Property and Oil and Gas Don't Mix: The Mangling

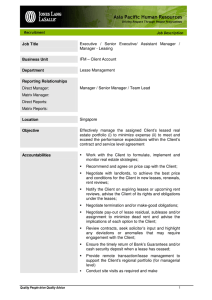

advertisement