Research Article: Social Sustainability, Urban Regeneration and

advertisement

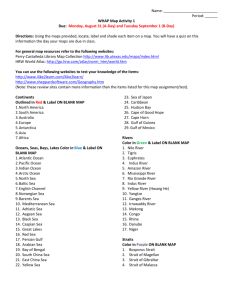

Research Article: Social Sustainability, Urban Regeneration and Postmodern Development approaches for Strait Street, Valletta. by Mr Jonathan Caruana BSc Geography and Environment (London) Introduction Walking along the numerous shops along Republic Street in Valletta during the day, one can be forgiven for failing to notice a narrow street that runs parallel to it. Once within however, one immediately senses there is a history behind its deteriorated facades. This degradation is the result of years of neglect following the street’s fall from grace, which started in the aftermath of World War 2, when thousands of sailors visited looking for a much needed respite from service and war duties. However, Strait Street, or as more commonly known by locals, Strada Stretta, has in the last years slowly started regaining its reputation as the capital’s main spot for entertainment, following the opening, or re-opening, of a number of bars and restaurants. Figures above respectively showing the area in front of ‘Tico Tico’ during a typical evening and the lower part of Strait Street (Source: Schofield and Morrissey 2013 / Author) Bearing in mind that Valletta has been awarded the status of European Capital of Culture for 2018 for which a series of events and projects are being prepared, lately, there has been a public outcry calling for Strait Street’s regeneration. The term ‘regeneration’ nevertheless, does not solely involve the restoration of stone fabric and creation of visually attractive spaces, but also giving new uses to abandoned buildings. Jane Jacobs (1992:194) stated how ‘amongst the most admirable and enjoyable sights to be found along the sidewalks of big cities are the ingenious adaptations of old quarters to new uses’. These projects however should be preceded by careful consideration to various issues. Behind ‘regeneration projects’ lies the danger of urban areas converted into new stylish housing and entertainment spaces - or as Featherstone (2007) called them ‘the centrepiece for consumer culture lifestyle’. This creates a haven for new rich and the upper-middle class but also pushes out original inhabitants less able to afford housing and maintenance costs, a process usually referred to as ‘gentrification’. Methodology It is with these considerations in mind that this study sought to investigate the social and political reality present at the moment in Valletta. It also makes an analysis into how the social aspect within the sustainability debate is integrated into urban regeneration projects and the implications of adopting a postmodern type of regeneration. The paper points out the powerful advantages of urban regeneration and postmodern development projects to revive derelict areas and promote cities, but also highlights the dilemmas that emerge from such processes, such as a lack of social inclusion and cultural homogeneity, as well as gentrification. To achieve this, a mixed method of research was adopted for this study. The main vehicles of research used were an in-depth review of relevant literature as well as established research methods such as semi-structured interviews and online questionnaires. A more controversial method in the form of structured observation within the street under study was conducted for further data triangulation. The paper used Strait Street as a case study. The literature review enabled an examination into the relationship between the topics of study. Findings Social sustainability, urban regeneration and postmodern development According to Davidson (2010:872) due to the current diversity in interpretation ‘sustainability has become an expansive and slippery concept’ on the basis of which ‘a variety of conceptual understandings have been developed’. This is leading to social sustainability being translated in various manners resulting in various justifications being made for particular decisions regarding interventions and investments in the material and social fabric of cities, whereas instead closer attention should be paid to practical, operational and perhaps less economically friendly aspects of social sustainability. In fact, the simplest, yet complete, explanation about what social sustainability entails is given by Woodcraft et al. (2012:35) when noting how ‘social sustainability combines design of the physical environment with a focus on how the people who live in and use a space relate to each other and function as a community’. Polese & Stren (2002) note how whilst it is often assumed that spatial restructuring inevitably leads to economic development, and subsequently to social development, this line of thinking is questionable and unsupported by experience elsewhere. Power and Willmot (2007:58) argue how reconciling the improvement of poor neighborhoods through the eradication of visible problems with the countervailing needs of regeneration and community may be the biggest challenge facing lowincome communities and government approaches to neighborhood renewal. Back in the early 1980s Grigsby et al. (1983) noted how the terms ‘deterioration’ and ‘decline’ both raise some sticky definitional issues. They also noted how the worsening of old neighborhoods within the market increases as they gradually lower on a scale of relative quality. This leads to an absolute negative change in the physical or social quality of an area, characterized by a sequence of events which leads to a price decline and eventual housing deterioration. Glaeser and Gyourko (2005) note how this decline is more persistent than growth because the durability of the buildings means that it can take decades for negative urban shocks to be fully reflected in urban population levels, with negative shocks tending to affect prices more than population. Neal (2003) notes how cities are today embarking on a policy of urban renaissance which has at its heart the re-establishment of these previously neglected areas, by attempting to turn such areas into thriving and attractive urban districts. This renaissance, however, is based on consumption and visual attractions (Bairner 2006). In turn, questions are being raised about how socially sustainable this renaissance can be. García (2004) identifies a range of spatial, economic and cultural dilemmas associated with regenerating areas which are suffering from decline. These include gentrification, the encouraging of consumption over production, and support for ‘ephemeral’ - and perhaps quick fix - activities such as events and festivals over ‘permanent’ activities such as the creation of long term cultural legacies in the shape of permanent infrastructures. These measures form part of a broad philosophy of urban transformation, which has been inspired by artists, urban designers, visionary architects and social entrepreneurs, leading to the cityscape as an arena for a whole range of economic, social and cultural activities. On his part, Evans (2003:417) considers these as an exercise in ‘hard branding’ by cities, in an attempt to capitalize on commodity fetishism and extend their brand life, both geographically and symbolically, or what some call ‘postmodern development’. Bramham and Wagg (2009:31) argue that postmodern development ‘facilitates a renaissance for cities fitting the demands of economic and technological restructuring’. Among its central features is the collapse –or perhaps an apparent collapse - of the hierarchical distinction between high and mass/popular culture, and a shift towards a stylistic promiscuity that favours eclecticism instead of doctrine (Featherstone 2007). Policy, investment and development With the aim of satisfying an increased demand for new city imagery, experiences and style, Valletta, like other European cities faces intense competition to attract tourists as well as financial investments. These can be sought by bolstering its image as centre for cultural innovation. Grand projects such as the recent City Gate project help in this purpose, but without effective measures in other areas, the regeneration efforts at the entrance of the city could become an isolated project without any effective links to the rest of the urban area. The question remains as to what forms of regeneration are necessary. From an Online Questionnaire carried out in this research, a strong consensus emerged that a regeneration of Strait Street should emphasise on both commercial and cultural activities. Thirty per cent ‘strongly agreed’ on an emphasis on commercial activities, whilst 53% ‘agreed’. Similar, but more balanced, responses were received calling for an emphasis on culture, with 41% agreeing and 47% strongly agreeing. Above: When asked if a regeneration of Strait Street should emphasise on commercial activities (such as retail, cafeterias, bars, restaurants, etc.) there was a clear consensus for such type of regeneration (Source: KwikSurveys.com / Author) Above: When asked if a regeneration of Strait Street should emphasise on cultural activities (such as artisan shops, small theatres, artistic displays, etc.) here was also a clear consensus for such type of regeneration (Source: KwikSurveys.com / Author) This combination between commercial and cultural activities was also pointed out during interviewing, with particular reference made as to how Strait Street could be converted into a ‘creative cluster’. Nevertheless, on major problem remains the amount of vacant spaces present within the street, especially on the lower part (approaching St Elmo). Keeping in mind the problems with vacant buildings or ones which do not meet modern habitation standards present in the lower area, current Grand Harbour Local Plan (MEPA 2002) policies proposed a number of incentives which could have helped to regenerate the area. These included ‘lift provision, tax rebates, or grants on eligible works, the possibility of ‘soft’ loans for specified housing-related work as well as support for the purchase or use of adjacent unused properties’. In the lower area, current policies aim at the retention of spaces for residential purpose however the numbers of existing vacant spaces suggest such policies have not worked. With new Local Plans expected to be issued soon, it is expected new policies build on such initiates, whilst tackling issues in which current policies have failed. Entertainment Research in this study suggests there is a clear preference for entertainment in Strait Street, as opposed to a ‘retail’ space. The percentages obtained during the online questionnaire suggest the history of the place, as well as the number of bars and restaurants which have recently opened in one particular section of Strait Street, mean it is inevitably associated with this type of use, which makes it fundamental for any revival of the city’s nightlife scene. This concentration of entertainment spaces present in the area is not found anywhere else in the city, which makes Strait Street different from other spaces in Valletta. As per questionnaire response, most of those who visit Strait Street for leisure purposes fall within the 18-44 age bracket, with reasons for the lack of visiting ranging between the street being out of their way (mostly in view of their workplace), a lack of shopping outlets (often preferring Republic Street for such purpose), or simply because there is nothing of interest to them in the area. Almost half of the respondents (49%) stated they preferred Strait Street during the night, whilst 69% of the respondents would like to see more ‘entertainment spaces’ such as bars and restaurants in the area. Above: Leisure as the main purpose for respondents for those aged between 18-44 years, for passing through Strait Street whilst in Valletta, grouped by age (Source: Author) Above: Figure shows how ‘entertainment’ is the respondents’ preferred option for Strait Street (Source: KwikSurveys.com / Author) Amongst other suggested uses, the majority were connected to culture with the most popular being ‘art galleries’, ‘theatres’ and ‘cinemas’. One respondent expressed the wish to see more ‘high quality bars’ and ‘fine-dining restaurants’, whilst ‘offices’ and places for ‘touristic accommodation’ were also mentioned. For sure, Strait Street’s past has now become its main attraction. It is this sense of nostalgia, of being transported back in time, which fuels the imagination of its visitors. As a result this is often being reflected in the style adopted by entertainment spaces opening in the area. It is also why during interviews, there was a strong sense of scepticism about the possibility of these spaces co-existing with global corporate entities such as retail shops and fast food outlets, especially since a different type of clientele frequents the area, which could be detract them from coming to their places as a result. The absolute importance of both presentation and appearance was emphasised during interviewing, in terms of keeping the feel of the place but also in giving it a contemporary mode, since as one interviewee noted, it is ‘the appearance of the place determines the type of clientele you attract’. When discussing the type of market Strait Street should be looking at, it was noted that whilst visitors will come from all sections of society, development can also be ‘directed’ towards certain sectors in the market. In terms of tourism, publicity and embellishment increase visitor numbers however, where locals are concerned, the discourse changes. Here there is instead a wish to attract the ‘right’ type of people. This wish was also expressed openly from the public reaction witnessed during the ‘new Paceville’ debacle in early 2014. From the interviews conducted, it is clear there is a vision for Strait Street to become a place where ‘certain’ types of people can meet, have fun and participate in cultural events. This ‘niche in society’, as one interviewee called it, does not look for fast food outlets, but instead is attracted by stylish decoration and appearance. Here comparisons can be made with what Chatterton and Hollands (2003) describe as ‘white-collar service classes’, ones who are eager to distinguish themselves from other social groups. Regeneration and residents Of course these commercial activities should form only part of any regeneration project envisaged for Strait Street. One cannot underestimate the importance of creating (if possible) a harmonious relation between the existing residents and the ongoing commercial developments. A balance needs to be struck between the two. During interviewing, a resident argued the European Capital of Culture event in 2018 will not play a big role in Strait Street’s regeneration, since there is not much culture in the way the place is changing, instead comparing its revival to a conversion into a ‘new Paceville’. The resident also lamented a lack of consultation with them regarding the type of developments being carried out in the area. Of course, urban development based only on commercial outlets does not guarantee long term social sustainability. The gradual decrease in population and a lack of provision of decent and affordable housing in the area also needs to be addressed. This has perhaps been the main driving degenerative force from which the city has suffering. One of the objectives of the European Capital of Culture event should be to attract residents back to the city, the population of which has been in decline for the past decades1. This would help give life back to the number of buildings in the city, particularly in Strait Street, presently abandoned and left to slowly deteriorate. As was the case with other cities - the Tribal district in Madrid being a prime example – the gradual emptying of property creates an excellent business opportunity for owners looking to sell their property in the area and for business developers with enough financial muscle to buy and redevelop them into commercial spaces or new spacious and often luxurious - housing properties. On their part, landowners will be more than willing to sell to the right buyer, in order to compensate for the losses made by keeping the building empty. In turn, this new demand for property in the city will slowly start changing the urban landscape of such areas. Slowly, as these areas will start to be regenerated, the desire for property in Valletta will begin to increase, as will pressure to sell and re-develop occupied houses and flats. As the price for buying or renting property will also increase, the few remaining residents, most of which will have occupied their property for most of their lives, will be muscled out and replaced by new and wealthier occupants. For now, this process of gentrification appears to be a distant, yet still possible, scenario. The longterm social needs of communities, which also include housing, should not be overlooked in the quest for immediate economic returns. Conclusion It is clear that changes in Strait Street are occurring at a slow but steady rate, with one part of the street in particular being slowly revived as Valletta’s main nightlife spot. As a result, this research becomes important for a number of reasons. With findings 1 From 22,779 recorded in the 1931 national census, to 5,784 recorded in the 2011 national ‘Census of Population and Housing’ (National Statistics Office, 2012. suggesting that the regeneration of Strait Street is heading in a post-modern direction, the difficulty in finding a balancing act between the retention of a local identity and the need for competitiveness within the international scene becomes a major topic for discussion. Reading various media sources, it seems that the desire to regenerate Strait Street is so strong, that perhaps other considerations such as social inclusion and the retention of the local character and sense of place were not being considered, simply pushed aside, or worst, ignored. Care must however be given as to how such regeneration is carried out. With the help of different research methodologies used by the author, research points towards the importance of one of the most crucial themes within the social sustainability debate – the provision of decent and affordable housing. Given the progressive depopulation of Valletta in recent decades, and the number of vacant spaces, particularly in Strait Street, such aspect is vital to ensure the long term sustainability of any urban regeneration project. The upcoming European Capital of Culture event in 2018 should play a very important role in this regard. For Valletta, it is a unique opportunity to ensure the regeneration of some of its most deteriorated spaces. Meantime, this research will hopefully contribute to a lack of investigation on social sustainability and postmodern development with regards to the local context. The results obtained will be an addition to considerations about urban regeneration from such perspectives, shedding light on changes in urban lifestyles, which are occurring in different sequences, time periods and in places. This subject encompasses a wide range of issues and hence further research will need to be made by others, perhaps approaching the subject from new perspectives and also applying theories to the whole of Valletta. The research work disclosed in this publication is partially funded by the Master it! Scholarship Scheme. The scholarship is part-financed by the European Union – European Social Fund. References Bairner, A. (2006) Flaneur and the City: Reading the 'New' Belfast’s, Space and Polity, Vol. 10, No. 2, 121–134, 10(2), pp.121–134 Bramham, P. & Wagg, S. (2009) Sport, leisure and culture in the postmodern city, Farnham, England: Ashgate Pub. Chatterton, P. & Hollands, R. (2003) Producing Nightlife in the New Urban Entertainment Economy: Corporatization, Branding and Market Segmentation, International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 27(2), pp.361-85 Evans, G. (2003) Hard-Branding the Cultural City. From Prado to Prada. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 27, pp.417–440. Featherstone, M. (2007) Consumer Culture and Postmodernism (2nd Edition), Sage Publications Davidson, M. (2010) Social Sustainability and the City. Geography Compass, 4(7), pp.872–880 García, B. (2004) Cultural policy and urban regeneration in western European cities: Lessons from experience, prospects for the future. Local Economy, 19(4), pp.312–326 Glaeser, E.L. & Gyourko, J. (2005) Urban Decline and Durable Housing, Journal of Political Economy, vol. 113, no. 2 Grigsby et al. (1983) The Dynamics of Neighbourhood Change and Decline. Research Report Series, 4 Jacobs, J. (1961) The Death and Life of Great American Cities, New York: Vintage Books Edition Malta Environment and Planning Authority (2002) Grand Harbour Local Plan Malta Neal, P. (Ed) (2005) Urban Villages and the Making of Communities, Taylor and Francis Publishers Polèse, M. & Stren, R. (Eds) (2013) The Social Sustainability of Cities, Diversity, and the Management of Change, Toronto: University of Toronto Press Power, A. & Willmot, H. (2007) Social Capital within the Neighbourhood, London School of Economics and ESRC Research Centre for Analysis of Social Exclusion (CASE) Woodcraft, S. (2012) Social Sustainability and New Communities: Moving from Concept to Practice in the UK. Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences, 68, pp.29–42