Bruce M. Kramert CONVEYING MINERAL INTERESTS - MASTERING THE PROBLEM AREAS

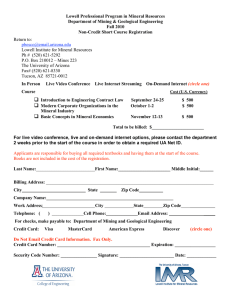

advertisement