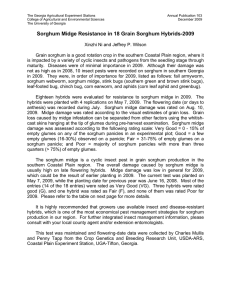

A multi-disciplinary (entomology, breeding, and agricultural economics) collaborative research... DEVELOPMENT OF BIOTIC STRESS-RESISTANT SORGHUM CULTIVARS FOR NIGER AND SENEGAL

advertisement