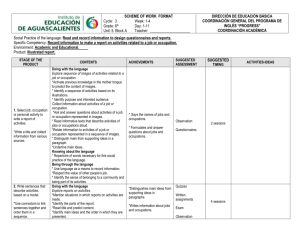

inf orms Information Systems Research

advertisement