Research Journal of Applied Sciences, Engineering and Technology 4(6): 675-685,... ISSN: 2040-7467 © Maxwell Scientific Organization, 2012

advertisement

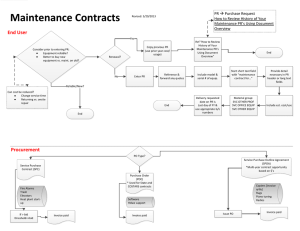

Research Journal of Applied Sciences, Engineering and Technology 4(6): 675-685, 2012 ISSN: 2040-7467 © Maxwell Scientific Organization, 2012 Submitted: December 16, 2012 Accepted: January 08, 2012 Published: March 15, 2012 Statistical Analysis of Shunt-FACTS Devices Impact on Power Flow Control Mohammad Karimi, Payam Farhadi, Mohammad Bagher Ahmadi, Tina Sojoudi and Davood Mostafa Young Researchers Club, Parsabad Moghan Branch, Islamic Azad University, Parsabad Moghan, Iran Abstract: In this study, impact of Static VAr Compensator (SVC) on power flow control is studied by statistical indices. For this purpose, several conventional branches of SVC are introduced and their impacts are discuses on active and reactive powers flow control on power systems. Peak and least values used as decision criteria. To compare and discuss the capability of compared SVCs, two statistical indices are used; i.e. Absolute Percentage Error (APE) and Symmetric Mean Absolute Percentage Error (SMAPE). These indices help to result in analysis and extract novel aspect of behavior of SVCs. Simulations have been carried out in MATLAB/SIMULINK environment. In this study, first a general review on lectures about SVC has been done which has four parts; i.e. design, placement, application and modeling, respectively. Then, the most useful branch is chosen. Key words: Power flow control, Shunt-FACTS devices, statistical indices, SVC INTRODUCTION Simple structure and many capabilities of SVC has led to composite new structure with other devices; e.g. AVR for voltage control (Vachirasricirikul et al., 2010), PSS for damping multi electromechanical modes in multimachine systems (Bian et al., 2011), and to increase power system stability (Abido and Abdel-Magid, 2003). To damp rotor angle oscillations and improve the stability, Karpagam et al. (2010) suggested an improved FLC for SVC. Main contribution of proposed FLC is oscillations damping with faster rate and optimal utilization of the SVC in system-overloading conditions. Sun et al. (2011) have designed a SVC based on H4 controller to damp coefficient uncertainty by modifying adaptive backstepping sliding mode control method and Lyapunov methods. Simulations have been done by MATLAB software on SMIB case system. A novel approach based on interval systems theory and Kharitonov’s Theorem was proposes by Robak (2009), to improve electromechanical oscillations damping using SVC. Proposed approach resulted in facilitating the design of a low-order, fixed-parameter and robust controller. Venayagamoorthy and Sandhya (2008) have designed a DFN controller based on wide-area measurements to improve damping characteristics of power system. The main advantage of the DFN controller is its simple structure with less development time and hardware requirements for real-time implementation. Finding optimal SVC location resuled in better performance in power system. Benabid et al. (2009) have used NSPSO to find optimal placement of SVC and TCSC. The proposed technique was tested on IEEE (1994) 30-bus and realistic Algerian 114-bus power The SVC is basically a shunt-connected static VAr generator/load its output is adjusted by exchange capacitive or inductive current, so as to maintain or control specific power system variables; typically, the controlled variable is the SVC busbar voltage. However, by growing use of the SVC, the coordination design problem of multiple SVC controllers in joint operation should be considered in practical power systems (Zou et al., 2005). Many lectures have studied SVC in different aspects. The lectures are classified in four categories; i.e. designing applications, optimal placement and analysis. Changes and improvements have been proposed to optimal performance of SVC. Then, this part of review consists of three subparts: structure modification and composition as well as design controller. Mahanty (2010) has proposed MSVC for reactive power compensation to eliminate harmonic without filter. The modification is done by large value AC capacitor. The large value AC capacitor has obtained using two large value DC capacitors and power semiconductor devices. Modi et al. (2008) a MISO fuzzy neural network has been developed to evaluate voltage stability in presence of SVC. The proposed method has two stages; Kohonen self-organizing map and combination of different nonlinear membership functions proposed to reduce the input features and combination of different non-linear membership functions in first and second stage, respectively. Corresponding Author: Mohammad Karimi, Young Researchers Club, Parsabad Moghan Branch, Islamic Azad University, Parabad Moghan, Iran 675 Res. J. Appl. Sci. Eng. Technol., 4(6): 675-685, 2012 system and compared with PSO and NSGA. To enhance power system voltage stability in presence of SVC, Zhang et al. (2007) have used normal forms of diffeomorphism. In this study, to confirm ability of proposed approach, steady-state voltage stability index and the time domain simulation used as comparison criteria. In this research, New England 39-bus power system has used as test case. Farsangi et al. (2007), proposed first a technique to find optimal allocation of several SVCs based on their primary function and then the most proper input signal for supplementary controller is selected. Other criterion to seek optimal location of SVC is reactive power nodal price index. The proposed approach is tested on two practical Indian systems (Singh et al., 2007). The SVC has several capabilities which make it to be used for different targets; in wind system for voltage adjustment and as a phase compensator (Lahaçani et al., 2010; Yuan et al., 2010), voltage control capability (Li et al., 2009), reactive current control for load power factor correction (Kodsi et al., 2006), power system dynamic performance (Rahima et al., 2006). In several studies, diverse approaches for modeling and studying SVC have been suggested. Quintela et al. (2008) have presented three-phase model to analyze power system in presence of SVC. From the modeling, if a compensator does not deliver reactive power, its currents are always of a negative-sequence symmetrical current set. By comparing dynamic performance between SC and SVC, it can be verified that the SVC injects more reactive power and shows better performance during fault occurrences caused less voltage drop on its terminals, but during severe faults, SC performs better (Teleke et al., 2008). Impact of SVC and STATCOM on performance of distance relays are: errors in the impedance measurement, delayed response and incorrect phase selection, affecting relay response time and the phase selection of relay. To mitigate effect of SVC and STATCOM, there is three technique; modifying the logic in the existing channelaided schemes, modifying the input voltage and current at the relays to compensate for the effect of the current of the shunt-FACTS and detecting remote end breaker operation vice versa (Albasri et al., 2007). By using normal forms theory to analyze nonlinear interactions among multiple SVCs which leads to a better understanding of the system nonlinear behavior and can be employed to locate and design controllers, and can also be extended to accommodate more complex multi-machine power system and other FACTS devices (Zou et al., 2005). Main focus of this work is comparative study of several branches of SVC on power flow control. For this, behavior of several SVCs on active and reactive powers have been introduced. To compare how these six SVCs work, control parameters are used and two statistical indices have been introduced to analyze and discuss. (a) (b) Fig. 1: Basic SVCs: (a) TCR, (b) TSC Static VAr compensator (SVC): Reactors and capacitors controlled by thyristor, i.e., static VAr compensator, are one of FACTS devices. Primary purpose of using SVC is usually for rapid control of points with week voltage in network. This device has been used in transmission systems in order to improve the performance of the electric power system by providing voltage support; improving the power factor, transient stability and power system damping, reduce temporary over-voltages and control the reactive power flow (Zhou, 1993). One of the interesting issues about SVC is its diversity in structure which is outmost over the most common SVC explains. TCR: The basic element in this type is a reactor in series with an AC thyristor switch, shown in Fig. 1a. The fixed capacitor biases the reactive output of the compensator into the generating regime. The demand for reactive power is met by controlling the duration of the conducting interval in each half-period by gating pulses to the two oppositely poled thyristors (Montafio et al., 1993). TSC: In their simplest configuration, the TSCs are constituted by a capacitor bank where each capacitor may be connected to the system through a thyristor switch (Fig. 1b). Very often all the capacitors in the bank have the same size but, by suitably choosing different values for each capacitor, 2n different compensation levels could be provided. In the standard construction of a TSC a damping reactor is included to limit the rate of change of device current on switching and to dampen transients following the switching (Celli et al., 2000). TSC-TCR: In AC power distribution systems TSC-TCR are increasingly used in order to support the voltage, and improve the transient stability. In such a system, the number of switched "ON" capacitor banks is selected in order to generate reactive power in excess, while the reactors are controlled in order to absorb the difference 676 Res. J. Appl. Sci. Eng. Technol., 4(6): 675-685, 2012 Fig. 2: Structure of SVC with FC Fig. 3: SVC model using power flow PV bus between the reactive power generated by the capacitors and the reactive power must be injected in the mains (Thomas et al., 1994). In the active control range, current/susceptance and reactive power is varied to regulate voltage according to a slope characteristic. The slope value depends on the desired voltage regulation, the desired sharing of reactive power production between various sources, and other needs of the system. The slope is typically 14%. At the capacitive limit, the SVC becomes a shunt capacitor. At the inductive limit, the SVC becomes a shunt reactor (the current or reactive power may also be limited). With a conventional power flow program, the slope is represented by connecting the SVC to an auxiliary or phantom bus separated from the SVC high voltage bus by a reactance equal (on the SVC base) to the per unit slope. The auxiliary bus is then the PV bus. Figure 3 shows the concepts of modeling SVC slope using an auxiliary bus. The reactive power output of an SVC can be computed as: SVC with FC: By using TCR and TSC only capacitive or inductive compensation is possible, but in practice both types of compensation necessary. Therefore, for possibility to change inductive form to capacitive, fixed capacitor is connected to SVC structure (Fig. 2). C C C FC-TCR: FC-TCR type of static compensator is analyzed in detail. In this analysis a simplified circuit as well as an exact circuit of an FC-TCR is considered. The performances of the simplified and exact circuits are compared and the results are verified experimentally. FC-TSC-TCR: This SVC is composed of three branches; one, (i.e., TSC) is used to generate variable reactive power, and another, namely TCR, is for variable reactive power absorption and FC for fixed reactive power generation. FC-TSR-TCR: The FC-TSR-TCR system is modified by introducing TCRs. The TSR gives stepped variation in current and TCR gives smooth variation in current. Thus the range of control of reactive power can be increased by using TSR. The TSR system consists of three reactors and three IGBTs. Three different amplitudes of currents can be obtained by using three switches. The FC-TSR-TCR system is best suitable for dynamic loads (Vijayakumar et al., 2010). QSVC = Vt (Vt ! Vref) Xsl (1) Equation (1) is valid as long as the reactive power output of the SVC, QSVC is within limits set by Qind and Qcap; defined as (Preedavichit and Srivastava, 1998): Qind = BindV2ref (2) Qcap = BcapV2ref (3) Power analyze and basic structure of SVC and analyze the survey of such systems mathematically in (Quintela et al., 2008; Hammad, 1986) can be found, respectively. The model is completed by the algebraic equation expressing the reactive power injected at the SVC node; Fig. 4 (Zou et al., 2005): Modeling of SVC: The SVCs are often modeled as a conventional PV (generator) bus with reactive power limits. This results in large errors if the SVC is on limit, operating as a capacitor or reactor. If low voltage is the main concern, the SVC can be modeled as a FC-TCR type of SVC (PV bus with shunt capacitor). For example, for low voltage problems, a ±200 MVAr SVC can be represented as a 200 MVAr capacitor banks, and a PV bus with 400 MVAr inductive limits and zero capacitive limits; the capacitive limit is correctly represented but not the inductive limit. With a conventional power flow program, a SVC with susceptance regulator can be represented by a PQ (load) bus with voltage constraints. CALCULATING FIRING ANGELES OF THYRISTOR There are, mainly, three existing SVC models in load flow calculations, e.g., the generator-fixed susceptance model, the total susceptance model and the firing angle model. Calculating firing angle could be carried out in time or frequency domains. Assuming sinusoidal voltage source, calculating firing angle will be done with less complications. To calculate firing angles of TCR’s thyristors, equivalent circuit shown in Fig. 1 is transformed to the circuit shown in Fig. 5. 677 Res. J. Appl. Sci. Eng. Technol., 4(6): 675-685, 2012 Bmax VSV Cref + K SV C 1 sT SV C BSVC Bmin VSVC Fig. 4: Control model SVC ix ( t) i (t) v (t ) iL ( , t ) ic ( t ) L oa d C Fig. 5: FC-TCR equivalent circuit According to the figure, it is not obliged load to be linear and it is viable that analyze the non-linear load. All elements and branches current are depicted in the figure and it obviates description. It should be mentioned that if we assume that reactor L in Fig. 5 is variable then FCTSR-TCR configuration will be obtained. Therefore, circuit analysis will be similar for both FC-TCR and FCTSR-TCR modes. Firing angle " should be calculated such that drawn current from voltage source has to be declined to its minimum amount, and power factor correction is also reached. Suppose voltage and current density equations will be as follows (Gutierrez et al., 2002): v(t) = Vcos Tt J1 T i 2 (t ) dt Minimizing J1 is reached when: 0 (5) T 0 (i L ix ) i L dt 0 (8) ( 2 ) / V cos ( ) (i L i x ) dt (i L ix )dt 0 L / ( ) / 4V ( ) sin cos A(ix , ) L 2 2 From the Fig. 5, applying Kirchhof’s current law in TCR’s node we have: V (sin t sin ) t L iL ( , t ) V (sin t sin ) t 2 L (9) For " … B / 2, below equation should be zero. Substituting Eq. (7) in the above equation leads in: 0 i(t) = ix (t) + iL (" , t) i 2 ( t ) dt 2 Substituting il / &il / &" in Eq. (5), we get: (4) T 2 / T (10) where A(ix, ") is as follows: (6) A (ix , ) ( ) / w /w (7) ix dt ( 2 ) / w ( ) / w ix dt (11) Figure 5 shows function A(ix, ") and the amount of " satisfying in Eq. (10) expresses. It should be considered 678 Res. J. Appl. Sci. Eng. Technol., 4(6): 675-685, 2012 Fig. 6: Simulated circuit (12) SIMULATION RESULTS 250 200 150 100 50 00 -50 -100 -150 -200 -250 1.15 1.20 1.25 Time (s) In this section, six SVCs are tested on test case system. For simulations, FC-TSR-TCR circuit is considered with variable inductance L=0.1KL/T where KL=1, 2, 3, …, KLmax and fixed capacitor C=0.4/T. Also, load impedance is z = kz(1+2j)(–) where Kz=1,2,3,4. (Fig. 6). Considering circuit frequency equal to 50Hz, T = 100B, KL = 300, kz = 20, and " = 60o simulation results are obtained as follows Fig. 7 shows magnitude of current source. In Fig. 8 and 9, switching pulses for each thyristors and reactor taps voltage have been illustrated, respectively. Four switching pulses for parallel switches in Fig. 10 has been depicted. Finally, current and voltage outputs in Fig. 11 and 12 have been showed, respectively. Fig. 7: Current source 2.0 1.5 1.0 S F 0.5 0 -0.5 0.10 0.09 0.08 0.07 0.06 0.05 0.04 0.03 0.02 0 0.01 -1.0 Time (s) (a) Active power: First, we will discuss about how behavior these six branches of SVC on active power. Figure 13 shows active power in presence SVCs. It should be noted that shunt reactors applications in FC-TCR-TSC and FC-TSR-TCR circuits are entered using signals which are sent to the shunt switches. In the simulations, these reactors are switched out in 1.4 sec. Generally, in presence capacitor, range of active power is limited; this concept is clear in comparison Fig. 13a with b and TSC with TCR. Range variation TCR-TSC is average of Range variation of TCR and TSC, approximately; presence FC doesn't change this fact. Values of peak value, least value and fall time have been 2.0 1.5 S T2 1.0 0.5 0 -0.5 Time (s) (b) Fig. 8: Switching pulses for thyristors 1 and 2 679 0.10 0.09 0.08 0.07 0.06 0.05 0.04 0.03 0 0.01 -1.0 0.02 4V ( ) sin (1 LC 2 ) cos A(ix , ) L2 2 Source current that " = B/2 is a solution for Eq. (10). If iz is measured instead of ix, optimal amount of " will be obtained using following equation: Res. J. Appl. Sci. Eng. Technol., 4(6): 675-685, 2012 (a) (b) (c) (d) Fig. 9: Reactor taps voltage 680 Res. J. Appl. Sci. Eng. Technol., 4(6): 675-685, 2012 15 15 10 S Tap 1 Output current 10 5 0 5 0 -5 0.20 0.46 0.44 0.42 0.40 0.38 0.36 0.34 0.30 0.26 Time (s) 0.32 -15 0.28 0.18 0.16 0.14 0.12 0.10 0.8 0.6 0.4 0.2 -10 0 Time (s) (a) Fig. 11: Output current 500 400 300 200 100 (b) 0.46 0.44 0.42 0.40 0.38 0.34 0.26 Time (s) -200 -300 -400 -500 0.36 0.20 0.18 0.16 0.14 0.12 0.10 0.8 0.6 0 0.4 0.2 0 00 -100 0.32 5 0.30 Output voltage S Tap 2 10 0.28 15 Time (s) 15 Fig. 12: Output voltage 10 S Tap 3 1600 TSC 1400 1200 Active power 5 1000 0.20 0.18 0.16 0.14 0.12 0.10 0.8 0.4 0.2 0 0.6 0 800 TCR 600 TCR-TCS 400 Time (s) 200 1.6 1.8 2.0 1.8 2.0 1.4 1.2 1.0 1.6 15 0.8 0.6 0.4 0 0.2 0 (c) Time (s) (a) S Tap 4 10 1500 FC-TCR-TSR FC-TSR-TCR Active power 5 1000 0.20 0.18 0.16 0.14 0.12 0.10 0.8 0.6 0.4 0 0.2 0 FC-TCR 500 Time (s) (d) Fig. 10: Switching pulses for parallel switches 1.4 1.2 1.0 0.8 0.6 0.4 0 0.2 0 Time (s) listed in Table 1. TSC has maximum reduction after 1.4 sec; this behavior by installing FC is eliminated. Between first transient state to 1.4 sec, variation slope of SVCs is constant except TCR-TSC and FC- TCR-TSC. (b) Fig. 13: Comparison between active power (a) without capacitor and (b) with capacitor 681 Res. J. Appl. Sci. Eng. Technol., 4(6): 675-685, 2012 (a) (b) Fig. 14: Comparison between reactive power (a) without capacitor and (b) with capacitor Table 1: Values of control parameters of active power Value TSC TCR-TSC FC-TCR-TSC FC-TSR-TCR Peak 1121 1127 948 1000 Least 869 865 842 842 Table 2: Values of control parameters of active power Value TSC TCR-TSC FC-TCR-TSC FC-TSR-TCR Peak 2211 2155 1952 1975 Least 1607 1703 1677 1677 In Table 1, values of control parameters of TCR and FC-TCR haven't been presented; because these values are constant and are selected as base value for comparison. Magnitude of active power in presence TCR and FC -TCR are 922 and 851 kW, respectively. By considering results of Table 1, maximum and minimumpeak value in between SVCs devote for TSC and FC-TCR-TSC. TCR-TSC has maximum peak value. Least value of FC-TCR-TSC and FC-TSR-TCR are equal and these values are minimum least value. Table 2, maximum peak and least value are values of TSC and TCR-TSC, respectively. FC-TCR-TSC has minimum peak value. The least value of FC-TCR-TSC and FC-TSR-TCR, respectively is equal and this value is minimum least value. COMPARISON AND DISCUSSION To confirm capability of each one of SVCs, three statistical indexes are introduced. these indexes are APE and SMAPE as well as SSE. Values of peak and least of SVCs are compared with values of TCR. The behavior of TCR and FC-TCR in duration simulation are constant thus are proper base to comparison, also TCR has simple structure respect to FC-TCR. Reactive power: In this section, impact of SVCs on reactive power is analyzed. Figure 14 illustrates reactive power in presence SVCs. Due to Fig. 14, generally behavior each SVCs is similar with active power case. Range variation of reactive power in two times range variation of active power, approximately. TCR-TSC, and FC-TCR-TSC, respectively as well as TCR have warped to up 1.4 sec. In Table 2 values of peak and least of SVCs have been listed. Values of steady stat of TCR and FC-TCR are 1703 and 1800 kVAr, respectively. By attending to results of APE: APE used as comparison criteria, this parameters is defined following as: APE % 682 f TCR f f TCR other 100 (13) Res. J. Appl. Sci. Eng. Technol., 4(6): 675-685, 2012 11.76 2.77 2.77 0.77 1.39 FC-TCR FC-TSR-TCR FC-TCR-TSC 0 0.77 4.53 4.0 4.53 6.81 7.39 10 3.2 power, this fact in FC-TCR-TSC and FC-TSR-TCR is considerable, respectively. The SMARE of reactive power least of TSC-TCR and FC-TCR-TSC as well as FC-TSR-TCR, respectively. Figure 16 shows values of Table 4 as schematic. CONCLUSION In this study, two statistical indices are introduced to compare and discus haw impact of six branches of SVC on active and reactive power control. These indices are Absolute Percentage Error (APE) and Symmetric Mean Absolute percentage Error (SMAPE) and SVCs consist of Thyristor Switched Capacitor (TSC), Thyristor Controlled Reactor (TCR), Fixed Capacitor Thyristor Switched Reactor Thyristor Controlled Reactor (FC-TSR-TCR), fixed capacitor Thyristor Controlled Reactor ThyristorSwitched Capacitor, (FC-TCR-TSC), Fixed Capacitor Thyristor Controlled Reactor (FC-TCR) and ThyristorSwitched Capacitor and Thyristor- Controlled Reactor (TSC-TCR) , respectively. From results of Table 1-4, Reactive power has higher swap respect to active power. Variation range of reactive power is more than active power. In all cases, behavior of TCR and FC-TCR, respectively is constant after transient state. Presence of Fixed Capacitor (FC) is led to decrement of peak and least values; then by installing FC on SVC s reduce variation SMARE: SMARE is proper index to show magnitude difference. In this index, difference of two parameters is divided by sum of these parameters. In fact the SMARE normalizes absolute percentage error, 100 TCR-TSC TSC FC-TCR Table 4: Obtained SMARE from comparison between TCR and other SVCs Value TSC TCR FC-TCR FC-TSR FC-TCR -TSC -TSC -TCR Active Peak 9.74 10.00 1.39 4.06 4.00 Least 2.96 3.20 4.53 4.53 Reactive Peak 12.98 11.76 6.81 7.39 2.77 Least 2.90 0.00 0.77 0.77 where, |f|TCR and |f|other are peak and least values of TCR and other SVCs, respectively. Values of APE have been presented in Table 3. By considering results of Table 3, APE of peak values of reactive power is more than active power while this fact in least values was vice versa. The presence of FC has reduced APE in all cases, this reduction in active power is several times respect to reactive power. Maximum APEs of active and reactive power are TCR-TSC and TSC, respectively. The Table has been illustrated as schematic in Fig. 15. f TCR f other 44 Fig. 16: Obtained SMARE from comparison between TCR and other SVCs Table 3: Obtained APE from comparison between TCR and other SVCs TSC TCR FC-TCR Value -TSC -TSC -TCR FC-TSR FC-TCR Active Peak -21.58 -22.25 -2.82 -8.46 7.70 Least 5.75 6.18 8.68 8.68 Reactive Peak -29.83 -26.54 -14.62 -15.97 -5.70 Least 5.64 0 1.53 1.53 f TCR f other 12.98 2 Fig. 15: Obtained APE from comparison between TCR and other SVCs SMARE 2.9 -8.46 -5.75 -5.75 4 -14.62 -14.62 8 6 0 FC-TCR-TSC -22.23 -26.54 TCR-TSC TSC -30 -21.58 -25 -29.83 -15 -20 FC-TSR-TCR -10 9.74 10 -2.82 0 -5 12 2.96 0 1.53 5 14 7.7 7.7 8.68 8.68 1.53 6.18 5.64 5.75 10 Reactive-Peak Reactive-Least Active-Peak Active-Least Reactive-Peak Reactive-Least Active-Peak Active-Least (14) SMAREs of TCR and other SVCs have been presented in Table 4. Due to results of Table 4, peak value of TSC on reactive power and least value of TCR-TSC on reactive power have maximum and minimum SMARE, respectively. Then variation range of SMARE of reactive power is more than active power. In all case, SMARE of active power peak is more than related value of reactive 683 Res. J. Appl. Sci. Eng. Technol., 4(6): 675-685, 2012 range. In all cases, slope TSC-TCR curve is not zero and presence of FC does not change this fact. In summary, from the viewpoint of power flow control range, these six kinds of SVC can be classified as follows (from lowest to highest range), FC-TCR, TCR, FC-TCR-TSC, FC-TSR-TCR, TCR-TSC and the TSC, respectively. Bian X.Y., Tse C.T., Zhang J.F., and Wangc K.W., 2011. Coordinated design of probabilistic PSS and SVC damping controllers. Int. J. Elec. Power, 33(3): 445-452. Celli, G., F. Pilo and S.B. Tennakoon, 2000. Voltage regulation on 25 kV AC railway systems by using thyristor switched capacitor. Ninth International Conference on Harmonics and Quality of Power. Farsangi, M.M., H. Nezamabadi-Pour, Y.H. Song and K.Y. Lee, 2007. Placement of SVCs and selection of stabilizing signals in power systems. IEEE T. Power Syst., 22(3): 1061-1071. Gutierrez, J., J.C. Montano, M. Castilla and A. Lopez, 2002. Power-quality improvement in reactive power control using FC-TCR circuits, IECON 02 IEEE 2002 28th Annual Conference of the Industrial Electronics Society, pp: 880-885. Hammad, A.E., 1986. Analysis of power system stability enhancement y static VAR compensators. IEEE T. Power Syst., 1(4): 222-227. IEEE Special Stability Controls Working Group, 1994. Static VAr compensator models for power flow and dynamic performance simulation. IEEE T. Power Syst., 9(1): 229-240. Karpagam, N., D. Devaraj and P. Subbaraj, 2010. Improved fuzzy logic controller for SVC in power system damping using global signals, Electr. Eng., 91: 395-404. Kodsi, S.K.M., C.A. Ca#nizares and M. Kazerani, 2006. Reactive current control through SVC for load power factor correction. Electr. Pow. Syst. Res., 76: 701-708. Lahaçani, N.A., D. Aouzellag and B. Mendil, 2010. Contribution to the improvement of voltage profile in electrical network with wind generator using SVC device. Renew. Energ., 35: 243-248. Li, S., M. Ding, J. Wang and W. Zhang, 2009. Voltage control capability of SVC with var dispatch and slope setting. Electr. Pow. Syst. Res., 79: 818-825. Mahanty, R., 2010. Modified static VAR compensator using a large value AC capacitor. Electr. Pow. Syst. Res., 80: 240-247. Montafio, J.C., J. Gutierrez, A. Lopez and M. Castilla, 1993. Effects of voltage-waveform distortion in TCR-type compensators. IEEE T. Ind. Electron., 40(3): 373-383. Modi, P.K., S.P. Singh and J.D. Sharma, 2008. Fuzzy neural network based voltage stability evaluation of power systems with SVC. Appl. Soft Comput., 8: 657-665. Preedavichit, P. and S.C. Srivastava, 1998. Optimal reactive power dispatch considering FACTS devices. Electr. Pow. Syst. Res., 46: 251-257. Quintela, F.R., J.M.G. Are'valo and R.C. Redondo, 2008. Power analysis of static VAr compensators. Electr. Pow. Energ. Syst., 30: 376-382. NOMENCLATURE SVC TCR TSR FC MSVC SC FLC PSS APE RSMD MISO DFN KSVC TSVC Xsl Vt Vref Bind Bcap FACTS STATCOM SMIB AVR PSHNN EMTP SMAPE PSO NSPSO NSGA TCSC Static VAr Compensator Thyristor Controled Reactor Thyristor Switched Reactor Fixed Capacitor Modified SVC Synchronous Condenser Fuzzy logic controller Power System Stabilizer Absolute percentage Error Root-Mean-Square Error Multi Input Signal Output Dual-Function Neuron Gain constant of SVC Time constant of SVC Equivalent slope reactance Node voltage magnitude Reference voltage magnitude Inductive susceptance Capacitive susceptance Flexible AC Transmission System Static Synchronous Compensator Single-Machine Infinite-Bus Automatic Voltage Regulator Self-Organizing Hierarchical Neural Network Traditional Electromagnetic Transients Program Symmetric Mean Absolute Percentage Error Particle Swarm Optimization Non-dominated Sorting PSO Non-dominated Sorting Genetic Algorithms Thyristor Controlled Series Capacitor REFERENCES Abido, M.A. and Y.L. Abdel-Magid, 2003. Coordinated design of a PSS and an SVC-based controller to enhance power system stability, Electr. Pow. Energ. Syst., 25: 695-704. Albasri, F.A., T.S. Sidhu and R.K. Varma, 2007. Performance comparison of distance protection schemes for shunt-FACTS compensated transmission lines. IEEE T. Power Deliver. 22(4): 2116-2125. Benabid, R., M. Boudour and M.A. Abido, 2009. Optimal location and setting of SVC and TCSC devices using non-dominated sorting particle swarm optimization. Electr. Pow. Syst. Res., 79: 1668-1677. 684 Res. J. Appl. Sci. Eng. Technol., 4(6): 675-685, 2012 Venayagamoorthy, G.K. and R.J. Sandhya, 2008. Dualfunction neuron-based external controller for a static VAr compensator. IEEE T. Power Deliver, 23(2): 997-1006. Vijayakumar, T., A. Nirmalkumar and N.S. Sakthivelmurugan, 2010. Reactive power control using FC-TSR-TCR. Res. J. Appl. Sci. Eng. Technol., 2(1): 1-4. Yuan, Y., G. Li, L. Cheng, Y. Sun, J. Zhang and P. Wang, 2010. A phase compensator for SVC supplementary control to eliminate time delay by wide area signal input. Electr. Pow. Energ. Syst., 32: 163-169. Zhang, J., J.Y. Wen, S.J. Cheng and J. Ma, 2007. A novel SVC allocation method for power system voltage stability enhancement by normal forms of diffeomorphism. IEEE T. Power Syst., 22(4): 1819-1825. Zhou, E.Z., 1993. Application of static VAR compensators to increase power system damping. IEEE T. Power Syst., 8(2): 655-661. Zou Z.Y., Q.Y. Jiang, Y.J. Cao and H.F. Wang, 2005. Normal form analysis of interactions among multiple SVC controllers in power systems. IEE Proc. Gen. Trans. Distrib., 152(4): 469-474. Rahima, A.H.M.A., E.P. Nowicki and O.P. Malik, 2006. Enhancement of power system dynamic performance through an on-line self-tuning adaptive SVC controller. Electr. Pow. Syst. Res., 76: 801-807. Robak, S., 2009. Robust SVC controller design and analysis for uncertain power systems. Control Eng. Pract., 17: 1280-1290. Singh, J.G., S.N. Singh and S.C. Srivastava, 2007. An approach for optimal placement of static Var compensators based on reactive power spot price. IEEE T. Power Syst., 22(4): 2021-2029. Sun, L.Y., S. Tong and Y. Liu, 2011. Adaptive backstepping sliding mode H4 control of static VAr compensator. IEEE T. Contr. Syst. T., 19(5): 1178-1185. Teleke, S., T. Abdulahovic, T. Thiringer and J. Svensson, 2008. Dynamic performance comparison of synchronous condenser and SVC. IEEE T. Power Deliver, 23(3): 1606-1612. Thomas, P.Y., J., P. Conard, F. Labrique and H. Buyse, 1994. Analysis of a Three Phase TSC-TCR static VAR sompensator by recurrences theory, Proceedings of 7th Mediterranean. Vachirasricirikul, S., I. Ngamroo and S. Kaitwanidvilai 2010. Coordinated SVC and AVR for robust voltage control in a hybrid wind-diesel system. Energ. Convers. Manage., 51: 2383-2393. 685