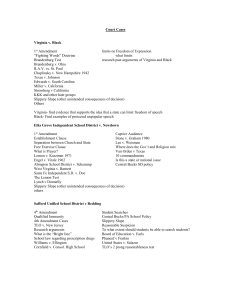

THE MECHANISMS OF THE SLIPPERY SLOPE Eugene Volokh

advertisement