Social Persuasion in Human-Agent Interaction

advertisement

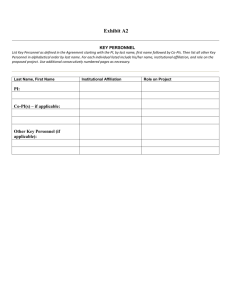

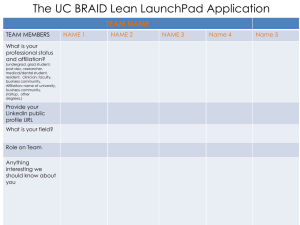

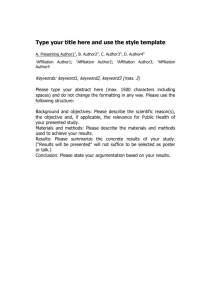

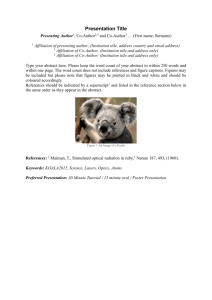

Social Persuasion in Human-Agent Interaction Yasuhiro Katagiri Advanced Telecommunications Research Institute International Toru Takahashi ATR Media Integration & Communications Research Labs. Yugo Takeuchi Shizuoka University Abstract Social persuasion abounds in human-human interactions. Our attitudes and behaviors are invariably influenced by attitudes and behaviors of other people as well as our social roles/relationships toward them. We discuss, in this paper, the design of interface agents that considers the social aspects in human-agent interaction. The underlying hypothesis of the design is that human social behaviors toward interface agents are on a par with those toward humans. We report on two preliminary experimental studies focused on the nature and the effectiveness of social persuasion in human-computer interaction environments. We argue that social factors, such as affiliation, authority and conformity, need to be taken into account in interface agent design, as they can have effective and persuasive power in human-agent interaction. 1 Introduction Interface agents that mediate between humans and computers are expected to play an increasingly important role in “human-oriented” information systems. The research in intelligent interface agent technologies have been aiming to develop an electronic servant that serve to help people cope with information overload created by the “machine-oriented” information technologies, by providing an effective means for search, extraction and filtering of information [Maes, 1994; Good et. al., 1999]. With their various personification features, interface agents are expected to alleviate the labor and mental burden that people have been experiencing in complicated tasks of working with computers. With the recent interest in anthromorphized agents or embodied agents, an emphasis is also placed on emotional and relational aspects of interaction with interface agents [Nagao and Takeuchi, 1994; Ball et. al., 1997; Laurel, 1990; Cassell, 2000; Cassell and Bickmore, 2000]. Multi-modal information channels, e.g., the capabilities of exchanging information via voice, gestures, gaze and facial expressions in addition to language, have the potential of providing us with natural means to foster affection, pleasure and trust as well as to exchange information with computers. Reeves & Nass [Reeves and Nass, 1996] have convincingly demonstrated that people’s spontaneous responses to computers follow exactly the principles of human-human social interactions and this social nature of human behaviors toward computers are universal and consistent. Takeuchi&Katagiri [1999] examined human responses toward animated computer agents and suggested the possibility for system designers to affect users’ behaviors by inducing human social interpersonal reactions toward interface agents. We report, in this paper, on two experiments that focused on the potentials of social persuasive functions of interface agents. The first experiment investigated the possibilities and effects of creating affiliative relationships between humans and interface agents. The second experiment examined the possibilities and effects of displaying inter-personal relationships through inter-agent interactions. Though both experiments produced only preliminary results, it seems they indicate that the social dynamics in interactions involving interface agents work as effectively and persuasively as in human interactions. 2 Elements of Social Persuasion 2.1 Affiliation Need in Human-Agent Interaction There is an essential need for humans to establish and maintain affinitive relationships with others. This need is called the affiliation need. The affiliation need is important when we consider human relations or group formation. People who want to establish and maintain a friendly relationship with another person are apt to follow or sympathize with this person [Schachter, 1959]. If such social relationships based on affiliation need are established between users and interface agents, we expect that the user will try to establish and maintain a relationship with the agents. To induce affiliation needs in users, we note the following two types of interpersonal attraction of interface agents: Appearance-based attraction: The interpersonal attraction we feel based on the outward appearances (figures, vocal qualities, etc.) and the internal traits (character, orientation, etc.) of the interface agents Capability-based attraction: The personal attraction we feel based on profits and benefits by interacting with interface agents Establishing and Maintaining Affinitive Relationships The appearance of a person has a great effect on first impressions. The appearance-based interpersonal attraction of an agent will also have such an effect on the user’s first impression of the agent. This will induce the user’s affiliation need in the first encounter. Therefore, the appearance of the interface agent is important in establishing the affinitive relationship between the user and the agent. The strength of the affinitive relationships can vary. Cooperative or agreeable behaviors enhance the relationship, whereas uncooperative or disagreeable behaviors damage it. When people find that their partner can provide benefit for them, they feel capability-based attraction toward their partner and try to enhance the relationship by increasing their affiliation needs. When their partner shows negative attitudes toward them, they might even assume that the partner has lessened the affiliation need toward them and try to compensate for this to maintain the affinitive relationship. They will then feel an enhanced affiliation need toward the partner and try to recover their former state of relationship by trying to sympathize with the partner and respond positively to the partner’s requests [Cialdini and Kenrick, 1976]. Human orientation of establishing and maintaining affinitive relationships can be adapted to interactions with interface agents. It should be possible to design the behavior of an agent-interfaced system that implements life-like social interaction based on users’ affiliation needs. 2.2 Authority and Conformity in Inter-Agent Interaction Interface agents can lead us towards making accurate inferences about how an agent is likely to think, decide, and act on the basis of its external traits such as its appearance, voice, and communication style. Even though multiple interface agents are simultaneously driven by the same program on a computer, people attribute a specific identity to each agent [Takeuchi and Katagiri, 2000]. This human response towards agents suggests that people would regard agent-agent (interagent) interaction (such as conversations, social acts, or nonverbal communications) as having the same social dynamics as human-human interaction. Virtual theatrical inter-agent interaction can be accepted as a natural social activity similar to that of humans. Expertise and Authority Authority is inherent in the actions exercised by those who are experts and have special knowledge and skills. People, therefore, frequently prefer to believe news sources that have higher expertise1 rather than others [Reeves and Nass, 1996] even though the news itself is completely the same. This human response is entirely the consequence of people accepting authority accompanied by expertise as an attribution of information. Furthermore, in situations where people need special knowledge or skills, the person who is respectfully treated with reverence seems to have higher expertise. 1 e.g. CNN, HNN, SNC, and RNN Figure 1: Information Kiosk and PalmGuide Conformity The attitudes and behaviors of other people or groups frequently change our own attitudes and behaviors. Conforming one’s attitude and behavior to a person or group who can exercise authority or to an influential power, is a sensible strategy for receiving further benefits as a basic social skill in general [Asch, 1951]. In the public arena, moreover, we prefer to choose a strategy to conform our interpersonal behavior style with other people in order to avoid social friction. These strategies are effective in social life. Persons or groups have the competence to change the actions of others based on expectations, and this is power accompanied with authority according to its influence [Tawney, 1931]. 3 Experience from Human-Agent Interactions 3.1 Exhibition Guidance System We first studied the affiliation need based social interaction between humans and agents by incorporating a set of interface agents into the Exhibition Guidance System C-MAP developed in ATR. The C-MAP (Context-aware Mobile Assistant Project) Exhibition Guidance [Sumi, 1998] features a personal mobile assistant that provides visitors touring exhibitions with information based on user contexts. The user of the system carries a hand-held guidance system called PalmGuide while touring an exhibition. PalmGuide maintains user contexts such as user’s name and affiliation, temporal and spatial situations of the exhibition, history of the tour, and personal interests (Figure 1). A personal guide agent runs on the user’s PalmGuide and provides tour navigation information such as introduction of exhibit articles and recommendations of what to visit next. This recommendation is made from the result of calculating the user’s interest by using information of other users’ contexts. At exhibitions using this C-MAP system, information terminals called Information Kiosks are installed at each ex- Figure 2: Appearance of the Agents hibit. Information Kiosks usually provide information about the overall exhibition. When a user with a PalmGuide comes to an Information Kiosk, the user can connect her PalmGuide to the Information Kiosk by infrared communication. Then, the user’s guide agent migrates to and personalizes this Information Kiosk. The guide agent on the Information Kiosk gives interactive guidance of the particular exhibit with animated motion and synthesized voice. After the user finishes obtaining information with the agent’s guidance, the agent returns to the original PalmGuide and goes to the next exhibit with the agent’s user. 3.2 Interpersonal Attraction To solicit user affiliation needs toward interface agents, we have designed the following two aspects of interpersonal attraction: Appearance-based attraction Each user selects the appearance of her personal interface agent. She can freely choose her favorite from a selection of nine prepared agents (Fig. 2). Capability-based attraction The interface agent has the capability of providing its user with integrated information based on her context, as the agent comes along with its user and constantly revises her personal data and interests from her tour history. 3.3 Observational Analysis We analyzed the affiliation need based interaction by examining users’ behaviors toward recommendations made by their personal guide agents. Setting We installed and ran the C-MAP Exhibition Guidance System at ATR Open House, and observed the behaviors of the visitors who used the guide agent system. The visitors received their PalmGuides and were allowed to freely roam around the exhibits. A total of 21 Information Kiosks were installed at the exhibit booths. We compared the observed users’ tour histories with the recommended exhibits. We designed the behaviors of the guide agents as follows: Figure 3: Acceptance rate of recommendation (Means/SE) 1. Until the fourth access to an Information Kiosk, the guide agent returns to the PalmGuide when the access ends and comes along with the user to the next exhibit. 2. At the end of the fourth access, after giving the user a recommendation for the next exhibit, the agent tells the user that it will go ahead directly to the recommended exhibit and wait for the user there, and disappears from the Information Kiosk. Depending on the user’s following behaviors, two types of situations follow at the fifth access to an Information Kiosk. A. The user accesses the recommended exhibit. The agent thanks the user for her trust in the agent’s recommendation. B. The user accesses an exhibit different from the recommended one. The agent complains that the user doesn’t follow the agent’s recommendation. In either case, we expect that the agent’s reaction induces its user’s affiliation need and has an effect on the user’s subsequent behaviors. In situations of type A, we expect her affiliation need toward the agent is enhanced because of its positive response. In situations of type B, we expect her affiliation need to also be enhanced, because the user worries that the social relationship with her agent would take a turn for the worse and hopes to recover the relationship. Results and Discussions We separated out two subject groups ( and ) out of the users of the system. consists of 22 users who accessed a Kiosk just four times and consists of 12 users who accessed a Kiosk more than five times. Psychological ratings based on questionnaire survey indicated that group rated higher than group of their attitudes toward both agents and interactions. Although statistically significant difference cannot be observed because of the small sample size, it is consistent with the view that the feedback of the guide agent in the fifth access is influential in setting user attitudes. Figure 3 compares the acceptance rates of recommendations. The leftmost bar shows the mean acceptance accep tance rate for . Right two bars are rates for before and after each user obtained feedback from her agent based on the user’s response to the agent’s recommendation in the fifth access. Left two bars show a similar behavior tendency, but the rightmost bar shows a higher rate than others. The figure indicates that people tend to behave differently toward the guide agents’ recommendations before and after the fifth access, when the agents simply went ahead and waited for their users at the recommended Information Kiosk. The data of the observational exhibited analysis only a statistical tendency ( ), mostly because we haven’t been able to get a large enough number of users suitable for analysis. Nevertheless, we believe this difference in behaviors is important as it reflects the strength and effectiveness of the users’ affiliation needs toward guide agents in selecting behaviors. Guide agents complained to 11 users out of 12 because these 11 users didn’t access the recommended exhibit’s kiosk directly after the end of their fourth access. Therefore, by comparing the data, we can conclude that the guide agents’ action enhanced the users’ affiliation needs toward the agent. The users hope and try to recover the affinitive relationship with the agent. Namely, we can explain the changes in user behaviors as being controlled by the enhancement of affiliation needs, which are effected by social interactions between the users and their agents. 4 Experience from Inter-Agent Interactions 4.1 Interface Agents in Web-based Instruction In order to further examine and verify the social nature of human-agent interaction, we expand the scope of interaction to include agent-agent as well as human-agent interaction. We developed a prototype system of Web-based multi-agent instruction to elucidate the effects of social factors such as authority and conformity in human-agent interactions and to investigate methodologies to incorporate those factors to better the design of instructional systems. A Multi-Agent Instruction Scheme In the traditional Web world, the authors of the Web pages have an inventory of visual (and auditory) design parameters, such as choice of color, sound, layout and style, to control the salience of a particular page and to preserve coherence across several pages. They manipulate those parameters to make their Web contents more comprehensible and persuasive. Animated interface agents provide them with a huge possibilities to further extend the expressiveness of Web contents. We started exploring this extended expressiveness provided by interface agents by looking at the following simple multi-agent instruction scheme. 1. Each user is associated with an agent called the Conductor Agent (CA). The CA always accompanies the user and guides her through the Web pages. 2. Each set of Web pages for a meaningful unit of Web contents is associated with an agent called the Expert Agent (EA). The EA always resides in its content pages and gives descriptions of their information contents whenever a user visits its pages. 3. One of the tasks of the CA is to mediate the interactions between the user and various EAs. The CA introduces Figure 4: A Multi-Agent instruction scheme for Web contents. the user to an EA upon entering its pages. These interagent interactions are theatrically demonstrated on the Web pages in front of the user (Figure 4). We assign the jobs of CA and EAs to the character agents shown in Figure 2 The scheme above was intended to focus on the following two tendencies of human social responses: Expertise People prefer to accept information from sources assumed to have higher expertise. Conformity People prefer to choose a strategy to conform to the interpersonal behavioral style of other people with supposed equal social positions to themselves. The guiding intuition was that the style of interaction between a CA and an EA, together with the user’s tendency for conformity, influences the user’s attribution of expertise to the EA, which then contributes to the user’s assessment of authority in the content of the pages the EA is in. Polite interaction The CA politely interacts with an EA. By conformity to the interaction style of the CA and the EA, the user recognizes the authority of the Web page contents corresponding to the EA. Casual interaction The CA casually interacts with an EA. By conformity to the interaction style of the CA and the EA, the user do not attribute authority to the Web page contents corresponding to the EA. In order to theatrically realize the two interaction styles, we manipulated the CA’s behavior towards EAs as follows: Verbal expressions either deferential or colloquial to the EA. Modest or intimate attitude to the EA. Distinguished verbal expressions and attitudes directed towards the participant. 4.2 Experimental Analysis Multi-Agent Instruction for Cooking A prototype system was developed in the cooking instruction domain to help the intended user accurately understand the contents and adequately carry out the cooking steps instructed in the contents of Web pages. Social inter-agent interactions in the two contrasting styles were theatrically demonstrated in the system to see if they make any changes in user attitudes and performance. Tips (1) (2) (3) (4) (5) (6) % % % % % % % % % % Participants ! % % "# % % % "$ % % Table 1: Knowledge about cooking tips. (a) Inter-agent interaction in introduction phase (b) Instruction giving phase Figure 6: Custard puddings produced in the Polite condition (left) and in the Casual condition (right). Figure 5: Interactions in a multi-agent cooking instruction. We prepared a series of Web pages for a custard pudding cooking recipe. The learners can actually make custard puddings as they go through those pages and watch social interagent interactions that take place in the pages. Four pages were created for each of the cooking steps, and an EA was assigned to each page, as an expert of the corresponding cooking step. A CA accompanies the user as she goes through the four steps. When the user enters a page to initiate a new cooking step, the CA introduces her to the EA before the EA starts the instruction. The user is required to follow the instruction, which is given both in vocal and document forms, to successfully complete the step. Figure 5 shows the introduction and the instruction phases in a cooking instruction step. Method We conducted an experiment to explore whether the behavior and the attitudes of people are affected by social inter-agent interaction in Web pages. The inter-agent interactions took place in the form of greetings and requests between CAs and EAs. At the start of each cooking step, the CA vocally speaks to the EA in either of the following two interaction styles: Polite condition The CA politely introduces the user to the EA and asks him in a modest manner to give instructions for cooking to the user. Casual condition The CA casually introduces the user to the EA and asks him in a colloquial style to give instructions for cooking to the user. The participants of the experiment were instructed to cook a custard pudding by going through the steps in the Web instructions. A questionnaire test was performed after the ses- sion to see if participants correctly acquired the cooking tips given in the instructions. Performance was also assessed from the actual cooking outcomes. Three participants were assigned to the Polite condition and two participants to the Casual condition. The five participants were not proficient in baking cakes, cookies, or pastries such as custard pudding, although they could use computers well and stated that they usually browse various Web pages. Predictions One’s social authority is characterized from how the surrounding people treat her as well as her appearance and behaviors. We assume that, in our experiment, people recognize the EA’s authority and conform to the CA’s treatment of the EA. The results can therefore be predicted as follows: (P1) The participants assigned to the Polite condition will score higher than those assigned to the Casual condition in a test of knowledge in making custard puddings. (P2) A better cooking performance will be achieved by the participants under the Polite condition than those under the Casual condition. Results and Discussions Table 1 shows the number of cooking tips given by the EAs and also described in the corresponding Web pages which were correctly answered in the post cooking questionnaire test. Table 1 shows that three participants ( &$'()&+* ) assigned to the Polite condition acquired more tips correctly than the two participants ( , ' and ,.- ) assigned to the Casual condition. The exemplary cooking outcomes in the Polite and the Casual conditions are shown in Figure 6. There is an obvious difference in the performance between the two conditions. The surface of the left pudding is smooth and visually goodlooking / compared to the right pudding. There were also obvious differences in taste between them. These assessments seem to indicate that the performance of achieving the given task was influenced by the conditions of whether CA respectfully interacted with EAs. Both the acquired cooking knowledge result and the cooking performance result confirmed our predictions P1 and P2. The people in the Polite condition achieved better than the people in the Casual condition both in terms of knowledge and performance. These results support our hypothesis that people recognize expertise and authority in inter-agent interactions between the CA and the EAs, and adjust their attitudes and behaviors in conformance to them. 5 Conclusions We reported on two preliminary experiments focusing on the persuasive potentials of interface agents. The results of both of the experiments appear to suggest that social interaction with and between interface agents have the persuasive power to influence people’s attitudes and behaviors, though we need more participants in experiments to get to statistically clear evidences. The interface agent, designed to induce users’ affiliation needs, did actually change user behaviors in the first experiment. Inter-personal relationship, e.g., authority, displayed by one agent toward another did change social attitudes and behaviors of people in the second experiment. These findings have significant importance for HumanComputer interface design. Current computer interfaces frequently require us to follow explicit messages produced by computers, e.g., “Insert a floppy disk into FDD,” “Drop these files into trash box,” or “Click this button to confirm,” to which users are forced to comply. Users might feel stressed in this style of system operation, as they are always obliged to obey the messages. The affiliation need of a user toward her computer might be effectively applied to maintain intimate relationships. Once a reciprocal relationship between human and computer is established, people strive to keep their intimate relationship. When computers blame users for their insincerity, negligence, or other unsocial behaviors toward computers, users would tend to obey computers’ requirements to compensate for the damages to their intimate relationships, with positive feelings of cooperating with the computer. People are also sensitive to social power such as expertise and authority, and they would adjust their behaviors accordingly, even if the power is merely theatrically acted out among interface agents. Interface designers must be aware of these potentials to enhance the quality as well as the efficiency of human-computer interactions. Acknowledgments We are grateful to Dr. Yasuyuki Sumi for cooperating with us in using the C-MAP Exhibition Guidance System. We also sincerely thank Ms. Keiko Nakao who made a great effort in designing attractive appearances of the agents. References [Asch, 1951] S. E. Asch. Effects of group pressure upon the modification and distortion of judgments. In H. Guetzkow, editor, Groups, leadership, and men. Carnegie Press, 1951. [Ball et. al., 1997] G. Ball et. al. Lifelike computer characters: the Persona project at Microsoft. In M. Bradshaw, editor, Software Agents, pages 191–222. 1997. [Cassell and Bickmore, 2000] J. Cassell and T. Bickmore. External manifestations of trustworthiness in the interface. Communications of the ACM, 43(12):50–56, 2000. [Cassell, 2000] Justine Cassell. More than just another pretty face: embodied conversational interface agents. Communications of the ACM, 43(4):70–78, 2000. [Cialdini and Kenrick, 1976] R. B. Cialdini and D. T. Kenrick. Altruism as hedonism: A social development perspective on the relationship of negative mood state and helping. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 34:907–914, 1976. [Good et. al., 1999] N. Good et. al. Combining collaborative filtering with personal agents for better recommendations. In Proceedings of AAAI’99, pages 439–446, 1999. [Laurel, 1990] B. Laurel. Interface agents: metaphors with characters. In B. Laurel, editor, The art of humancomputer interface design. Apple Computer, 1990. [Maes, 1994] P. Maes. Agent that reduce work and information overload. Communication of the ACM, 37(7):31–40, 1994. [Nagao and Takeuchi, 1994] K. Nagao and A. Takeuchi. Social interaction: Multimodal conversation with social agents. In Proceedings of AAAI’94, pages 22–28, 1994. [Reeves and Nass, 1996] Byron Reeves and Clifford Nass. The Media Equation. Cambridge University Press, 1996. [Schachter, 1959] S. Schachter. The psychology of affiliation. Stanford University Press, 1959. [Sumi, 1998] Y. Sumi. C-MAP: Building a context-aware mobile assistant for exhibition tours. In T. Ishida, editor, Community computing and support systems, pages 137– 154. Springer, 1998. [Takeuchi and Katagiri, 1999] Yugo Takeuchi and Yasuhiro Katagiri. Social character design for animated agents. In Proceedings of RO-MAN99, pages 53–58, 1999. [Takeuchi and Katagiri, 2000] Yugo Takeuchi and Yasuhiro Katagiri. Identity attribution in social interaction with agents (in Japaese). Correspondences on Human Interface, 2(3):91–98, 2000. [Tawney, 1931] R. H. Tawney. Equality. Harcourt Brace, 1931.