EXECUTIVE ADVISORY OPINIONS AND THE PRACTICE OF

advertisement

EXECUTIVE ADVISORY OPINIONS AND THE PRACTICE OF

JUDICIAL DEFERENCE IN FOREIGN AFFAIRS CASES

WILLIAM

R. .CAsTO*

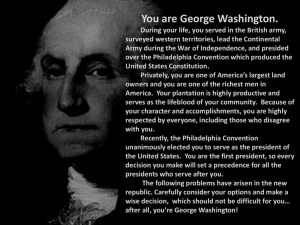

Because the legal constraints on executive action are not always

clear, U.S. presidents inevitably seek legal advice or advisory opinions regarding particular matters. During the first decade under

the U.S. Constitution, Supreme Court justices frequently provided

the president and the executive branch with independent legal

advice on a wide range of issues.' Nevertheless, in 1793 when President Washington sought advice from the justices regarding the

impact of the wars of the F'rench Revolution on D.S. neutrality, the

justices refused to give such advice? Their refusal has come to be

viewed as the origin of today's strict and well-established rule that

the federal courts may not provide the executive branch with advisory opinions. 3

Following the justices' refusal to advise him, the president

turned to his cabinet for advice; and so it is today. Presidents seeking legal advice look within the executive branch. This Essay examines a unique aspect of the attorney advisory function to the field

of foreign a'ffairs. As a practical matter, the restriction of the advisory function to the executive branch has resulted in a significant

expansion of presidential power under the Constitution.

Any attorney who has ever advised a client, in government or the

private sector, knows that advice is always ·given with an eye toward

the client's extralegal policy or business objectives. To be sure,

legal advice must rest upon plausible and reasonable legal analysis,

but there is frequently room for judgment. A good attorney or

adviser always exercises professional judgment-with appropriate

provisonniddisC:taiIfiersc:.-in favorof-tlre-cli-enc--Ih- practice this

* Allison Professor of Law, Texas Tech UniverSity School of Law. I would like to

thank Professor Bryan Camp and Dean Richard Rosen for their comments regarding this

Essay.

1. SeeWlu..rAM R CAsTO, THE SUPREME COURT IN THE EARLyRE;PUBLIG 97-98,147-57,

178-83 (1995) (discussing advisory opinions provided by early Supreme Court justices).

See generally

STEWART JAY, MOST HUMBLE SERVANTS: THE,ADVISORY ROLE OF EARLy JUDGES

(1997).

2.

3.

See CAsTO, supra note 1, at 75-82.

See, e.g., ERWIN CHEMERlNSKY, FEDERAL]URISDICTION § 2.2, at 49-50 (4th ed. 2003)

[hereinafter

CHEMERINSKY'S

FEDERAL JURISDICTION] •

501

502

The Geo. Wash. Int'l L. Rev.

[Vol. 37

sometimes results in a subtle shift from advising a client as to what

is legal to advising a client as to what is arguably legal.

There are several, and indeed powerful, reasons for. exercising

legal judgment to facilitate the achievement ofa client's extralegal

objectives. Mter all, an attorney is literally the client.'s agent and

thus has a fiduciary duty to assist the client. Even without regard to

this duty, advisers usually want tu assist their clients. Moreover, as a

matter of professional pride, an adviser finds great pleasl).re and

personal satisfaction in crafting legal analyses that willenable the

accomplishment of the client's goals. Of course, an adviser who

consistently facilitates the achievement of the client's goals can

------- -------expect-lo ret:"eive---substantial-monetary--and non-monetary rewards.

Similarly, a I"gal adviser who dOes not consistently exercise discretion to facilitate the client's goals will find his position as an adviser

in jeopardy. An attorney-adviser who is terminated or demoted

incurs obvious economic loss. Moreover, the attorney-adviser suffers non-economic losses, such as being deprived of the ability to

help the client as well as being branded a failure. These various

considerations can and do cause some legal advisers to give their

clients highly questionable advice:4

In theory, and usually in practice, an attorney's professionalism

safeguards against the provision of advice that rests upon highly

questionable legal analysis. Additionally, in the private practice of

law, a legal adviser is reluctant to advance extreme or highly questionable analyses because the advice is subject to independent

review by government regulatory agencies or by courts at the

behest of private individuals. Private legal advisers will routinely

exercise their judgment in favor of the client, but the possibility of

independent review Serves as a practical constraint upon the

adviser's judgment.

Government attorneys who advise the president and the exeCUtive branch face similar considerations as their colleagues in private practice. Government attorneys want to assist the people they

advise, and they have all the professional pride of their private SeCtor counterparts. Although the financial rewards are not as significant, non-monetary rewards such as prestige, promotion, and

especially assignment to important projects are very important to

government lawyers. A government attorney who does not consist4. See generally Richard W. Painter, The Moral Interdependence of Corporate Lawyers and

Their Clients, 67 S. CAL. L. REv. 507 (1994) (discussing how the relationship between corpOrate lawyers and thejr clients creates incentives for a lawyer to provide advice that violates

his or her moral principles to achieve the client's objectives).

~~-~------.,----.I

I

I

!

I

I

2000] Advisory Opinions and judicial Deference in Foreign Affairs Cases

503

ently facilitate the accomplishment of the government's policy

objectives will not attain these non-monetary rewards. 5

Although government attorney-advisers do not receive the enormous financial rewards that are available to some of their private

sector colleagues, government advisers may receive a form of nonmonetary compensation that frequently is unavailable in the private sector: personal satisfaction.' A presidential adviser usually is

personally committed to the achievement of the president's extralegal political objectives. The crafting of advisory opinions gives

the adviser both the professional satisfaction of a job well done and

the intense personal satisfaction 'of helping the president and the

nation to accomplish a political end that the adviser personally

believes is desirable. These various considerations lead government attorneys to shape their legal advice to facilitate extralegal

policy objectives. Respected commentators have noted that "[t]he

flavor of politics hangs about the opinions of the Attorney General."6 More recently a fonner associate White House counsel

frankly stated, "'We want to be aggressive. We want to take risks.'''7

Like their private sector colleagues, government attorney-advisers

are inclined to give advice based upon what they believe is arguably

legal.

A recently leaked Department ,of Justice (DOJ) memorandum

regarding a federal statute regulating torture exemplifies the practice of providing "arguably legal" advice. s In analyzing an act of

Congress outlawing torture, an assistant attorney general opined,

among other things, that Congress lacks constitutional power to

interfere "with the President's direction of such core war matters as

the detention and interrogation of enemy combatants."9 This

breathtaking claim of unilateral, unreviewable, and even dictatorial

presidential power is noteworthy for its studied refusal to consider

5. --For exarnple:-tiie-legaI'adViser to t:fie-Depirttnent 'o(Statewas'hirgely ex(:1tietea-----from the executive branch's creation of military tribunals to try alleged terrorists. A former Wh~te House offici~ explained ~at _'" [the adviser] was seen as ideologically squishy

and suspect .... People did not take him very seriously.'" Tim Golden, After Terror, a Secret

Rewriting of Military Law, N.Y; TIMES, Oct. 24, 2004, at A13 (quoting the White House

official) ,

6. PAUL M. BATOR ET AL., HART AND WECHSLER'S THE FEDERAL COURTS AND THE FEDERAL SYSTEM 71 (3d ed. 1988). See generally"NANoY v. l3~R, CONFLICTING LOYALTIES: LAw

AND POLITICS IN TIlE ATTORNEY GENERAL'S OFFICE, 1789-1990 (1992). '

7. Golden, supra note 5, at A12 (quoting the counsel).

8. Memorandum from Jay S. Bybee, Assistant Attorney General, to Alberto R. Gonzales, Counsel to the President (Aug. 1, 2002) [hereinafter DOJ Torture Memorandum],

http://news.findlaw.com/wp/docs/doj/bybee80102mem,pdf (last visited Oct. 9. 2004),

9. Id, at 31.

504

The Geo. Wash. Int'I L. Rev.

[Vol. 37

powerful arguments to the contrary. The president's adviser makes

no mention whatsoever of pertinent provisions of the Constitution lO and important Supreme Court decisions." Legal advice that

ignores powerful counter-arguments may be "arguably lawful" but

lacks credibility.

Part of the motivation behi~d the DOl's torture memorandum

seems self-evident. Presidential appointees have a personal, political commitment to the president's extralegal objectives. In this

case the president's advisers presumably sought to provide the

president the broadest possible discretion to win the war on terrorism. This is not to suggest or even hint that the attorney-adviser

_ _ _ .acted improperIr_0r in bad faith,-~The problem isfar--moresubtle

and therefore more intractable than bad faith. The president's

advisers simply exercised their discretion to assist their client and

to further the national interest as they saw it. Personal commitment like this makes the need for independent constraints upon

legal advice crucial. In practice, however, the independent constraints upon private-sector legal advice are atten1.1ated in the case

of the advisory function within the executive branch and especially

attenuated in the realm of foreign affairs. There is no government

regulatory agency charged with regulating foreign affai.rs, and, if

there were, the agency would report to the president. The entire

executive branch is subservient to the president in foreign affairs.

He is the boss.

Under the plan of the Constitution, the separation of governmental powers into independent branches of government can constrain presidential action, but the practice falls short of the theory.

A half century ago, Justice Jackson noted that the president "[b]y

his prestige as head of state and his influence upon public opinion

.. exerts a leverage upon those who are supposed to check and

10. See. e.g., U.S. CONST. art. I, § 8 (congressional power "[t]o make Rules for the

Government and Regulation of the land and naval Forces," "to'define and punish . ..

Offenses against the Law of Nations," and "to make all laws which shall be necessary and

proper for carrying into Execution ... all other Powers vested by this Constitution in the

Government of the United States").

11. See, for example, Little v. Barreme, 6 U.S. (1 Cranch) 170 (1804), in which a unanimous Supreme Court addressed the issue of congressional power to regulate the president's conduct of a congressionally authorized but undeclared war against France. The

Court, per Chief Justice Marshall, held that Congress could allow the president to seize

ships sailing to French ports but forbid the President to seize ships sailing from French

ports. Id.. at 177-78. This classic micro~management of a naval campaign is a clear example, of a congressional limitation upon, to use the memorandum's words, "the President's

direction of ... core war matters." DO] Torture Memorandum, supra note 8, at 31. Never~

theless, the Court held personally liable a Navy captain who was following the direct orders

of the Secretary of the Navy for violating the statute. See Little, 6 U.S. (1 Cranch) at 179.

..

i":::I0••:.....--------,-..2005] Advisory opinions and JUdicial Deference in F!Yreign Affairs Cases

505

balance his power which often cancels their effectiveness."'2 In

addition the institution of political. parties creates enormous friction within the legislative branch that significantly impedes efforts

to constrain presidential action. Again justice jackson noted,

"Party loyalties and interests, sometimes more binding than law,

extend [the president's] ... control into [Congress]."13 These loyalties and interests create a standing corps of presidential supporters in Congress that can be counted on to oppose efforts to curb

presidential actions. This enormous political friction is multiplied

by the Congress's bicameral organization, the Senate's extra-constitutional tradition of filibuster, and the presidential veto.

The subsequent history of the DOj torture memorandum illustrates a significant but less fonnal constraint upon the executive

branch. Someone eventually leaked the memorandum to the news

media, prompting the DO] to withdraw the opinion in response to

criticism. In its place the president's advisers substituted a more

measured analysis that eschewed the astonishing advice that Congress lacks authority to bar the president from torturing prisoners. 14 With a bit of lawyerly legerdemain, the new opinion

delphically explains: "Because the discussion in [the withdrawn

opinion] concerning the President's Commander-in-Chief power

and the potential defenses to liability was-and remains-unneCessary, 'it has been eliminated from the analySis that follows."'5 As

this episode demonstrates, public opinion can exert a powerful

constraint upon the advisory process. Nevertheless public opinion's influence is at best sporadic. If extreme but "arguably legal"

advice remains confidential oris leaked and approved by the public, the advisory process remains unbridled.

In theory the judicial branch also serVes as an iridependent constraint upon the· executive, but the practice doeS not approach the

12. y';Urtgstown Sheet &, Tube Co. v. Sawier, 343 U.S:. 579, 653-!f4 \1952fUackson.r,---concurring) .

13. ld. at 654.

14.

Memorandum from Daniel Levin, Acting Assistant Attorney General, to James B.

Corney, Deputy Attorney General (Dec. 30, 2004), http://www.usdoj.gov/olc/dag

memo.pdf (last visited Jan. 18,2005).

15. Id. at 2. This slight-of~hand language leaves intact the extreme advice that the

president's actions as commander-in-chief are beyond congressional control. The original

Torrnre Memorandum noted that the DO] had advised in at least four other formal opin-

ions that "Congress lacks authority under Article I to set the terms and conditions under

which the President may exercise his authority as Commander in Chief to control the

conduct of operations "during a war." DO] Tbrture Memorandum, supra note 8, at 34-35.

Because these opinions have not been withdrawn, the original torture memorandum's

extreme but "arguably legal" advice remains in effect.

506

The Geo. Wash. Iut'l L. Rev.

[Vol. 37

potential of the theory-especially in foreign affairs cases. In practice the courts tend to defer to the executive in matters of foreign

policy. The normative desirability of judicial deference is debatable, but the empirical reality of frequent deference is not. '6 Much

of this judicial deference is a function of a panoply of principles

and prudential considerations that, in many situations, effectively

disable the courts from addressing issues of law related to foreign

policy. In particular there is the fundamental constitutional provision that the judicial power of the United States extends only to

judicial cases and controversies.l7 Thus federal courts may not

render advisory opinions,'8 a plaintiff must have standing,19 and a

---"case must beripe2 °"but-must"not-be-mooto21 --These"corollaries are

not limited to disputes implicating foreign policy issues but are

often raised in that context. 22

In addition a bundle of considerations loosely labeled as the

political question doctrine frequently influences the courts to

subordinate their authority to the political branches. 23 In a leading case, the Court explained: "Not only does resolution of [foreign relations] issues frequently turn on standards that defy

judicial application, or involve the exercise of a discretion demonstrably committed to the executive or the legislature; out many

such questions uniquely demand single-voiced statement of the

Government's views."24 Finally the lower federal courts in the District of Columbia have relied upon their equitable discretion to

16.

See

MICHAEL

J.

313-25 (1990);

134-49 (1990).

GLENNON, CONSTITUTIONAL DIPLOMACY

HONGjU KOH, THE NATIONAL SECURIlY CONSTITUTION

HAROLD

17. U.S. CONST. art III, § 2.

18. See CHEMERINSKY'S FEDERALjURISDICTION, supra note 3, § 2',2, at 50.

19. See id. § 2.3; see also Coalition of Clergy, Lavvyers, & Professors v. Bush, 310 F.3d

1153, 1165 (9th Cir. 2002), eert. denied, 538 U.S. 1031 (2003) (fmding that the Coalition

lacks standing to challenge detention of persons held at Guantanamo Bay).

20. See CHEMERINSKY'S FEDERAL JURISDICTION, supra note 3, § 2.4; see also Dames &

Moore v. Regan, 453 U.S. 654, 688-90 (1981) (holding claim that suspension of private

claims pursuant to an Executive Agreement with Iran violates the Fifth Amendment of the

U.S. Constitution not ripe for review); Goldwater v. Carter, 444 U.S. 996,1000-02 (1979)

(Powell, J., concurring) (stating that a challenge by congressmen to presidential abrogation of a treaty with Taiwan was not ripe for review because Congress had not tal{en fonnal

action).

21. See CHEMERINSKY'S FEDERAL JURISDICTION, supra note 3, § 2.5.

22. For the operation of these corollaries in foreign affairs cases, see GLENNON, supr(l

note 16, at 315-25, and KOH, supra note 16, at 146-47.

23. See CHEMERINSKY'S FEDERAL JURISDICTION, supra note 3, § 2.6; see also GLENNON,

supra note 16, at 314,-21; KOH, supra note 16, at 146-48.

24. Baker v. Carr, 369 U.s. 186, 211 (1962).

2005] Advisory Opinions and Judicial Deference in Foreign Affairs Cases

507

deny remedies to members of Congress in foreign affairs and other

cases. 25

Judicial deference to the president in matters of foreign affairs

or national security is an empirical fact, but deference is not abdication. The Constitution provides scant guidance regarding the

extent of the president's foreign affairs powers, but the mantle of

foreign affairs cannot cloak all presidential actions. For example

there is a consensus that under the Constitution the president

lacks unilateral authority to start a war. Among the founders of the

Constitution, even the strongest advocates of presidential authority

agreed that only Congress is constitutionally empowered to "transfer the nation from a state of Peace to a state of War."26 Many of

the founders affirmatively took the same position, and there is no

record of even a single founder ever stating the president may lawfully start a war.27

Although the Constitution clearly vests Congress with the exclusive power to start a war, the small word, war, does not provide the

courts with very much guidance.. Do petty presidential adventures

in banana republics like Grenada, Panama, and Haiti constitute

"wars" forbidden by the Constitution, or are they merely dramatic

and bloody shows of force within the president's unilateral authority? Courts have been reluctant to answer these questions in the

abst!nce of supplemental guidance from Congress, and perhaps

the judges are right. If Congress lacks the will to protect its own

exclusive power in a close case, why should the courts intervene?

On the other hand, military action can be so clearly war-making

that the theoretically troubling .vagueness of the constitutional

standard becomes irrelevant. In the first Iraq War, a federal district judge signaled to the president that moving hundreds of

thousands of U.S. troops to the Middle East as part of a combined

25. Se'r,.g., Doman-'Il._UnitecLStates-Sec'yo£Def~851 F.2d 450,A51 (1).~ Cir.19Sll)_

(challenging legislation limiting support to Nicaraguan revolutionaries). The theory is that

members of Congress should not be allowed to bypass legislative procedures by seeking a

judicial remedy. See Carl McGowan, Congressmen in Court: The New Plaintiffs, 15 GA. L. REv.

241, 241-42 (1981).

26. Alexander Hamilton, Pacificus No.1 (June 29, 1793), in 15 THE PAPERS OF ALEXANDER HAMILTON 33, 42 (Harold C. Syrett ed., 1969); see also Letterfrom Alexander Hamilton

to James McHenry (May 17, 1798), in 21 THE PAPERS OF ALEXANDER HAMILToN 461, 461..,..62

(Harold C. Syrett ed., 1974); Alexander Hamilton, The Examination Number 1 (Dec. 17,

1801), in 25 THE PAPERS OF .A1.:ExANDER f-lAMILTON 444, 455-56 (Harold C. Syrett ed.,

1977).

27. For an exhaustive discussion, see Michael D. Ramsey, Textualism and War Powers,

69 U. CHI. L. REv. 1543 (2002); John C. Yoo, War and the Constitutional

69 U. CHI. L.

REv. 1639 (2002); and Michael D. Ramsey, T8)Ct and History in the War Powers Debate: A Reply

to Professur Yoo, 69 U. CHI. L. REv. 1685 (2002).

T,x,

508

The Geo. Wash. !rit'l L. Rev.

[Vol. 37

allied force of over a half million troops and launching an all-out

attack on one of the region's strongest military powers would

infringe on the Congress's exclusive war power. 28 The president

took the hint and sought congressional authorization for the war. 29

Except for extreme cases like the first Iraq War, the courts may

be right to stay clear of disputes regarding presidential authority

over foreign affairs. In the rough and tumble realm of politics, a

congressional reluctance to constrain the president may properly

be viewed as acquiescence. 30 The case for judicial deference, however, may not be as compelling when the constitutional issue shifts

from the president's extensive but vague foreign affairs powers to

- - - positive tonslltutiomullrohibitionsdesignedt<Fvruteet individuals.

Certainly most of th,e tactics of deference do not work in situations

where individual rights come into play. A criminal defendant's

defense during the course of a criminal prosecution cannot be dismissed as moot, not ripe, not supported by standing, a political

question, or involving remedial discretion. Nor are these avoidance techniques appropriate in the context of a petition for habeas

corpus. In these situations the courts must enforce the Constitution's guarantees of individual rights.

Of course, the courts' inclinatiOn to defer to the president may

reappear as a significant consideration in shaping the actual substantive scope of the individual protections under the Constitution.

For example, in the current war on terrorism, some judges are

inclined to defer to a presidential decision to incarcerate U.S. citizens indefinitely without tria!,31 Surely many of the Constitution's

protections do not extend to U.S. citizens engaged in combat operations against the United States in a foreign country,'2 but what of

U.S. citizens engaged in allegedly terrorist criminal activities within

the United States?33 Determining the scope of the Constitution's

protections in these cases is a difficult task. The critical prelimi28. Dellums v. Bush, 752 F. Supp. 1141, 1146 (D.D.C. 1990). But seeAugev. Bush, 752

F. Supp. 509, 512 (D.D.C. 1990) (finding that a court's equitahle discretion and the political question doctrine limit the ability of the judiciary to review the allocation of the war

power),

29. See Authorization for Use of Military Force Against Iraq Resolution,

FJ:.RJ. Res. 77,

102d Cong., Pub. L. No. 102-1, 105 Stat. 3 (1991).

30. See, e.g" Dames & Moore v. Regan, 453 U.s. 654, 678-82 (1981).

31. See, e.g., Padilla ex rei. Newman v. Bush, 233 F. Snpp. 2d 564, 593-99 (S.D.N.V.

2002), rev'd sub nom, on other grounds, Rumsfeld v. Padilla, 124 S. Ct. 2711 (2004).

32. See Hamdi v. Rumsfeld, 124 S, Ct. 2633, 2640 (2004),

33. See Rumsfeld v. Padilla, 124 S, Ct, 2711, 2715 (2004) (declining to reach the question of whether a U.S. citizen can be detained indefmitely without trial, but reversing the

lower court because the case was brought in an improper district court).

2005] Advisory Opinions and Judicial Deference in Foreign Affairs Cases

509

nary inquiry is which branch of government should make this

determination. If the courts defer to the executive, the substantive

scope of the Constitution's individual protections will be entrusted

to the president and his advisers.

It must be remembered that the practice of judicial deference

takes many subtle forms. In particular the practice typically is to

defer to presidential action !<lthet than to technical legal arguments advanced by the executive. For example in a case of torture

performed pursuant to the arguably legal advice in the DOl's torture memorandum, a court would not necessarily defer to the

breathtaking argument for exclusive presidential power. A court

might very well, however, defer to the underlying executive action

by finding some other, technical reason for refusing a remedy.3'

The net result would be a judicial refusal to restrain executive

action taken pursuant to an arguably legal analysis. Under these

circumstances the executive would continue to chart its course in

reliance upon unreviewed legal advice. In effect the practice of

deference lends an aura of authenticity to dubious claims of executive authority, and the president would continue to act on the

assumption that in matters related to war he is bound by neither

international law, nor treaties of the United States, nor even acts of

Congress.

In deciding whether to defer to a presidential decision in shaping the scope of constitutional protections, courts should consider

the fact that possibly unconstitutional governmental action is

almost never directed at members of society who, because of their

majority or socioeconomic status, pave a significant influence on

government. Therefore, neither Congress nor the president is

likely to champion their targets' legitimate interests. Deference to

the president in this context entrusts the scope of constitutional

rights to attorney-advisers of the president who probably craft their

opinions-with an-eye-to-whaHhey believe-is-arguably-constitutional

rather than what they believe is actually constitutional. Justice Jackson fully understood the distinction between a judge and an attorney-adviser. In the Steel Seizure Case, attorneys for the president

used a formal opinion written by Jackson when he was attorney

34. Different possibilities come readily to mind. A court might decide in the case of a

prisoner held incommunicado that the individuals guiding the lawsuit do not properly

represent the prisoner. See, e.g., Coalition of Clergy, Lawyers, & Professors v. Bush, 310

F.3d 1153, 1161-62 (9th Cir. 2002). The court perhaps wouid give a crabbed interpretation to an act of Congress in order to avoid having to 'decide a direct conflict betw'een the

Congress and the president. See, e.g.; Public Citizen v. United States Dep't ofJustice, 491

U.S. 440, 465-67 (19s9).

510

The Ceo. Wash. Int'j L. Rev.

[Vol. 37

general to support President Truman's later seizure of the steel

industry."' Jackson firmly rejected his opinion written a decade

earlier: "I do not regard it as a precedent for this, but even if I did,

I should not bind present judicial judgment by earlier partisan

advocacy."36 As Jackson undoubtedly understood, the practical

consequence of deference is to expand the president's actual

authority from what courts deem constitutional to what presidential advisers deem arguably constitutional.

--._--

•

35. Youngstown Sheet & Tube Co. v. Sawyer, 343 U.S. 579, 648-49 (1952) aaekson,].,

concurring) .

36. [d. at 649 n.17; see also BAKER, supra note 6, at 31-32 (1992).