The Potential for Improved Water Management Using a Legal Social Contract

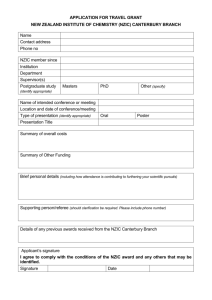

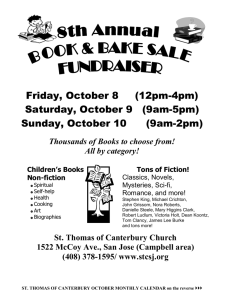

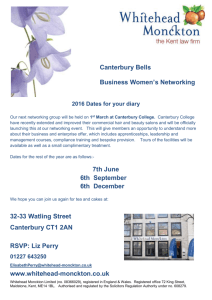

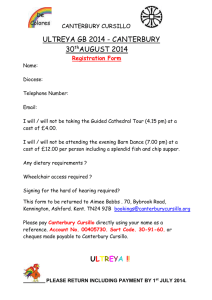

advertisement