Information Content and Dividend Policy of Publicly Listed Real Estate

advertisement

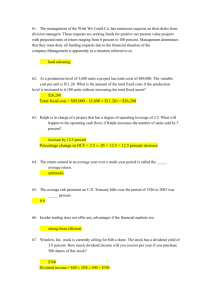

Information Content and Dividend Policy of Publicly Listed Real Estate Firms in Singapore SING, Tien Foo* Department of Real Estate National University of Singapore Date: 22 July 2004 Abstract: Publicly listed real estate firms offer an indirect form of real estate investment in Singapore, which are less restrictive in terms of dividend distribution and asset holding requirements compared to the REITs. Do the dividend policies of these real estate firms differ from those adopted by the US REITs as shown in the earlier findings by Wang, Erickson and Gau (1993) and Bradley, Capozza and Seguin (1998)? Our empirical results favor the agency costs hypothesis, which predicts a positive relationship between firms’ debt-to-asset ratio and dividend payouts. The agency costs effects were mainly differentiated by the dividend yields of real estate firms. Firm size was not a good proxy for cash flow volatility, and there were no significant signal in the dividend policy of firms with different market capitalization. The results rejected the dividend signaling hypothesis. However, the value-penalty hypothesis of Bradley, Capozza and Seguin (1998) that imposes downward corrections of stock prices for firms that fail to meet the divided target was not rejected. Firms with constant dividend payouts were also penalized with a 7.6% discount to the stock price compared to firms that distribute higher dividends than the previous years. Keywords: Signaling hypothesis, Agency Cost, Dividend Payouts *Corresponding Author. Email: rststf@nus.edu.sg. Address: Department of Real Estate, National University of Singapore, 4 Architecture Drive, Singapore 117566. The author wishes to thank LEE, Sze Teck for his research assistance. Errors, if any, remain the responsibility of the author. Comments are welcome. Information Content and Dividend Policy of Publicly Listed Real Estate Firms in Singapore 1. Introduction The regulatory requirement to distribute at least 90% of the net income as dividends is a unique feature distinguishing real estate investment trusts (REITs) from other forms of equity investment. This mandatory restriction is not strictly binding as many US REITs have been distributing more than twice the income as dividends (Wang, Erickson and Gau, 1993; Bradley, Capozza and Seguin, 1998).1 Does a high dividend payout matter to REIT investors? In the perfect world of Miller and Modigliani (1961) with no taxes and transaction costs, the dividend policy is irrelevant in determining the value of a firm. However, a change in dividend payout rate reflects important information concerning the management’s view of future earning prospect of the firm (Lintner, 19562; Modigliani and Miller, 1959). Miller and Modigliani (1961) further claim in the “information content of dividend” hypothesis that a change in dividend payout rate does matter, if the expected future earnings that cause the change in dividend payout rate is permanent in nature. The irrelevance of the high dividend payout ratio of REITs can also be explained using the dividend clientele hypothesis (Modigliani and Miller, 1961). Based on the hypothesis, we will expect the high dividend yield instrument to appeal to clienteles in the low income tax bracket group. Institutional investors with high income tax liability will be disadvantaged by the high dividend payouts of REITs. However, there is no empirical evidence thus far to verify whether the REIT clientele are composed of investors who prefer high dividend payouts. The dividend clientele effects, if exist, would not persist. When demand for the high dividend yield stock has been satisfied, the stock prices will be corrected at equilibrium. Further changes to the target dividend policy thereafter would have no significant impact on the firm’s share price. Would the dividend irrelevance hypothesis prevail for REITs, which are actively involved in trading real estate in a market characterized by imperfect information? Wang, Erickson and Gau (1993) found that REIT managers raise debt capital to fund a higher dividend payout policy, and subject themselves to the monitoring by the external capital market. Managers of REITs (agents) with access to free cash flows may be inclined to undertake sub-optimal investment projects that are not in the best interest of the investors (principals). Paying out a high ratio of dividend over income can be a good way to indirectly reduce the free cash flow agency problem. In a separate empirical test using 75 equity REITs over the 1985-1992 sample period, the results of Bradley, Capozza and Seguin (1998) study contradicted the earlier findings in the agency-cost hypothesis. They showed that REIT managers are more reluctant to pay high dividends when the debt level of REITs is high. The lower dividend payouts serve as a signal of future cash flow 1 2 Wang, Erickson and Gau (1993) showed that the dividend to income ratio is 1.65 based on 123 REITs selected in the study in 1988. Depreciation expense provides the main source of cash flows distributable back to REITs investors as dividends. Lintner (1956) found empirical evidence of 28 sample firms, which rely on current earning and its relationship with the existing dividend rate to determine the future change in dividends. Modigliani and Miller (1959), however, stress that it was the expected future earning, and not the current earning, that will affect the dividend payout rate of a firm. 1 volatility. The results were consistent with the information content of dividend hypothesis or the signaling hypothesis for REITs. The conflicting results of Wang, Erickson and Gau (1993) and Bradley, Capozza and Seguin (1998) with respects to the validity of the agency cost and the information signaling hypotheses may mean that the dividend puzzle remains unresolved in the REIT market, like in many other asset markets. Real estate market is a highly imperfect marketplace inherited with characteristics like fragmentation in transactions, illiquidity, high transaction costs, inefficient information, heterogeneous product type and high barrier of entry in some countries. Information asymmetric is inevitable between the manager (agent) and investors (principal) of REITs, which have more than 70% asset holdings in real estate. With the 90% mandatory distribution of REIT income, using retained earnings as internal capital will not be an option for REIT managers in real estate acquisitions. Although, Wang, Erickson and Gau (1993) and Bradley, Capozza and Seguin (1998) argue that the 90% dividend rule does not constraint how the managers could optimize their dividend policy either to instill more market discipline in monitoring the investment decisions, or to send signal of the cash flow volatility in the future.3 It does not, however, suggest that the resulting capital structure that relies heavily on external capital will be the most cost-effective and optimal for RETIs. Therefore, to eliminate the effects associated removing the “artificial” constraint on the dividend payout rate and other asset holding restrictions for REITs4, this study proposes to use all public firms listed in the real estate section of the Singapore Exchange to empirically test the firm-specific dividend policy in the real estate industry.5 This paper is organized into six sections. Section I gives the background and objectives of the study. The motivation of why the listed real estate stocks are selected for the empirical tests is also discussed. Since the dividend irrelevance proposition was conceptualized by Miller and Modigliani (1961), research on this topic has expanded profusely in financial literature.6 Therefore, the literature review intended in Section II will no way be exhaustive, but it makes sure that important and relevant papers will be selectively reviewed in the study to provide sufficient reference to the empirical findings. Section III discusses the dividend signaling and agency cost model and also specifies the empirical model for subsequent empirical tests. Section IV covers the empirical methodology, which includes data collection, sample statistics, and hypothesis testing methods. The empirical results are analyzed in Section V, and implications are drawn. Section VI concludes the findings with highlights of relevant implications for investors who hold substantial securitized real estate assets in the portfolio. 3 4 5 6 Lu (2002) showed in her study that REITs pay dividend in excess of the mandatory 90% requirement to reduce agency problem, and she, therefore, suggests that the regulatory provision is unnecessary for REITs. REITs are required to invest 75% of the equity capita in real estate related assets, and 75% of their income must be generated from rents from real estate and interests of real estate mortgages. In Singapore, there is also a restriction on REIT to undertake development activities, or to purchase vacant lands with development potential. Howe and Shen (1998) empirically tested the intra-industry information effects of dividend initiation announcements, and found that dividend initiation policy is firm-specific. This implies that our test of dividend policy of listed firms in real estate industry will not be biased. See Allen and Michaely (1995) for a comprehensive review of the dividend policy literature. 2 2. Literature Review Based on Miller and Modigliani (1961) irrelevance of dividend proposition, the firms’ decision on how their earnings should be divided between retained earnings and distribution as dividends back to investors does not matter in a perfect market. The dividend will not have any significant effects on the firm’s cost of capital, and the performance of the firm remains stable as long as the management’s decisions on financing and investment are not changed.7 The empirical results of Black and Scholes (1974) supported the dividend irrelevance proposition, and they found no significant effects of dividend policy changes will have on the firm stock prices. Modigliani and Miller (1959), however, suggest that dividend changes do convey information of the expected future earnings of firms, which is permanent.8 What information does the dividend changes convey? Battacharya (1979) John and Williams (1985), Miller and Rock (1985) develop theoretical signalling models that explain how firms’ current and future earnings can be signalled by dividend changes of firms under an asymmetric information framework.9 Signals of firms’ future cash flow volatility can also be conveyed by dividend changes of the firms (Eades, 1982; Rozeff, 1982; and Kale and Noe, 1990). There was no conclusion empirical evidence supporting the signalling effects of dividend changes. Fama and French (1988) showed that dividend yields explain only a small fraction of the short-horizon stock returns variations. Watts (1973) tested 310 firms in the US over the period 1945-1968 and found no compelling evidence that dividend changes convey significant information on the firms’ future earnings. In Kao and Wu’s (1994) generalized friction model, evidence of significant signalling effects of dividend changes on both expected and unexpected permanent earning change was observed after dividend stickiness was removed. The dividend signalling hypothesis was also supported by the empirical results of Brook, Charlton and Hendershott (1998), which showed direct link between cash flow shocks, dividend policy and stock returns. The signalling effects were not constant across firms. Lang and Litzenberger (1989) and Koch and Shenoy (1999) using Tobin’s Q ratio to differentiate the dividend signalling effects between under-investing and over-investing firms. Lang and Litzenberger (1989) found that stronger signalling effects of dividend in firms with over-investment (low-Q ratio). Koch and Shenoy (1999), however, showed that the relationships between signalling strength and the Tobin’s Q measure were well represented by a U-shape curve. Firms on both end of the investment scale (over-investment and under-investment) react more strongly to dividend information. The results were consistent with the free-cash flow agency hypothesis proposed by Jensen (1986), which suggests that firms will pay out more dividends to reduce the free-cash flows that are available for the managers’ 7 8 9 Cornell and Shapiro (1987) and Holder, Langrehr and Hexter (1998) found significant interaction between dividend and investment policies through empirical tests of the stakeholder hypothesis. Marsh and Merton (1987) found that the permanent earnings were better measured by stock price changes than accounting earnings. There were various signalling incurred, which include foregone funds for productive investments (Miller and Rock, 1985), transaction costs in issuing and retiring stocks (Battacharya, 1979; John and Williams, 1985), tax losses and liquidity demand by different clientele (John and Williams, 1985). 3 disposal. An alternative explanation for the high dividend payouts by low-Q firms was given by Easterbrook (1984) using the agency cost hypothesis. He observed that high growth firms pay out large dividends and raising new capitals simultaneously to support their investment activities. The firms’ dividend policies and external capital funding solve the agency problems by reducing the monitoring costs and risk aversion of managers. Wang, Erickson and Gau (1993) used the agency-cost hypothesis to predict the dividend policies and the determinants of the dividend payouts for REITs. Testing the dividend policy of 102 sample equity and mortgage REITs in the US over the period 1981-1988, they found significant evidence to support the agency cost hypothesis. Higher dividend paying firms are closely associated with firms with higher debt to asset ratios. The firms are subject to stricter monitoring by the external capital market. The trade-off for the lower agency costs in monitoring the managers’ behaviour is the corresponding higher floatation costs in external capital raisings (Rozeff, 1982; and Easterbrook, 1984). The negative relationship between dividend payout changes and asset growth rate found in this study was consistent with Rozeff’s (1982) agency cost argument, which suggests a direct link between dividend and investment policies. Different wealth effects of dividend payouts across equity REITs and mortgage REITs was another significant finding of Wang, Erickson and Gau (1993) study. Information of future cash flows of real estate in equity REITs portfolio is more unpredictable. Therefore, dividend payout changes for equity REITs convey more valuable information for investors, which was evidenced by higher dividend announcement wealth effects in equity REITs. In deciding the optimal dividend payout, Rozeff (1982) argues that firms evaluate the net benefits of lowering agency costs with possible increases in transaction costs in issuing external finance. His empirical results showed that firms’ dividend policies is inversely related to both firms’ past and future growth and systematic risks. The agency cost prediction by Rozeff (1982) on systematic risks was not inconsistent with the dividend signaling hypothesis (Eades, 1982; and Kale and Noe, 1990). Bradley, Capozza and Seguin (1998) use wealth-penalty for shareholders of firms experiencing cuts in dividend payouts as the signaling costs in explaining the dividend policy and cash flow volatility relationships. Their one-period wealth-penalty model predicts that managers of firms with volatile future cash flows pay lower dividends to avoid the possibility of having to cut dividends in the future. They empirically tested the information signaling effects of the model using three variables as proxies for cash flow volatilities: firm size, leverage and portfolio diversification. Using the dividend and firm data for a sample of 75 equity REITs over the period 1985-1992, they found that large firms with lower leverage are the ones with higher future cash flow uncertainties. These firms use lower dividend payouts as signal of the higher systematic and unsystematic risks of the firms. The negative relationship between dividend payouts and the debt to asset value (leverage measure) rejected the agency costs prediction found in earlier study by Wang, Erickson and Gau (1993). Using the dividend and financial data of non-REIT real estate firms listed in the UK between 1986 and 1998, Ooi (2001) re-affirmed the dividend signaling results of Bradley, Capozza and Seguin (1998). Dividend policy convey a positive signal of the future cash 4 flow volatility of real estate firms, and the results indirectly imply that information content of dividends is independent of the mandatory distribution constraint of dividend payout imposed on REITs. We extended the empirical tests of the dividend signaling and the Miler and Modigliani’s (1961) dividend irrelevance 10 hypotheses using listed Singapore real estate firms, which are not bounded by the statutory dividend distribution requirements. Compared to the UK real estate firms in Ooi’s (2001) sample, real estate firms in Singapore are not subject to capital gain tax in their dealings, and the dividend clientele effects with respects to different tax preferences are not critical in our model. Therefore, the results of our tests on the information content of dividends and the shareholders’ wealth can be interpreted purely in the signaling and information asymmetric framework. 3. Information Content of Dividends: Hypotheses and Empirical Specifications Testable hypotheses with respects to the irrelevance of dividends and information signalling of dividends will be empirically verified in this study using listed real estate firms in Singapore. Based on the basic empirical framework of Bradley, Capozza and Seguin (1998), two empirical models: value-penalty stock return model and dividend payouts model; are specified below for our empirical test purposes: 3.1. Value-Penalty Stock Return Model In dividend irrelevance hypothesis of Miler and Modigliani (1961), stock return is independent of dividend policy of firms, and there is no positive wealth effects associated with the announcement of dividend payouts. However, Bradley, Capozza and Seguin (1998) develop a one-period value-penalty model, which predicts that firms’ stock price will be inversely corrected, if firms declare cuts in dividend payouts. Discrete binary indicators are included into the stock return model to capture the cross-section variations of firms experiencing dividend cuts, and those practice stable “target payouts” policy. According Bradley, Capozza and Seguin (1998), it is the direction, and the magnitude of changes in dividend payouts that matters to investors. We propose the following stockprice model with discrete dividend cut indicator to test the irrelevance of dividends hypothesis: Ri,t = b10 + b11∆DYi,t + b12∆Di,t + b13(RIi) + b14(NCi) + ciXt + di + ui (1) where b10 is the overall constant in the model; bk is the common coefficient for the controlled variable; ci is the coefficient for the cross-sectional specific variable Xt; and, di and ui are the fixed cross-sectional specific effects and the error terms of the regression respectively. The dependent variable, Ri,t, is represented by the log-difference of the total return index of stock i, i.e [Ri,t = log(TIi,t) – log(TIi,t-1)], where TIi,t is the total return index of firm i, which captures both dividend and price gain from year t-1 to year t. The independent variables in equation (1) consist of (i) ∆DYi,t, which is the year-on-year change in 10 The dividend irrelevance hypothesis, which rejected any wealth effects associated with dividend policy announcements, was not tested in Ooi (2001) study. His empirical tests focus solely on the relationship between dividend payouts and the dividend determinants. 5 dividend yield variable; (ii) ∆Di,t, which measures the changes in dividend per share of firm i, i.e. [Di,t – Di,t-1]; (iii) RI is the binary dividend reduction variable, which has a value of 1 for firms experiencing a cut in dividend in year t compared the previous year, or 0 otherwise; (iv) NI is the no-change binary indicator that differentiate firms that adopt fixed and stable dividend policy with no–change in current year dividend payouts over the previous year with [NI = 1], vis-à-vis other firms with different divided policy year on year, [NI = 0]; and (v) Xt is the market specific variable, which is included in equation (1) to capture the cyclical fluctuation in the real estate market. The All-Property Share index return, which is the aggregate performance indicator of the property sector of the Singapore Exchange (SES), is used as proxy for this variable in equation (1). Based on equation (1), two hypotheses can be independently tested: (A) Miler and Modigliani’s (1961) dividend irrelevance hypothesis: H0(A): “In a perfect world with no tax, no transaction costs and no information asymmetry, there are no wealth effects accrued to shareholder with respects to changes in dividend policy. Dividend payouts are irrelevant to the stock price changes.” (B) Value-penalty hypothesis (Bradley, Capozza and Seguin, 1998): H0(B): “There is an economical significantly discrete penalty on share price of firms experiencing of cuts in dividend payouts. The decline in the stock value is dependent on the dividend reduction and not the magnitude of the cut.” H0(A) is not rejected, if the coefficient b11 in model (1) is not significantly different from zero, and dividend is thus irrelevance. The result implies that dividend changes of firms would not have any effects on the stock returns. Conditional on the dividend irrelevance results, we should then expect the stock return to be positively related to the earnings generated by the firms. If the null hypothesis is rejected, free-cash flow hypothesis and signaling hypothesis may be supported if the dividend changes are positively related to the stock returns, because managers of firms with excess cash flows will tend to distribute high dividend, so as to reduce agency problem relating to investment in suboptimal projects. The [b11 = 0] results could also use to explain the dividend clientele hypothesis, which suggests that investors are indifferent between receiving high dividend payouts over future capital gains, if they are not subject to differential tax rates. If clientele effects prevail and firms adjust their dividend policy to appeal to investors in the high income bracket, we would expect a negative relationship between dividend payouts and stock return. To further test the irrelevance of dividend effect, we use the discrete variable, NC, to differentiate firms adopting constant and stable dividend policy over other firms with either upward or downward adjustment to dividend payouts. We expect b14 to be statistically insignificant, if we expect that firm with no change in dividend policy to earn no abnormal returns over other firms. 6 The binary dividend reduction variable, RI, is included to test the wealth-penalty effects associated with reduction in dividend payouts by firms. We expect the coefficient b13 to be significantly negative, if the H0(B) hypothesis in Bradley, Capozza and Seguin (1998) value-penalty proposition is not to be rejected. The results then imply that the market does impose a fixed penalty or charge on the stock prices of a firm, when it declares a cut in dividend payouts. Positive empirical results in support of the value-penalty hypothesis were obtained by Bradley, Capozza and Seguin (1998) in their empirical tests using the US equity REITs. 3.2. Dividend Payouts Model The second model is a dividend payouts model, which is specified to test two seemingly contradictory 11 dividend payout hypotheses: agency cost hypothesis and dividend signalling hypothesis. The empirical dividend payout model is similar to that used by Bradley, Capozza and Seguin (1998), which consists of current and lagged period earnings, two measures of firm-specific uncertainty, and the market-wide control variable, which is written as follows: Di,t = b20 + b21 Yi,t-1 + b22 ∆Yi,t + b23 Ai,t + b24 Li,t + ci Xt + di + ui (2) The dependent variable, Di,t, is the dividends per share paid-out over the fiscal year t. Yi,t-1 is the lagged period earnings per share of firm i. ∆Yi,t is difference in ln-earnings per share of firms over the previous year, [Yi,t – Yi,t-1]. The two volatility variables are represented by A, which is the firm size variable measured by the market value of assets of firm i; and L, which is the leverage ratio computed as the total debt over the total asset value of firms. Following Bradley, Capozza and Seguin (1998) approach, we replace the two cash flow volatility variables, A and L, with a single fitted earnings variable, Zi,t, which is a linear combination of the firm asset value (A) and the leverage (L) variables. This is done in a two-stage process, where we first regress the dividend yield on the firm asset values and the leverage variable, and then substitute fitted value, Z i ,t , for A and L in equation (2) in the second stage process. Two opposing hypotheses relating to dividend payouts are tested using the regression model in equation (2): (C) Agency Costs Hypothesis (Rozeff, 1982; Easterbrook, 1984; Wang, Erickson and Gau, 1993; and others) H0(C): “In the absence of non-dividend monitoring mechanism in place, high dividend payouts are made by managers of firms, and simultaneously they raise capital from external market for new investments. The flotation costs incurred in new 11 The results of the earlier empirical studies on REITs in the US by Wang, Erickson and Gau (1993) and Bradley, Capozza and Seguin (1998) appear to be contradictory, and were inconclusive on whether the agency cost hypothesis or the signaling hypothesis prevails in explaining the dividend policy of firms. 7 capital raising exercise can be offset by the benefit of lower agency costs. The free cash flow can also be curbed to minimize overinvestment risks.” (D) Dividend Signaling Hypothesis (Eades, 1982; Kale and Noe, 1990; Bradley, Capozza and Seguin, 1998; and others) H0(D): “Dividend payouts are viewed as a signal of firms’ future cash flow volatility. Firms are penalized by market with a downward adjustment in their stock prices, when the firms reduce their dividend payouts. Therefore, when the expected future cash flows of firms are uncertain, the firm will adopt a more prudent dividend payout policy to avoid the value-penalty on their stocks.” The dividend signaling hypothesis of Lintner (1952) and Miler and Modigliani (1961) predict that dividend payouts carry the signal of current and future permanent earnings of firms. If the hypothesis is not rejected, we expect the coefficients b21 and b22 on earnings and earning changes to be significant and positive. On the signaling effects through the value-penalty hypothesis proposed by Bradley, Capozza and Seguin (1998), two variables were used to represent the cash flow uncertainty. The firm size is an inverse measure of cash flow uncertainty, which means that larger firms based on the asset values are more diversified in their cash flow sources, and thus the volatility of cash flows of these firms is also lower. There is, therefore, a positive relationship between the market asset values and the dividend payouts of firms, i.e. [b23 > 0]. Leverage or debt to asset value ratio is the second measure of cash flow, and it is an important variable in model (2), which will distinguish between the agency cost and the signaling hypotheses above. Firms with higher debt to asset value ratio are firms with higher cash flow volatility; and under the signaling hypothesis of Bradley, Capozza and Seguin (1998), these firms will likely to payout lower dividends in order to avoid market penalty on their share values, if they are not able to sustain the same level of dividend payouts, i.e. [b24 < 0]. If the coefficient b24 turns up to be significant, but positive in the sign, [b24 > 0], the agency costs hypothesis is not rejected, which implies that firms are more likely to pay out high dividend to increase external monitoring through debt capital market discipline. Firms may tend to raise debt from the market to fund new investments, and to meet the high dividend target set by managers. 4. Empirical Methodology 4.1. Data Sample The sample firms in our empirical tests are selected from firms listed under the “Property Section” of the Singapore Exchange (SES). Stock prices and financial data were obtained from the DataStream over a 12-year sampling period from 1992 to 2003. The sample periods cover one full property cycle in Singapore from the upward trend in the early 1990s to the boom in 1995 following by the bursting of the bubble in 1997 and the recovery from 2002. To ensure consistency in the sampling selection, the following criteria are adopted: 8 a) These firms must be listed in the property section of the Singapore Exchange (SES), and a substantial portion of the firms’ earnings are generated from property related businesses; b) Companies must have declared at least one dividend payout during the sample periods; c) Firms listed in foreign-currency denomination on SES and those with their main property business located outside Singapore were excluded; and d) Firms listed for less than 5 years were not considered because the relatively short financial data series. Based on the above criteria, three REITs, which come onto the SES market after 2002 were dropped from the sample list. Firms like Allgreen Properties Limited, Heeton Holdings Limited, HiapHoe Limited, HoBee Investment Limited, which were listed after 1999, were also excluded. Listed foreign-based property companies like Australand Holdings Limited, Cheung Kong (Holdings) Limited, AV Jennings Homes Limited and Hysan Development Company, whose business activities are distributed outside Singapore, were also dropped from the sample list. The final sample list includes 18 real estate firms listed on SES, which is shown in Table 1. The financial and price data of the firms over the 12-year sample period were collected, which consist of a total of 198 observations. Table 1: List of Sample Real Estate Firms No. Firm Code Company Name 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 * # SCOT BONV BKSE CPTL CHMI CITY CMHD GUOC HONG KPPL LCDV MARC MCLL OPHH SCGD SLND UOLD WING The Ascott Group Ltd Bonvests Holding Ltd# Bukit Sembawang Estates Ltd# Capitaland Ltd* Chemical Industries (Far East) Ltd.# City Developments Ltd China Merchants Holdings (Pacific) Ltd# Guocoland Ltd Hong Fok Corporation Ltd Keppel Land Ltd L C Developments Ltd Marco Polo Developments Ltd# MCL Land Ltd# Orchard Parade Holdings Ltd# SC Global Developments Ltd Singapore Land United Overseas Land Ltd Wing Tai Holdings Ltd Year of Listing on SES 1991 1973 1968 1989 1973 1963 1981 1978 1981 1973 1973 1981 1967 1968 1982 1963 Before 1989 1989 The now de-listed entity DBS Land was the predecessor of CapitaLand, prior to the merger of Pidemco Land and DBS Land to form the largest real estate company in the Asia in November 2000 . There were missing data for the total debt to total asset value data for some years in these firms, and could not be traced from the firms’ annual reports. 9 4.2. Descriptive Statistics - Dividend Policy of Sample Real Estate Firms On average, the 18 sample real estate firms pay out S$0.46 dividends per share, or an equivalent dividend yield of 2%, over the sample period 1992-2003. Bukit Sembawang Estate Limited paid out the higher divided per share of S$0.45 in 2003, and made the highest earning per share of S$1.38 in 1997. In term of dividend yield, Guocoland Limited recorded the highest yield of 15.65% in 1998. United Overseas Land (UOL) has the most generous dividend policy by distributing 65.39% of the net earnings back to investors as dividends. Figure 1 shows the historical time trends for the average dividend yields and average earnings per share of the sample real estate firms over the sample periods 1992-2003. The highest earning per share was recorded in 1997 at S$0.24 on average, and the highest average dividend yield of 4.86% in 1998, one year after the Asian’s financial crisis. The highest divided yield was attributed to the sharp decline in the average prices with at year-on-year change of -64.9% between 1997 and 1998. The 12-year descriptive statistics of the common pooled of 18 real estate sample firms were summarized in Table 2. The market values of the real estate firms were averaged at S$1.076 billion, and the largest capitalized firm was City Development Limited with a market value of S$10.933 billion. The performance of the real estate firms over the sample period was lacklustre registering a negative annual total return of 0.5%. The average values of the RI and NC indicators show that real estate firms in Singapore adopted a more conservative dividend policy with about 62.6% of the firms keeping their dividend policy constant over the sample periods. Only 14.6% of firms announced dividend cuts during the same periods. Table 2: Descriptive Statistics of Common Pooled Sample Symbol Mean Median Maximum Minimum Std. Dev. Skewness Kurtosis 4.4 Total Return Dividend Yield Dividends Per Share (S$) Earning Per Share (S$) TR -0.005 0.012 0.597 -0.764 0.213 -0.690 5.132 ∆D 0.020 0.015 0.157 0.000 0.020 2.562 15.264 D 0.046 0.030 0.450 0.000 0.061 3.246 17.784 Y 0.117 0.060 1.380 0.000 0.182 3.311 17.827 Total Debt to Total Asset Ratio L 0.346 0.353 0.681 0.000 0.152 -0.079 2.278 Market Value (S$ mil.) Dividend Reduction Indicator Dividend NoChange Indicator A 1076.489 469.710 10933.180 19.920 1629.545 3.022 14.065 RI 0.146 0.000 1.000 0.000 0.354 2.000 4.999 NC 0.626 1.000 1.000 0.000 0.485 -0.522 1.272 Regression Models Based on the stock return model and the dividend payouts model in equations (1) and (2), we will test various competing hypotheses on dividend policy, particularly the agencycost hypothesis and information signaling hypothesis. There are two widely used methods to structure the sample data sets, which consist of both cross-section firm related and time-series characteristics. The pooled data structure assumes the cross-sectional 10 properties of the firms to be constant and homogenous over times. On the other hand, the panel data structure is adopted if the cross-sectional firms’ differences are significant in affecting the variations in the explanatory relationships. Two set of regressions: pooled regression and panel regression will be estimated for our analyses. The fixed crosssection specific effects and the time-series fluctuations in the panel and pooled regression models are respectively controlled using a di vector and the all-property share returns, Xt. In the dividend payouts model (2), we would test the market value, Ai, and the total debt to total asset ratio, Li, as two proxies of cash flow uncertainties, and also use the fitted dividend yield variable, Z i ,t , as alternative cash flow volatility variable in the model. To further differentiate whether the clientele for high and/or low dividend yields will have effects on the relationships between firms’ dividend policy and leverage, we add an interactive variable, [DYi*Li], to the model (2). 5. Analysis of Results Two sets of regression using pooled data and panel data structures are run and the results are summarized in Tables 3 and 4. Table 3 summarizes the total stock return models as defined by equation (1), which is used to test the information signaling hypothesis by Miler and Modigliani (1961) and the value-penalty hypothesis by Bradley, Capozza and Seguin (1998). The tests of the agency cost hypothesis of Wang, Erickson and Gau (1993) and the signaling hypothesis of Bradley, Capozza and Seguin (1998) were reported in Table 4. 5.1. Is dividend policy relevant? Three out of the four models (except model 1d) show that b11 coefficients are positive and highly significant at 1% level, which reject the dividend irrelevance hypothesis, H0(A). Therefore, the results imply that dividend policy of real estate firms does convey valuable signal, and the effects of higher dividend payouts are positively adjusted in the share price of real estate firms. We may expect some form of dividend clientele effects in the market based on the negative relationship between the total return of stocks and the dividend yield changes, which are evidenced in all four coefficients, b12. In Singapore, investors are not subject to capital gain tax for their investments in stock market, they may therefore prefer to hold real estate stocks that have a more prudent dividend policy. Are firms’ stock prices be penalized by the market when the firms reported a drop in dividend payouts? The value-penalty hypothesis proposed by Bradley, Capozza and Seguin (1998) was confirmed in our models (1b) and (1c), with the stock value-penalty ranging from 3.88% to 19.38% at a 10% significance level. In the panel regression model (1d), the dividend no-change indicator was also found to be significant at 5% level, which suggests that firms with constant dividend payouts will also be penalized albeit at a smaller margin of 7.63%. The results in Table 3 indicate that the dividend policy is not irrelevant, and it is construed by the market as an important signal in the price adjustment process for the real estate stocks. 11 Table 3: Regression Results for Total Stock Return Models Pooled Regression Model Model (1a) Model (1b) Coefficient# Coefficient# Constant Change in dividend yield, ∆DYi,t Change in dividend per share, ∆Di,t Dividend reduction indicator, RIi Dividend no-change indicator, NCi Cross-section specific effects@ Adjusted R2 -3.2382*** (-5.9504) 0.8565*** (3.2207) Xt -3.6628*** (-6.2148) 0.7655*** (2.8398) -0.0388* (-1.8414) 0.0008 (0.9242) Xt 0.8243 0.8443 Panel Regression Model Model (1c) Model (1d) Coefficient# Coefficient# 0.0012 0.0784*** (0.1088) (2.846) -7.6121*** -8.4633*** (-14.2051) (-15.0309) 1.6175*** 0.6634 (4.0610) (1.4492) -0.1938*** (-3.9170) -0.0763** (-2.3619) Fixed Fixed 0.4903 0.5258 The total stock return, Ri,t , is used as the dependent variable for the models. # t-statistics are given in parentheses @ the cross-section property stock return specific coefficients for different firms were not reported. *** indicates 1% significance level ** indicates 5% significance level * indicates 10% significance level 5.2. Is dividend policy a signaling or an agency costs reduction mechanism? Table 4 shows that with the exception in Model (2e), the coefficients for the lagged earnings per share, b21, and the change in earnings per share, b22, are positive and significant in all four models at 5% level. In testing whether the dividend signaling or the agency cost hypotheses are relevant in explaining the dividend policy of the real estate firms, we will look at the two proxies for the cash flow volatility: firm size and leverage. According to Bradley, Capozza and Seguin (1998), the firm size variable is an inverse measure of a firm’s future cash flow volatility. Firms with larger and well diversified portfolio of assets are more protected against unsystematic risks, and the cash flows of these firms are also less volatile. These firms will pay out higher dividend compared to smaller and less diversified firms. Leverage, which is measured by the debt to asset ration in this study, will also give an indication of how risky is the future cash flow of the firms. Firms that are highly geared are more prone to future cash flow risk, and they are likely to pay out smaller dividend. Our results in the pooled regression models (2a and 2b) do not support the negative cash flow volatility and dividend payouts relationship proposed by Bradley, Capozza and Seguin (1998). The results in Table 4 show that firm size in our pooled regression models are negatively related to the dividend payouts. The findings were more consistent with the agency cost explanation, which suggests that firms with larger portfolio of assets may have less free-cash flows for distribution to investors as dividends. More capital will be required by these firms to support their growth strategies through new acquisitions. In Singapore, most of the real estate firms are heavily geared. It is more costly for these firms to raise external capital from the market vis-à-vis internal funding. Moreover, many 12 of the real estate firms in Singapore are family-controlled firms. These firms are more reluctant to subject the firms to external monitoring. Agency cost is thus higher in the local real estate firms. The coefficient for the debt to asset ratio variable, b24, was positive and significant in Model (2a). It was, however, inconsistent with the cash flow signaling hypothesis of Bradley, Capozza and Seguin (1998). The results supported the agency cost hypothesis of Wang, Erickson and Gau (1993), which imply that firms raise external capital to support for a high dividend payout policy, and thus subject the managers to external monitoring. We further tested whether the dividend-leverage relationships are subject to clientele effects of high dividend yield firms by adding an interactive variable into the Models (2b) and (2e). The results show that the coefficients for the interactive variables are positive and highly significant at 1% level. We expect that firms in higher dividend yield groups are likely to increase the firms’ debt-to-asset ratio as an effective mean of putting in place some forms of market monitoring on managers’ decision. After eliminating the higherdividend yield firms, we can then read the higher dividend payouts of firms as a signal of lower volatility in the future cash flow. The fitted dividend yield variable, which is a linear combination of debt-to-asset ratio and firm size variables, is used to represent the cash flow volatility of the firms in the dividend payouts models. The results again contradict the signaling hypothesis of Bradley, Capozza and Seguin (1998). Firms with higher fitted dividend yields may be associated with growth firms with a dynamic portfolio of real estate. These firms have to raise more external funds to support portfolio growth strategy and to maintain the dividend payouts at the same time. The firms with high free cash-flow may also fall into this category of high fitted dividend yield group. The agency cost hypothesis may suggest that managers of these firms will pay out large portion of the free cash-flows as dividend to reduce agency costs resulted by over-investment in sub-optimal assets. 6. Conclusion In Singapore, publicly listed real estate firms are a less restrictive vehicle compared to the REITs for indirect real estate investments, because these firms are not subject to the mandatory 90% dividend distribution requirement for their earnings.12 However, with no tax exemption granted at the corporate level, the listed real estate vehicle may not be the most efficient structure for holding real estate. Putting aside the debate on whether listed real estate firms or REITs are more efficient in the securitized real estate investment, this paper attempted to test whether dividend policies of the listed real estate firms in Singapore differ from the earlier findings of Wang, Erickson and Gau (1993) and Bradley, Capozza and Seguin (1998) using REITs in the US. 12 The listed real estate vehicle is also not subject to the asset holdings rule imposed on REITs , which requires REITs to have 70% of the income generated from real estate related assets. In Singapore, REITs are also prohibited from participating in read estate development activities, and their borrowing limit is capped at 35%. These are some of the restrictions that differentiate REITs from the listed real estate vehicles. 13 The empirical results on US REITs were thus far inconclusive. Wang, Erickson and Gau (1993) found than firms with higher debt-to-asset ratio are prone to agency problem. The managers of these firms tend to pay out more dividends and simultaneously go to the market to raise new capital, so that a more efficient and lower cost mechanism of monitoring by the market can be installed. The agency cost hypothesis was, however, rejected by Bradley, Capozza and Seguin (1998). They, instead, suggest that firms with higher debt-asset ratio have more volatile cash flows in the future, and these firms will have smaller dividend payouts to avoid being penalized by the market, when the dividend policy can not be sustained in the future. Do the managers of real estate firms in Singapore, which are not bounded by REITs rules relating to dividend distributions and asset holdings, use dividend policy to reduce agency costs in the firms? Our empirically results were more consistent with Wang, Erickson and Gau (1993), which predict a positive relationship between firms’ debt-toasset ratio and dividend payouts. The dividend signaling of future cash flow volatility of firms with higher leverage was not significant. The agency costs prediction was differentiated by firms with higher dividend yields. Firm size was also not a good proxy for cash flow volatility, and there were no significant signal by dividend policy of firms with different market capitalization. Our results showed that firms with larger asset portfolio tend to cut down dividend distributions, so as to retain more earnings for growth and expansion purposes (Rozeff, 1982). Our empirical results rejected the dividend irrelevance hypothesis of Miler and Modigliani (1961). A perfect world with no tax and not transaction costs does not fit the description of the indirect real estate market in Singapore. Dividend policy of the real estate firms does matter in determining the stock price performance of the real estate firms in Singapore. The value-penalty hypothesis of Bradley, Capozza and Seguin (1998) was also significant in explaining the negative relationship between dividend reduction and dividend payouts by the sample firms. Firms with constant dividend payouts were also penalized with a 7.6% discount to the stock price compared to firms that distribute higher dividends than the previous years. Reference: Allen, F. and Michaely, R. (1995), “Dividend Policy,” Handbooks in Operation Research and Management Science, Vol. 9, pp. 793-837. Bhattacharya, S. (1979), “Imperfect Information, Dividend Policy and “The Bird in the Hand Fallacy,” Bell Journal of Economics, Vol. 10, No. 1, pp. 259-270. Black, F. and Scholes, M. (1974), “The Effects of Dividend Yield and Dividend Policy on Common stock Prices and Returns,” Journal of Financial Economics, Vol. 1, pp. 122. Bradley, M., Capozza, D.R. and Seguin, P.J. (1998). Dividend Policy and Cash-Flow Uncertainty. Real Estate Economics, Vol. 26, No. 4, pp 555 – 580. 14 Brook, Y., Charlton, W.T. and Hendershott, R.J. (1998), “Do Firms Use Dividends to Signal Large Future Cash Flow Increase?” Financial Management, Vol. 27, No. 3, pp. 46-57. Cornell, B. and Shapiro, A.C. (1987), “Corporate Stakeholders and Corporate Finance,” Financial Management, (Spring), pp. 5-14. Eades, K.M. (1982), “Empirical Evidence on Dividends as a Signal of Firm Value,” Journal of Financial and Quantitative Analysis, Vol. 17, No. 4, pp. 471-500. Easterbrook, F.H. (1984), “Two Agency-Cost Explanations of Dividends,” the American Economic Review, Vol. 74, No. 4, pp. 650-659. Fama, E.F. and French, K.R. (1988), “Dividend Yields and Expected Stock Returns,” Journal of Financial Economics, Vol. 22, pp. 3-25. Holder, M.E., Langrehr, F.W. and Hexter, J.L. (1998), “Dividend Policy Determinants: An Investigation of the Influences of Stakeholder Theory,” Financial Management, Vol. 27, No. 3 (Autumn), pp. 73-82. Howe, J.S. and Shen, Y. (1998), “Information Associated with Dividend Initiations: Firm-Specific or Industry-Wide?” Financial Management, Vol. 27, No. 3, pp. 17-26. Jensen, M.C. (1986), “Agency Costs of Free Cash Flow, Corporate Finance, and Takeover,” the American Economic Review, Vol. 76, No. 2, pp. 323-329. John, K. and Willaims, J. (1985), “Dividends, Dilution, and Taxes: A Signalling Equilibrium,” the Journal of Finance, Vol. 15, No. 4, pp. 1053-1070. Kao, C. and Wu, C. (1994), “Tests of Dividend Signaling Using the Marsh-Merton Model: A Generalized Friction Approach,” the Journal of Business, Vol. 67, No. 1, pp. 45-68. Kale, J.R. and Noe, T.H. (1990), “Dividends, Uncertainty, and Underwriting Costs Under Asymmetric Information,” the Journal of Financial Research, Vol. 13, No. 4, pp. 265277. Koch, P.C. and Shenoy, C. (1999), “The Information Content of Dividend and Capital Structure Policies,” Financial Management, Vol. 28, No. 4, pp. 16-35. Lang, L.H.P. and Litzenberger, R.H. (1989), “Dividend Announcements: Cash Flow Signalling vs. Free Cash Floow Hypothesis?” Journal of Financial Economics, Vol. 24, pp. 181-191. 15 Lintner, J. (1956), “Distribution of Incomes of Corporations Among Dividends, Retained Earnings and Taxes, the American Economic Review, Vol. 46. No. 2, pp. 97-113. Lu, C. (2002), “Do REITs Pay Enough Dividends?” paper presented at the Asian Real Estate Conference, Seoul, Korea. Marsh, T.A. and Merton, R.C. (1987), “Dividend Behavior for the Aggregate Stock Market,” the Journal of Business, Vol. 60, No.1, pp. 1-40. Miller, M.H. and Modigliani, F. (1961). Dividend Policy, Growth and the Valuation of Shares. The Journal of Business, Vol. 34, No. 4, pp 411 – 433. Miller, M.H. and Rock, K. (1985), “Dividend Policy under Asymmetric Information,” the Journal of Finance, Vol. 15, No. 4, pp. 1031-1051. Modigliani, F. and Miller, M.H. (1959), “The Cost of Capital, Corporation Finance, and the Theory of Investment: Reply,” the American Economic Review, Vol. 29, No. 4, pp. 655-669. Ooi, J.T.L. (2001), “Dividend Payout Characteristics of U.K. Property Companies,” Journal of Real Estate Management, Vol. 7, No. 2, pp. 133-142. Rozeff, M.S. (1982), “Growth, Beta and Agency Costs as Determinants of Dividend Payout Ratio,” the Journal of Financial Research, Vol. 5, No. 3, pp. 249-259. Wang, K., Erickson, J. and Gau, G.W. (1993). Dividend Policies and Dividend Announcement Effects for Real Estate Investment Trusts. Journal of the American Real Estate and Urban Economics Association, Vol. 21, No. 2, pp 185 – 201. Watts, R. (1973), “The Information Content of Dividends,” the Journal of Business, vol. 46, No. 2, pp. 191-211. 16 Table 4: Regression Results for the Dividend Payout Model Pooled Regression Models Model (2a) Model 2(b) Model (2c) # # Coefficients Coefficients Coefficients# Constant Lagged period earnings per share, Yi,t-1 Change in earnings per share, ∆Yi,t Firm Size, Ai,t Debt to asset ratio, Li,t 0.3063*** (15.6534) 0.1373*** (6.1460) -4.87E-06** (-2.3885) 0.0384*** (3.6754) Interactive variable, DYi*Li Fitted dividend volatility, Z i ,t Cross-section specific effects@ Adjusted R2 0.2965*** (15.7076) 0.1421*** (6.6387) -3.44E-06* (-1.7345) -0.0012 (-0.0867) 1.7898*** (4.0116) 0.2731*** (16.1910) 0.1199*** (5.7101) 0.7897*** (5.2386) Xt Xt Xt 0.5301 0.5699 0.5631 Panel Regression Models Model 2(d) Model (2e) Model (2f) # # Coefficients Coefficients Coefficients# 0.0447*** 0.0468*** 0.0412*** (4.8652) (5.3939) (7.1734) 0.0474** 0.0278 0.0792*** (2.1389) (1.3024) (3.6332) 0.0335** 0.0350** 0.0511*** (2.1014) (2.3296) (2.9583) -1.30E-06 1.51E-06 (0.6516) (0.5440) -0.0070 -0.0433** (-0.3392) (-2.0499) 1.2983*** (4.6092) -0.2264 (-1.0136) Fixed Fixed Fixed 0.8286 0.8206 The dividend per share, Di,t , is used as the dependent variable for the models. # t-statistics are given in parentheses @ the cross-section property stock return specific coefficients for different firms were not reported. *** indicates 1% significance level ** indicates 5% significance level * indicates 10% significance level E-06 means the number is given in a multiple of 10-06. 17 Figure 1: Dividend Policy of Listed Real Estate Firms in Singapore (1992-2002) 0.40 5.00% 4.86% Average Earnings Per Share Average Dividend Yield 0.35 4.50% 3.50% 0.24 0.25 3.00% 2.60% 2.44% 0.20 2.50% 0.17 0.15 1.83% 0.15 0.13 0.11 0.10 0.05 0.00 0.09 1.51% 0.12 1.33% 1.59% 1.48% 1.42% 1.97% 0.13 1.73% 0.11 0.12 1.34% 0.07 2.00% 1.50% Average Dividend Yield (%) Average Earnings per Share (S$) 4.00% 0.30 1.00% 0.05 0.50% 0.00% 1992 1993 1994 1995 1996 1997 1998 1999 2000 2001 2002 2003 Year 18