SHAFFER NICASTRO B E

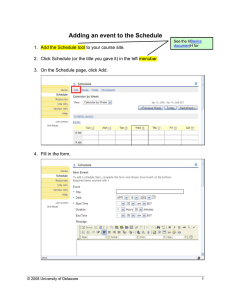

advertisement