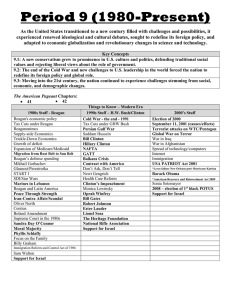

“Who Controls Whom?”

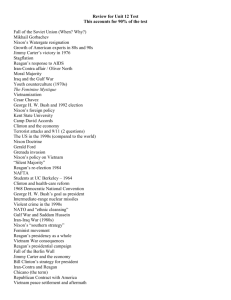

advertisement