Ethnic and Racial Disparities in Education: Disparities

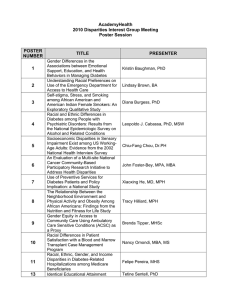

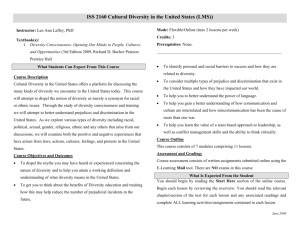

advertisement