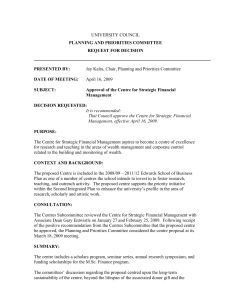

Formative Evaluation of the Networks of Centres of Excellence — Centres of

advertisement