The Effect of Emigration from Poland on Polish Wages ∗ Christian Dustmann

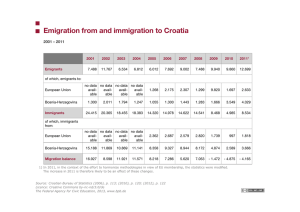

advertisement