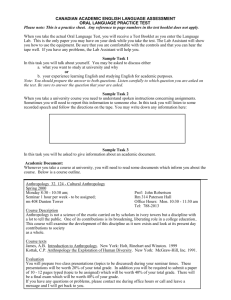

V S OICE

advertisement