Social Procurement and its Implications for Social Enterprise: A literature review

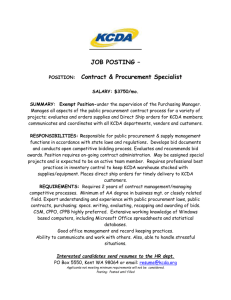

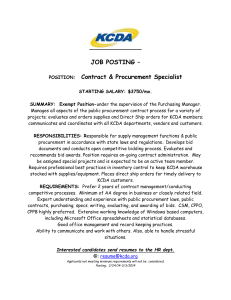

advertisement