Presentation Stockholm September 2012 Presentation slide +

advertisement

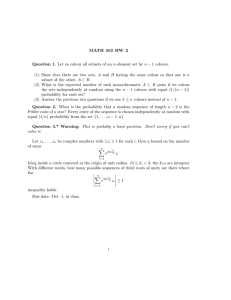

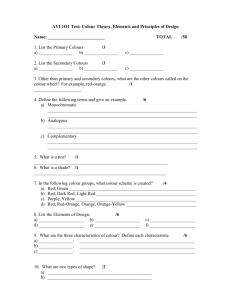

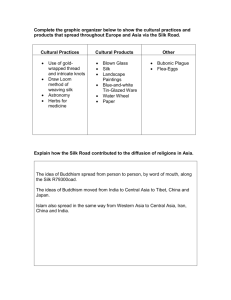

Presentation Stockholm September 2012 + Presentation slide Here are some early modern names for colours I stolen from Robert Finlays article ”Weaving the Rainbow: Visions of Color in World History” (Journal of World History 2007). He mentions: horseflesh, goose turd, rat’s colour, pea porridge as terms used in 18th century England. In France they had Paris mud, goose-droppings, In China they had camel lung, rat skin, nose mucus, dribbling spittle These names indicate not only lacklustre colours, washed out green, grey and brown. They also indicate the social status of those who wore those clothes. It was poor people the colours of who were reminiscent of mud, turd, spit and porridge. Many dyes that produced bright colours in the early modern period, such as ultramarine made from a mineral called Lapis Lzuli, minded in Afganistan, and known as the diamond of all colours, was very expensive. As was the fibre that was most responsive to the application of dyes, who gave it a particular shine, namely silk. The techniques involved in producing silk textiles originated in China but had over the cause of the centuries it spread west wards, to Byzantine, the Mediterranean world. Silk became the preferred material in the production of luxurious textiles, a production that by the 18th century was centred in places like Lyon and London,. This does not mean that Chinese silk ceased playing a role in Europe. In fact the 18th century saw a revival of this specific form of goods, namely in the form of silk textiles imported by the East India Companies. In this paper I am going to look closer at the this import and particularly the colour schemes of Chinese silk textile. + Project slide My interest in this stems from work I am conducting as part of Post doc project located at the University of Warwick and headed by Maxine Berg. The project is called Europe’s Asian Centuries, Trading Eurasia 1600-1830. In a very broad sense the project is about the effects of the Asian imports on European consumption. It is about how consumer demands in Europe shaped the production of luxuries and semi luxuries in Asia but also how the Asian import triggered product developments in Europe. The development of European cotton textile production, particularly in Britain, and European porcelain production are the best known example of such technology transfer. I am one of three post docs who are researching the European East Indian companies. My remit is to focus particularly on the Scandinavian companies, the Danish, Asiatiske kompaniet and the Swedish East India company. + Text slide So why have I focused on the colour schemes of silk material? The colour schemes offers us a way of understanding several processes. Firstly, the 18th century was a period when new dyes developed in the wake of growing consumer demands. Dyes such as Preussian Blue, Saxon Green… Interest in colours for decorative measures is for example very pronounced in The Royal Society of Arts in London, an organisation that encouraged the development of new dyes and varnishes among other things. The attention paid to what things looked like, the surface and shades of colours of objects, reflects the centrality of consumption to how production methods developed in the 18th century, something which Maxine Berg have been at the forefront researching. But it was not only a matter of production. Central to colours and dies was natural history and sciences. On a very practical level, taxonomy, species identification, was instrumental in the search for plants and insects that could be used in producing dyes. There is a political economy at play here too, naturalists were involved in looking for new ways to exploit nature, to produce new stuff, benefitting their home countries. There was a also some deeply philosophical issues at stake, what constituted a colour? Newton had used prism to break down the different wave length of lights and concluded there were 7 principle colours. Other followed suits, drawing on their experiences from natural history, as well as manufacturing industry, the contributions to the praxis and theories of colours came from a wide array. Great efforts were made to create systems for identifying and naming colours. In other words, the Europe to which the multi coloured Chinese silk arrived was a very dynamic place in terms of new technics, new sources and new theories about colours, it was also a place where consumption influenced production. It is against this backdrop I would like discuss the names of colours and varieties of colours on the Chinese silk for sale. Secondly, and related to the first aspect, the colour of Chinese silks offers an way into understanding the market for the Chinese textiles in Europe, and the extent to which it was dictated by trends and fashions. That European tastes mattered and that it shaped production in China has long been established when it comes to the porcelain. Chinese producers picked up trends and demands quickly. Soup terrains, an object alien to the Chinese kitchen and cuisine, and European styled decoration, was added to the usual blue and white stuff. Meissen porcelain, the first true porcelain produced in Europe was soon copied in China. If our assumption is that trends and colour schemes in European clothing and silk manufacturing changed in quite a dynamic way, with impulses extending from Lyon, Paris and London, then my question is, to which extent did the Chinese producers and whole sellers of silk and the East India Companies respond to these impulses? + Scandinavian East India Company It is with these questions in mind I have started looked at the Scandinavian East India companies. The Swedish established 1731, traded almost exclusively with China, while the Danish Asiatiska Compagni, traded with both India and China in the 18th century. It is worth underlining that both the Danish and the Swedish company largely imported for an European market, between 70 and 90 % of all the Asian goods brought to Copenhagen and Gothenburg was re-exported. So although the Scandinavian companies were located in a “fashion” or “trend periphery”, they were trading on behalf of consumers in more centrally located placed. Of course there was a limit to how fast any East India Company could respond to changing trends. It took on average 2 years for a ship to make the round trip to Canton. In other words, in so far the import of Chinese silk was dictated by changing trends in Europe. There is also an issue of import restrictions on Chinese silk, both in Scandinavia, for domestic use, and in places to which the goods was re-exported. Exactly how these restrictions effected the import is hard to tell, particularly since smuggling was rife. In the Swedish case, which I will focus on largely on here, there is a notable decline in the import of Chinese silk in the 1750s. To which extent this was an effect of the higher import duties in Sweden after a change of regulation in mid 1740s or reflecting the introduction of bans in other countries to which the silk was re-exported is hard to tell. I have at this stage not established where the Swedish silk ended up, where it was consumed. Anecdotal evidence suggest that loads arrived to the Dutch republic, a port of call for a lot of the Chinese goods brought to Europe by the Swedish and the Danish companies. What is clear is that the import of silk from China to Gothenburg flourished in the 1730s and 40s and it is also this period that I have focused on particularly. My main sources is a rather unique material, a selection of preserved sales catalogues, describing goods for sale, who bought it and for what price. All in all I have 21 volumes of sales catalogues covering in 16 years, from the period 1733 to 1759. + List of Names (hand out) What then can this material tell us about colours, trends and prices on Chinese silk? On page one and two I listed all the colour references found in material relating to the Swedish East India Company. The list give you some indication of the variety of colours that the Chinese silk came in. As you can see colour terms are listed in three different columns and in three languages or four if you take into account the frequency of French terms in all the three different columns. Why is this the case? It has to do with the origin of this list. The market for the goods brought over by the Swedish East India Company was largely located outside the domestic realm, explaining why its catalogues were published in German for the first 13 or 14 years. The first sales catalogue published in Swedish is from 1747, exactly what brought about this change I don’t know. What is well known however is that the merchants who operated the company to a not small extent originating from Scotland. The English terms listed in the third column is from a pack list, found in the archive of the Tham family, a family with several members working for the Swedish East India Company. The use of English in the packing list might reflect the fact that Tham was working with a team of Scottish super cargoes in Canton, and their working language was English. The English colour terms listed here are however not unique, rather many of the same terms were used by the English East India Company in for example ordering lists sent to Canton with the British East India ships that I have looked at. What I have seen so far suggest that the Danish company used a very similar nomenclature for colours. An I have also reasons to believe the same colour terms were used by the Dutch and company when they ordered goods from China. In other words, across all the European East India companies a similar terminology was used in specifying what colours the silk purchased in China was to have. As the sales catalogues suggests, the same terms were also used when presenting the goods for sales. + Slide French Names This Pan-European terminology for colours is to a not small extent actually French. I am going to spare you my pronunciation of these terms but here is a selection of the French vocabulary used in Europe and as far as I gather in Canton. Poneceau (French for Poppy) Couleur de Rose Couleur de Chair Paille Blomerant from French Bleu mourant Turqvin blue probably from Turquin marble Mazarin blue, dark blue, named “in honour of “ Cardinal Mazarin, Richelieu’s predecessor My assumption is that the French terms marks the traditional dominance of French fashion at this time, and that this French system for distinguishing colours, shaped the silk trade between China and Europe. So far in my work I have found very little evidence Chinese terms was used in transactions. Without knowledge of Chinese it is hard to compare the colour terminologies in China and Europe in the 18th century but we can take the example of the term “tea colour”. It was used in hand books for how to dye silk from the 17th century but can also be traced in administrative material from Canton, describing silk that had been smuggled to the European ships. It is possible that tea colour refer to a yellow shades. Yellow and red were colours which traditionally were exclusive to the Chinese court. As the list suggest this does not seem to have stopped the trade in silk material with these colours, taking place between Hong merchants and European super cargoes, we find several shades of red and yellow on the list. The list of names on page 1 and 2 suggest a wide variety of colours in which the Chinese silk came in. Of course the number of colours on offer varied pending on which quality, or type of fabric you look at. The most variety in terms of colour on offers for different types of textile I have found is from the sale of silk brought back by the Swedish East India Company. Different sorts of Damask came in 21 out of 26 available colours, Taffeta in 17 out of 26 colours and Padusoys in 23 out of 26 colours. If you add all the different pieces of silk and the colours they came in together then you get this result. + Slide with circle diagram It was quite fiddly but I did try and match the colour of the segments in the circle diagram with the something reminiscent of what I thought the names refers to. The overall visual impact of all these colours must have been spectacular. Particularly since they were all exhibited together for sellers to inspect, prior to the auction, in the house of Johan Friedrich Bruun, situated at the Great Harbour in Gothenburg 1748. As you can see the most common colour was one called sky blue. To which extent it marks the fact that Sky blue was believed to be the most popular among consumers, a best seller on the continent where I assume quite a lot of the Chinese silk brought to Gothenburg ended up is hard to tell. We need here to take into account that the silk was usually sold in lots, containing maybe 30 pieces, and with a variety of colours in them. + + Lots different prices The sales catalogues allow me to compare the price for different lots containing different variations of colours. As a general rule it seems to be the case that the lots that contained the greatest variety of colours sold for the highest price. This example is from the catalogue of 1748, of XXX. As you can see the price per piece in the lot containing silk in 16 colours was 20% more expensive than the one only containing silk in 6 colours How much did the colours scheme changed over time? + Slide change over time If we look at the two last pages of the hand out we can get some idea of changes over time. Now, note that this is work progress. The order in which the colours are listed reflects how well represented they are. So if we look at 1736, Cherry red is at the top of the list. Out of the 130 or so categories of silk textiles (the reason they were so many has to do with the silk coming not only in different qualities, mainly Satin, Taffeta and Damask, but also in different lengths and widths) 51 of them contained silk with a cherry red colour. One could say that cherry red was the best represented colour among the 24 colours that year. It does not mean cherry red was the single most frequent colour in the cargo since some of the 130 or so different categories of textiles for sale only contained a handful of silk pieces, while others contained several thousands. + Slide of list of names (previous) I want to end this presentation by returning to the nomenclature of names of colours. The list of names and their frequency does give us a history of a different kind. Here is a history of globalisation. Take the colour Karmine or Crimson in English, it was generally a colour produced with a dye made from an insect with the scientific name Kermococcus vermilis planchon. It had been used for red colours including silk on the whole of Eurasia continent, since the prehistoric period, including China. The dye was called Kermes and many European and Asian languages have a name for red which is derived from the word kermes, including here Karmine and Crimson. Historical word books and etymological research suggests that many of the colour terms I have listed evolved in close connection to textiles and silk. One of the first references to sky blue in the Swedish historical word book, produced by the Swedish Academy, SAOB includes a description of a sky blue blue dress with silver decorations. (Pufendorf Hist: “himmelsblå tygklädning med påkastade silverkvistar”). However, judging by SAOB, quite a few of the terms I have found were not commonly used in Sweden in the 18th century, or at least not for silk. The word book is by no means fool proof, however this supports the fact that a lot of the silk material was re-exported. One of the sources in which quite a few of my colour terms make their debut into the Swedish languages (according to SAOB) is in a book by the Swedish naturalistm Westring, published 1805. + Slide Westring The book contains advice and recipes on how to use lichen that grew in Sweden to colour wool, linen, and silk. Westring turned to both mistresses of the house, dying or re-dyeing household textiles, and manufacturers of finished goods, both groups he assumed wanted a colour on their silk with “the solidity and shine reminiscent of the Chinese silk”. (”På silke få de ofta lika fasthet och glans, som de Kinesiska.”. Here is an underlying ideology very much in line with the cameralist understanding of nature and consumption, an ideology rothed in 18th century thinking. Westring was in many ways a student of the Swedish naturalist Linnaeus. IT is about using material that could be collected in forest and fields at home. But it does also mark a shift, it suggest access to silk material on general level, a different form of consumption. With advise on hot to produce Jonquile and Celadon shades it also marks a distinct shift away from pea porridge and goose turd.