The Impact of Corporate Sustainability on Organizational Processes and Performance Abstract

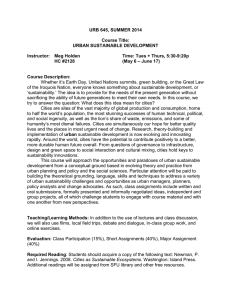

advertisement