Document 13261579

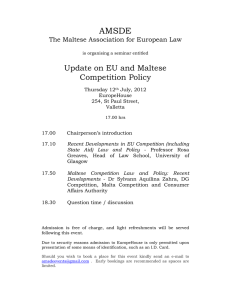

advertisement