Conditions on ellipsis licensing: evidence from gapping and cleft ellipsis* Matthew Reeve

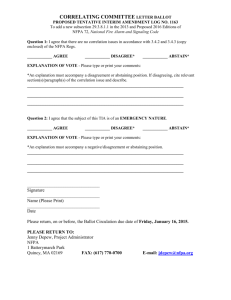

advertisement