Mobile Banking: The Answer for the Unbanked in America? Catherine Martin Christopher

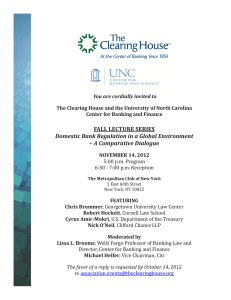

advertisement