K S A C

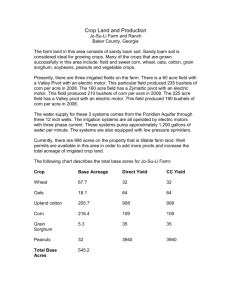

advertisement