Multi-hazard concepts and assessments

Aon Benfield UCL

Hazard Centre

Multi-hazard concepts and assessments

Summary.

Humanitarian and development non-government organisations (NGOs) are largely failing to incorporate multi-hazards in their policy and programmatic work.

This is due to a combination of institutional ways of working, the constrained spatial and temporal scales of current hazard analysis, and the limited incorporation of physical science in their assessments of hazard and risk. Exciting advances are expected by adopting methods of exposure analysis that are analogous to those already being used in the insurance and reinsurance sectors.

1. ABUHC and CAFOD Partnership

The ABUHC and the Catholic Agency for Overseas Development (CAFOD) established a partnership in 2008 for the purposes of integrating scientific knowledge and research on disaster risk reduction and climate change adaptation into CAFOD’s programmatic and policy work.

Natural hazards are expected to have greater impacts in the future, and so there is increasing advocacy for incorporating scientific, multi-hazard assessments in order to identify and to evaluate emergent risk. For effective application, NGOs require guidance on how to conduct a multi-hazard assessment. The ABUHC and

CAFOD partnership has thus initiated a research programme to determine how multi-hazard assessments can be integrated into NGO procedures.

Hazards in the Philippines. Left to right : Mt Mayon volcano and, in the foreground, coastal defences for Legaspi City. Coastal settlements at risk from flooding, Tobacco. Multiple hazard map of the Philippines.

Photos: M. Duncan; Map: UNOCHA.

2. Multi-hazard concept

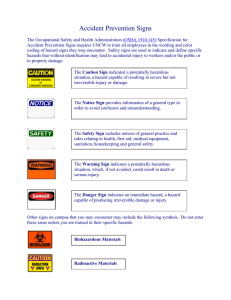

Complete evaluations of multi-hazard impact do not simply add together the impacts of the hazards treated independently. They also take account of how interactions among hazards can further increase their cumulative impact. We have recognised four key types of interaction, of which three normally apply to short-term behaviour:

3. Multi-hazard assessments

NGOs typically adopt qualitative methodologies when collecting and analysing data for community-based assessments of risk. We have analysed how these methodologies have been applied by practitioners based in the UK and the

Philippines. The results show that, although the methodologies can account for more than one hazard acting independently, they do not readily account for interactions among hazards.

The low awareness of hazard interactions appears to result from an almost total reliance by NGOs on community knowledge alone. Such knowledge naturally favours events that have occurred within the given community and within living memory. The resulting hazard analyses thus tend to be constrained to local areas and to short time frames. As a result, they rarely account for hazards with long return times and for the potential for a hazard outside the study area to trigger another hazard within that area – whether by association, causation or amplification.

Association : hazards that increase the probability of a secondary event, but which are difficult to quantify; e.g. stress changes after an earthquake increasing the probability of eruption at a neighbouring volcano.

Causation : hazards that generate secondary events, which may occur immediately or shortly after the primary hazard; e.g. landslides triggered by earthquakes.

Coincidence : the simultaneous occurrence of independent hazards; e.g., the coincidence of a windstorm with a volcanic eruption generating an additional hazard from mudflows.

The fourth interaction applies to long-term behaviour:

Melanie Duncan meeting with communities displaced by typhoontriggered lahars from Mt Mayon. Photo: M. Duncan.

Amplification : long-term feedbacks between hazards that exacerbate subsequent impacts; e.g., flooding-induced coastal erosion may increase the impact of tsunamis on a particular coastline.

UK-based practitioners are further concerned that the unconstrained application of science may disturb the cultural fabric of a community. Yet studies from the Philippines indicate that scientific knowledge provides a complementary approach to interpreting community data and may identify potential hazards with which a community are not familiar.

Key steps to enhancing current hazard assessments, therefore, are for NGOs to include scientific knowledge in their current methodologies and to develop innovative ways for incorporating that knowledge, including forms of exposure analysis that are now standard in the insurance and reinsurance sectors.

More information?

Contact: Melanie Duncan and Stephen Edwards (melanie.duncan@ucl.ac.uk)

Aon Benfield UCL Hazard Centre, University College London, Gower Street, London WC1E 6BT, UK