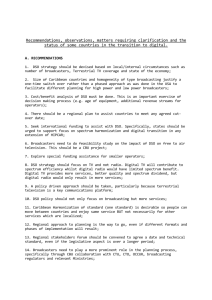

Practical Guide for diGital Switchover (dSo) in cameroon

advertisement