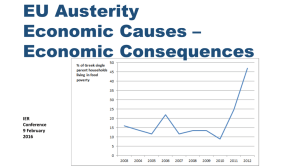

Report on the High Level Mission to Greece INTERNATIONAL LABOUR OFFICE

advertisement