Document 13147893

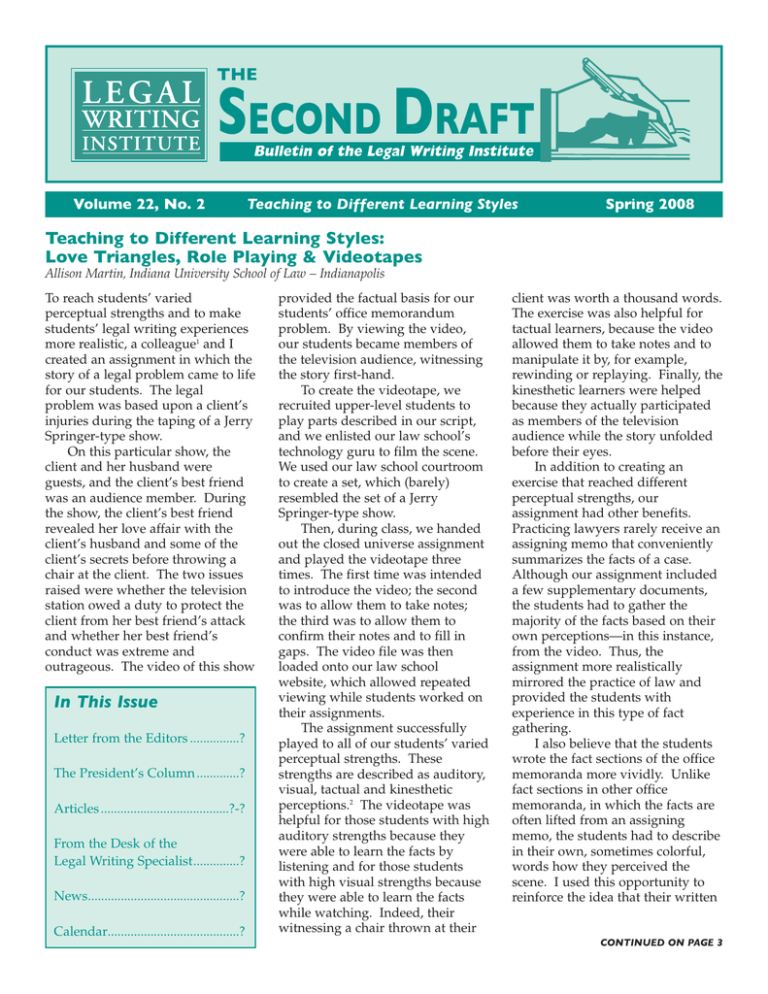

advertisement