The Domestic Impact of the Napoleonic Wars

advertisement

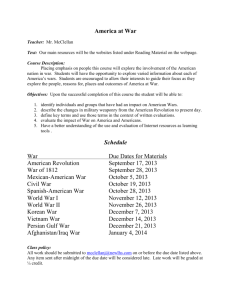

The Domestic Impact of the Napoleonic Wars Three Main Areas • Economic effects of wars • Impact on society • Political consequences The Economics of War (Elite) contemporaries often positive: • Ricardo: ‘Notwithstanding the immense expenditure of the government during the last twenty years there can be little doubt that the increased production on the part of the people has more than compensated for it.’ • Forbes (banker): ‘that wonderful extension of commerce and manufactures which, contrary to all former example, continued to swell as the war was protracted’ • Earl of Rosse: ‘never did this country, carry on a war in which it suffered so few privations’ Interpretations (Explorations in Economic History, 1987) attributes little to wartime dislocation or stimulus. • Emphasised the differences between Britain and the later industrialising economies of Europe arguing that British industrialisation occurred over a long period • Revolutionary change only occurred in a very few manufacturing industries • Thus war had little impact as British industrial growth occurred at such a slow pace Comparison of figures on Industrial Growth Industrial Output Crafts Deane & Cole 1700-60 0.7 1.0 1760-80 1.5 0.5 1780-1801 2.1 3.4 1801-31 3.0 4.4 1831-60 3.3 3.0 Percentage growth per year Crafts 0.7 0.7 1.3 2.0 2.5 GDP Deane and Cole 0.7 0.6 2.1 3.1 2.2 Interpretations (Journal of Economic History, 1984) in contrast attributes slow growth during industrial revolution to wars and their aftermath, on capital and labour markets especially. • Williamson asserted that modern economic growth follows a general pattern • It was only the stress of the wars that deflected Britain from this pattern. Wartime government borrowing crowded out productive investment. If it were not for the wars, industrial growth would have been more rapid following a normal pattern of early industrialisation. • But see (Journal of Economic History, 1990) who estimates there was not enough crowding out of investment to bear the weight Williamson puts on it and who find no evidence of crowding out (Journal of Economic History, 1987) Interpretations (Fernand Braudel Centre Review, 1989) eschews quantitative approach: data constraints and the need to consider short and long term consequences make examination of national accounts unsuitable. • Growth rates of domestic output declined between 1793 and 1819 • Consumption standards were 10-20% below the levels they may have attained if the economy continued to grow at pre-war rate. • But could one assume the growth rate of the 1780s would have continued indefinitely? Assessment Need to consider: • Changes in government revenue raising and expenditure on different industries. • Changes in agriculture • Pressure for innovation: technological, organisational and commercial. Revenue • 60% of extra funds raised by government to pursue war between 1793 and 1815 came from not borrowing • Tax strategy of government imposed major share of burden on consumption of population and encouraged private capital formation to continue. • Private consumption fell sharply from 83% of national expenditure in 1788-92 to 72% in 1793-1812 and as low as 64% in last years of war. • Household incomes were depressed by heavy taxes and by inflation. Redistributed income from wage earners to farmers, employers and property owners thus private capital investment remained stable. • Encouraged the stockmarket. Number of dealers rose during the war from 432 in 1792 to 726 in 1812 and the Stock Exchange was formed in 1802. The number of banks also increased. In London from 63-60 and in the country from 280-660. Estimates of total revenue from taxation 70 60 50 £m 40 30 20 10 0 1712 1722 1732 1742 1752 1762 1772 1782 1792 1802 1812 Structure of Central Government Tax Revenue Years Direct Customs Excise 1771-5 1791-5 1811-5 1831-5 1851-5 22.4 25.8 39.8 25.2 31.4 26.8 22.7 20.4 38.3 40.1 50.7 51.5 39.8 36.4 28.5 Total indirect 77.6 74.2 60.2 74.8 68.6 Nominal Wages, Prices and Real Wages (1778-82 = 100) Period Average fulltime earnings Cost of Living Index 100 Full employment real earnings 100 Real earnings adjusted for unemployment 100 1778-82 100 1783-87 100.2 99.1 101 101 1788-92 107.4 101.4 106 105 1793-7 129.6 119.2 109 105 1798-1802 154.6 153.8 103 99 1803-07 173.5 151.1 115 109 1808-12 188.7 181.8 104 98 1813-17 185.9 178.6 105 97 1818-22 166.5 150.9 111 102 1823-7 156.6 139.2 113 104 Agriculture & Industry • Wars had a commercialising effect on agriculture preventing the onset of diminishing returns. • Added to the incomes of landowners and farmers. The consolidation of land into larger farms was encouraged, as was the assertion of private rights to commons and wastes. • ‘the upswing in agricultural prices associated with the war years pulled those who owned and managed British agriculture into a cage from whence escape from the imperatives to invest, innovate and exploit farm labour became more difficult.’ (O’Brien) • Increases in customs and excise duties harmed only a handful of industries including building and construction, brewing and salt. • Iron, metal products, woollens, linens, candles, soap and leather experienced no significant additions to taxation on their inputs or outputs nor did they suffer from the rising costs of imported raw materials. Innovation • Rate and scale of bankruptcies in trading and industrial sectors peaked after the war. Particularly bad years were 1815-16 and 1819. • But losses were matched by the rise of new generations of entrepreneurs. Foreign commission agents settled in the provincial centres of industry and this was a direct consequence of the war. Wholesale warehouses which served only the export market were new developments. • In the aftermath of war, monetary policy designed to protect bondholders restrained the growth of trade and industry. It depressed the employment and incomes of the urban poor. But the low incomes and regressive taxation also raised the rate of saving and investment which was to the long term benefit of economic growth and income levels. • Short term costs of the wars need to be balanced against the capture of carrying trade, unification with Ireland, opening up of Latin America and seizure of enemy colonies. • In longer term wars inflicted much greater costs on the economies of rival European powers which gave Britain an advantage. Industrial Disputes • Trade unions flourished even during combination laws. • 1802 London shipwrights conducted a prolonged dispute & used intimidation to prevent strike breakers • ‘collective bargaining by riot’ also occurred in the woollen industry of the South West Luddism • Occurred on wide scale from 1811. • Began in stocking frame industry with proclamations bearing the signature Ned Ludd, King Ludd or General Ludd • Threatened to wreck machinery & occasionally threatened violence • Trades affected: framework knitting; woollen industry; & cotton industry • In 1779 failure of a Bill to regulate frameknitting industry had resulted in 300 frames being smashed The Leader of the Luddites, E Walker (1812) Nottingham • Frames were scattered round villages & easy to smash • March 1811-Feb 1812 smashed about a thousand machines at the cost of between £6,000 and £10,000. • 1811 Act was passed to secure the peace of Nottingham. • In March 1812, 7 Luddites were sentenced to transportation for life; • April 1812, Luddites attacked William Cartwright's mill at Rawfolds near Huddersfield. Event described by Charlotte Brönte in her novel Shirley. Interpretations (Luddism in Nottinghamshire) primarily industrial and futile attempt to halt the process of industrialisation? • Collective bargaining by riot? (Making of the English Working Class) sees it as quasi-political movement with ‘ulterior revolutionary objectives’. (The Labouring Classes) argues it was primarily industrial ‘a guerrilla campaign’ • Varied from region to region and industry to industry • Tapped into popular mood which was antigovernment and anti-employer. End of Luddism • Government feared revolutionary potential of Luddites. • Direct action continued to c. 1817 • 1816 was revival of violence following bad harvest & downturn in trade. • Troops used to end riots, 6 men were executed & 3 transported. • After the trials, Luddism subsided e but concurrently, 'Swing' riots erupted in the countryside William Cobbett, Political Register, 11 September 1819 Society ought not to exist, if not for the benefit of the whole. It is and must be against the law of nature, if it exists for the benefit of the few and for the misery of the many. I say, then, distinctly, that a society, in which the common labourer . . . cannot secure a sufficiency of food and raiment, is a society which ought not to exist; a society contrary to the law of nature; a society whose compact is dissolved. [Political Register, 11 September 1819] Society after the War • Heyday of aristocratic excess and swagger • Post-war economic boom for the landed • Passed Corn Law of 1815 which further secured landed incomes • Epitomised by Beau Brummell, Harriette Wilson and Lord Byron London Dandies or Monstrosities of 1816 (George Cruikshank) The Arrest A caution to the DANDIES taken from a late real scene The DANDY squinting through his glass Surveys the Ladies as they pass But still the Fribble lacks the wit To guard against the Bailiffs writ (J Le Petit, 1820) Harriette Wilson Blackmailer and lover of Lord Craven, Marquess of Lorne, Marquess of Hertford, Lord Brougham, Prince Regent and Marquess of Worcester Lord Byron, (Complete Poetical Works) 'Tis said Indifference marks the present time, Then hear the reason—though 'tis told in rhyme— A King who can't—a Prince of Wales who don't— Patriots who shan't, and Ministers who won't— What matters who are in or out of place The Mad—the Bad—the Useless—or the Base? Childe Harold’s Pilgrimage, J M W Turner, 1823. Lord Byron, The Age of Bronze Safe in their barns, these Sabine tillers sent Their brethren out to battle – why? For rent! Year after year they voted cent. Per cent., Blood, sweat and tear-wring millions – why? For rent! They roar’d, they dined, they drank, they swore they meant To die for England – why then live? – for rent! The peace has made one general malcontent Middle-class reactions • • • • • • • Response came particularly from the nonconformist sects and Evangelical Anglicans. The Society for the Promotion of Permanent and Universal Peace (known as the Peace Society) was formed in 1816 as a direct response to the Napoleonic wars. Alongside the urge to reform society and the religious motives against war were the secular influences of liberalism and humanitarianism which stemmed from the Enlightenment. Clapham Sect led by Henry Thornton, William Wilberforce, Charles Grant, James Stephen and Zachary Macaulay. Most of the inner core members lived at Clapham in South London where their close friend John Venn was the rector. Group published tracts, formed associations, and had an official periodical, the Christian Observer. Greatest public cause to which they devoted themselves was anti-slavery but were also crusaders for the renewal of Christianity, the sanctity of the family and female domesticity. Examples of these sentiments may be found in Mansfield Park by Jane Austen which was published in 1811. The same year, the Unitarian, Anna Laetitia Barbauld composed her darkly satirical poem Eighteen Hundred and Eleven Anna Laetitia Barbauld, Eighteen Hundred and Eleven But fairest flowers expand but to decay; The worm is in thy core, thy glories pass away; Arts, arms and wealth destroy the fruits they bring; Commerce, like beauty, knows no second spring Political Consequences • Reduction in prices and wages and the numbers of discharged soldiers and sailors added to unemployment. • December 1816: a political meeting at Spa Field ended in an armed attack on the Tower and the suspension of habeas corpus. • Government passed the so called "Gag Acts" in February and March 1817. • March 1817: the blanketeers from Manchester (blanket carrying weavers) assembled at St Peter’s Fields Manchester to march to London to present a petition to the Prince Regent. The magistrates read the Riot Act and sent in the army. • Later that year there was a riot of textile workers at Pentich in Derbyshire which ended in execution of Jeremiah Brandreth and two others and transportation of thirty more. Brandreth was encouraged by William Oliver the Home Office’s notorious agent provocateur. Print showing Henry ‘Orator’ Hunt speaking at Spa Fields Peterloo • Manchester Patriotic Union Society invited Henry ‘Orator’ Hunt and Richard Carlile to speak at public meeting on 16th August. Also included John Knight, Joseph Johnson & Mary Fildes, leader of the Manchester Female Reform Group • Magistrates were concerned at crowd ordered arrests of leaders. Yeomanry brought in to aid police & arrested speakers & newspaper reporters • In process, 11 people were killed & 400 wounded. Hustings Magistrates Aftermath • Richard Carlile managed to avoid being arrested & took first mail coach to London. • Placards began appearing in London with the words: 'Horrid Massacres at Manchester'. • Full report of the meeting appeared newspapers including the Times which used eye-witness accounts by moderate radicals including Archibald Prentice. "Down with 'em! Chop em down my brave boys: give them no quarter they want to take our Beef & Pudding from us! ---- & remember the more you kill the less poor rates you'll have to pay so go at it Lads show your courage & your Loyalty" ‘Dreadful Scene at Manchester’ Role of Women • Mobilised on huge scale: voted at meetings, formed associations with female officers, held their own meetings and presented addresses. • Women were claiming the right to public space and inclusion within the political nation. • Loyalist & government commentators rejected claim that women gave moral tone to protests instead presenting them as lax in manners & morals. Colour engraving by George Cruikshank, 1819 … but see also this caricature of female reformers by Cruikshank Consequences of Peterloo • Peterloo hardened political positions. • Government passed the Six Acts • Received enormous publicity and blunders were carried out in full view of the radical, active, provincial press. • Epstein has noted use of the ‘cap of liberty’; carrying branches of laurel & playing music such as Rule Britannia and God Save the King illustrate the change from Paineite republicanism to popular constitutionalism.