Hiding behind Writing: Communication in the Offering Process of Mortgage-Backed Securities

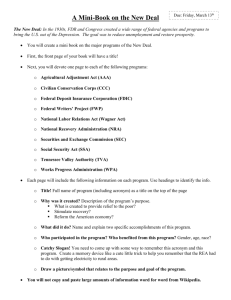

advertisement