a trend path explained in more detail in other research by this author [Johnson 2012 and 2014]. In summary, we have seen a remarkable downward trend in the proportion of household gross income retained as spendable earnings. This trend is troubling at many levels. Households are encouraged to purchase housing and absorb other debt-laden purchases based on gross earnings. Regional and local taxation, payroll taxes, health insurance costs, and pension costs have increased from less than 1% to nearly 10% of gross income by 1975. Since 1975, this upward trend in pre-discretionary costs have accelerated upward with the transfer of pension and health care costs onto individuals and a shift in government funding of programs away from federal and onto local levels of government. Prior to any middle-income household making periodic choices with their income, they lose approximately 80% of gross income. Proceedings of 3rd European Business Research Conference 4 - 5 September 2014, Sheraton Roma, Rome, Italy, ISBN: 978-1-922069-59-7 CATEGORY YEAR 1935 1950 1975 2013 100% 100% 100% 100% Federal Income Tax 4% <10% 14% 12% Federal Payroll Tax 0% 1.5% 5.85% 7.65% State Taxes <1% 1% <3% >6% Health Insurance 0% 0% <0.5% >10% Pension Premium 0% 0% 0% 15% 95% 88% 77% 47% 28% Mortgage Held 28% 28% 28% 28% Communications 0% <1% <1% >5% 67% 60% 48% 16% Gross Income Net Income Spendable Earnings Obviously, once a household is enrolled in a 25 -year repayment plan to repay their educational debt, it would be highly improbable that they could afford to maintain typical lifestyle expectations; health insurance, retirement savings, housing, and tax obligations; and this is before food, clothing or children of their own. This means delaying one (or more) of these expenses until age 48, deferring what was once an early act of independence (home ownership), to a mid-life choice. Financial institutions, government agencies, and educational institutions overwhelmingly make use of gross income to determine credit-worthiness, public Proceedings of 3rd European Business Research Conference 4 - 5 September 2014, Sheraton Roma, Rome, Italy, ISBN: 978-1-922069-59-7 obligations, and sliding scale tuition prices. Uni versities use their monopoly position to engage in price discrimination based on individual household gross assets. This process is codified through the use of a national information data collection system for prospective university students called FAFSA (Free Application for Federal Student Aid). On it, students and their families reveal all personal financial assets, income tax return file access, and are then quoted prices by each institution following this great reveal. While markets frequently make use of household gross income to define economic class, housing affordability, tax obligations, and health insurance costs, households must live on the remaining net income. 5. Conclusions Combining these three institutional changes to the socio-legal-economic nexus in which agents operate results in a very different outcome than a simple PPF curve is able to indicate. The non-existence of externalities justified the elimination of socially (employer groups) funded pensions. Similarly, their absence is being used as justification for reversing recent laws designed to socialize the risks of illness (US Affordable Care Act). Further efforts to reverse old age and survivor insurance programs are underway in an ongoing discussion of privatizing social pension accounts. Essentially: Proceedings of 3rd European Business Research Conference 4 - 5 September 2014, Sheraton Roma, Rome, Italy, ISBN: 978-1-922069-59-7 A1‟s opportunity set is reduced by the implicit and explicit costs of supporting the younger generation in their household for at least four additional years. A2‟s opportunity set is reduced by the investment of time in university education and the costs of participation. A‟s opportunity sets are reduced by the transition from a public good model to a private good delivery model for higher education as cost burdens are shifted. A‟s opportunity sets are falling as privatization has occurred in the last 30 years across other areas of risk. A2, in addition to the typical lifestyle expectations (housing, pension savings, health insurance, and taxes), are negotiating for a transfer of resources. They are buying relatively higher valued human capital investments with devalued assets. This makes entry into the human capital market even more expensive. To address this increase in educational costs, households are contracting to sacrifice 10% of gross earnings out of a proportionally small remainder. While highly efficient in the allocation process, markets fail to identify the underlying conditions in which they operate. This interconnection in taxes, housing, pension, health care, and educational costs makes it difficult to imagine that other nations would want to emulate the US delivery model. Nations that are transitioning toward a private good model for higher education are finding similar results. Young adults with relatively few resources are confronting ever-increasing barriers to entry in the education market. The distortion occurs as both the relative valuation of the products Proceedings of 3rd European Business Research Conference 4 - 5 September 2014, Sheraton Roma, Rome, Italy, ISBN: 978-1-922069-59-7 changes the effective opportunity sets of participants and as private agents cover the costs of production. These three shifts represent considerable emmizerization of a large swath of the population and delays their financial adulthood by upwards of 25 years. From a life cycle perspective, we are truncating the accumulation stage in the lives of millions of people. 6. References Commons, John R. 1924, 1995 Legal Foundations of Capitalism, New Jersey: Transaction Publishers. Flaim, Paul O. 1982 “The spendable earnings series: has it outlived its usefulness?” Monthly Labor Review (January 1982) p.3-9. Flow of Funds Reports 1970-2012 New York: Federal Reserve Bank of New York. Handbook of Labor Statistics 1970-2000 Washington DC: Bureau of Labor Statistics. Johnson, Kirk Douglas “Recovering from the Housing Bubble; when social traditions transmogrify into institutional rules” Papers and Proceedings of EAEPE Annual Meetings Krakow 2012. Johnson, Kirk Douglas “Traditions, Rules and Social Conditions; when mutually exclusive institutional structures meet” Papers and Proceedings of GBI Paris Meetings 2014. Mazo, Judith, Anna Rappaport, and Sylvester Schieber 1994 Providing Health Care Benefits in Retirement, Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press. Nyce, Steven and Sylvester Schieber 2010 “Health Care Inflation” Milken Institute Review (Q2, 2010) p.46-57. Obama, Barack “Remarks at an America‟s Promise Alliance Education Event” accessed July 28, 2014 at http://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/pkg/DCPD201000135/pdf/DCPD-201000135.pdf. Parker, William Belmont, The Life and Public Services of Justin Smith Morrill, 1924, page 52. Paulson, Amanda, “No Child Left Behind Embraces College and Career-Readiness, accessed July 13, 2014 at: Proceedings of 3rd European Business Research Conference 4 - 5 September 2014, Sheraton Roma, Rome, Italy, ISBN: 978-1-922069-59-7 http://www.csmonitor.com/USA/Society/2010/0323/No-Child-Left-Behindembraces-college-and-career-readiness. Republican Party 2008 Defending Our Nation National Platform. Samuels, Warren J. 2011 Erasing the Invisible Hand: Essays on an Elusive and Misused Concept in Economics, with the assistance of Marianne F. Johnson and William H. Perry, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Samuels, Warren J. 1992 Essays on the Economic Role of Government, vol. 1, Fundamentals, London and New York: MacMillan and New York University Press. Schieber, Sylvester J. 2012 The Predictable Surprise: the Unraveling of the U.S. Retirement System, New York: Oxford University Press, USA. State Higher Education Executive Officers Association, State Higher Education Funding FY2013 accessed July 13, 2014 at http://www.cbpp.org/cms/?fa=view&id=4135 State Individual Tax Rates, 2000-2011, TaxFoundation.org accessed http://taxfoundation.org/article/state-individual-income-tax-rates-2000-2012. at Statistical Abstract of the United States 1950-2013 Washington DC: United States Census Bureau. Strong, Jay V. 1951 Employee Benefit Plans in Operation, Washington DC: Bureau of National Affairs. US Federal Individual Income Tax Rates History 1913-2013, TaxFoundation.org, accessed at http://taxfoundation.ord/article/us-federal-individual-income-taxrates-history-1913-2013-nominal-and-inflation-adjusted-brackets.