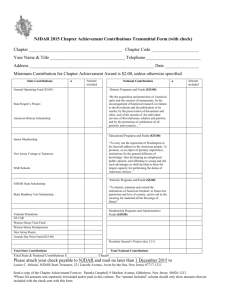

Bridges Building Between Academic Institutions, Business and

advertisement