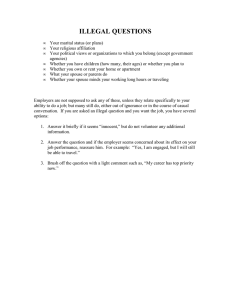

Extramarital Relationships and the Theoretical Rationales for the Joint Property Rules – A

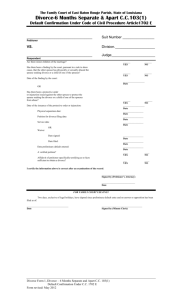

advertisement