GSR 2005 DISCUSSION PAPER

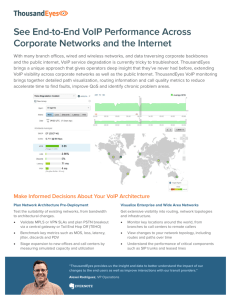

advertisement