DEVELOPING SAENS: DEVELOPMENT AND VALIDATION OF A STUDENT by

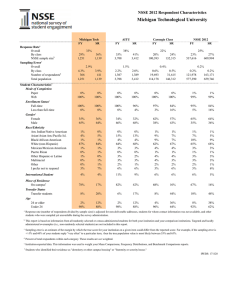

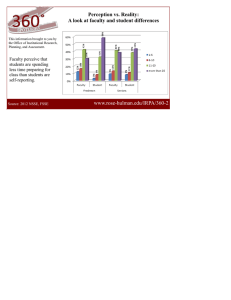

advertisement