DREAM E F I

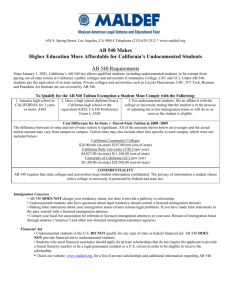

advertisement