Incomplete cost-incomplete benefit analysis in transport appraisal Dr Robin Hickman

advertisement

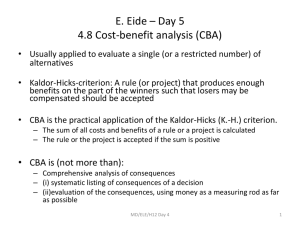

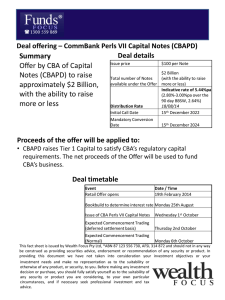

Institute for Climate Change and Sustainable Development, University of Malta Incomplete cost-incomplete benefit analysis in transport appraisal Dr Robin Hickman Bartlett School of Planning r.hickman@ucl.ac.uk Key Issues and Questions Transport appraisal involves making choices between different projects and budget allocations – deciding which projects might be the best spend of funding. The current appraisal approaches in transport infrastructure in the UK are based on WebTAG – primarily cost-benefit analysis (CBA), with a weak application of multi-criteria analysis (MCA). QUESTIONS: 1. Does this deliver the right projects? 2. Should we have a stronger critical debate on the appraisal approaches used in transport? Key Issues and Questions • • • • • CBA is important in the assessment of all projects – but has only a narrow remit – it is concerned with financial and ‘economic efficiency’ outcomes. In particular, it suffers from the problem of ‘quantifying the unquantifiable’ (Self, 1970; Adams, 1994; Ackerman and Heinzerling, 2004; Naess, 2006; Naess, 2016). Contemporary public policy problems cover wider issues of sustainability – but the definition is ‘fuzzy’ and open to multiple interpretations (Swyngedouw, 2007). WebTAG interprets sustainability, through the appraisal summary table (AST), as having three pillars (economic, social and environmental) – the economic pillar is given an implicit greater weighting – social and environmental objectives are poorly covered. Different interpretations of sustainability – as a ‘nested’ concept (Giddings et al., 2002), would mean that thresholds couldn’t be breached – this might lead to very different projects being developed? Two projects are examined – the South Fylde Line Electrification project and Heysham-A6 Link – the CBAs reveal the important components of decision-making – which are mainly time savings. We suggest participatory MCA might help the process – incorporating different actor views and assessing projects against local policy criteria – leading to a public policy debate facilitated by MCA? Does the UK appraisal system allow this quality of investment in urban LRT systems? BORDEAUX, FRANCE Is the transport project framed to achieve sustainability – is it assessed against the ‘correct’ success factors? Who does the assessment? Are some thresholds being breached, say the implications for the environment? Why are these not discussed? THAMES ESTUARY AIRPORT (LONDON) Tram-train systems are expensive – and are difficult to justify in the UK – but they bring the city-region together, allowing trips beyond the urban area, and peripheral areas to prosper. KASSEL, GERMANY In the UK, and many contexts, the ‘winners’ from transport investment are usually the larger urban areas and high income groups. Elsewhere, social goals are given much greater priority – the transport investment here is justified in terms of the regeneration of the former coal mining area. But the ‘economic efficiency’ of this project is very weak – it wouldn’t be funded in the UK. VALENCIENNES, FRANCE There are some examples in the UK – where the transport investment is used to support the regeneration of deprived areas. There is little demonstrable ‘benefit’ in the CBA – and the investment is justified against other policy goals. But there are very few of these. DROYLSDEN (MANCHESTER), UK The Practice of CBA CBA is seen, by its proponents, as providing: “Much of the information needed when making decisions about whether to approve an investment and how it might rank when compared with other transport schemes competing for limited funds.” (Worsley, 2014, p.17) “A framework within which impacts are quantified on a consistent basis, forcing decision makers to face up to numbers.” (Mackie et al., 2014, p.4). And, even, provides an example of “decision-making by democratic consent.” (Mackie et al., 2014, p.3). Key Problems with CBA in Transport Planning “Many of the judgements relative to the appraisal (and calculation of the likely impacts) of a transport infrastructure project can only be reasonably expressed and argued in fairly broad terms [...] they belong to the arena of public debate – and not to a world of endlessly hypothecated and quantified sums […] ultimately, they can only be taken through a series of policy judgements, which should be as open and explicit as possible, and supported by relevant information which by itself can never be conclusive. Greater rationality in the final decision is not helped, but hindered, by the use of notional monetary figures which either conceal relevant policy judgements or involve unrealistic and artificial degrees of precision. Those who suppose otherwise are heading for a peculiarly dreary version of 1984.” (Self, 1970, p.255, p.260) Why is the CBA process inaccessible to everyone but the economists involved: allowing the transport economists, transport planners and politicians to ‘hide their vested interests behind a supposed technical debate’? (Ackerman and Heinzerling, 2004). The Partiality of CBA (within the AST) All impacts • Business users and private sector providers • Commuting and other uses • Accidents • Physical activity • Journey quality • Noise • Air quality • Greenhouse gases Impacts that are quantified & monetised • Security • Access to services • Affordability • Severance • Reliability impact on business users • Regeneration • Wider impacts • Reliability impact on commuting and other users • Option and non-use values • Landscape • Townscape • Historic environment • Biodiversity • Water environment Impacts that it is not currently feasible to monetise Impacts that can be monetised but are not reported in the AST https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/we btag-tag-unit-a1-1-cost-benefit-analysis The Partiality of CBA (within the AST) All impacts • Business users and private sector providers • Commuting and other uses • Accidents • Physical activity • Journey quality • Noise • Air quality • Greenhouse gases Impacts that are quantified & monetised • Security • Access to services • Affordability • Severance • Reliability impact on business users • Regeneration • Wider impacts • Reliability impact on commuting and other users • Option and non-use values • Landscape • Townscape • Historic environment • Biodiversity • Water environment Impacts that it is not currently feasible to monetise • Estimation of benefits and costs of intervention – of the (partial) items that can be monetised – comparing a ‘with scheme’ and ‘without scheme’ case, over 60 years • Sometimes this is very partial Impacts that can be monetised but are not reported in the AST https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/we btag-tag-unit-a1-1-cost-benefit-analysis Incomplete cost v. incomplete benefit analysis All impacts • Business users and private sector providers • Commuting and other uses • Accidents • Physical activity • Journey quality • Noise • Air quality • Greenhouse gases Impacts that are quantified & monetised • Security • Access to services • Affordability • Severance • Reliability impact on business users • Regeneration • Wider impacts • Reliability impact on commuting and other users • Option and non-use values • Landscape • Townscape • Historic environment • Biodiversity • Water environment Impacts that it is not currently feasible to monetise • What if the issues not captured in the CBA are important? • Should impacts be traded off against each other? • Should thresholds be used? • Should different actor views matter – including political and public acceptability? Impacts that can be monetised but are not reported in the AST https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/we btag-tag-unit-a1-1-cost-benefit-analysis Case Studies Project 1: Tram Extension to Lytham Project 3: M6 Heysham Link Road Project 2: Tram-Train Preston-Blackpool Key Problems with CBA in Transport Planning Monetary Economic Value* Benefits Consumer User Benefits Project 1: Tram Extension to the South Fylde Line (to Lytham) (2010 prices and values) Project 2: Tram Train on the South Fylde Line (Preston to Blackpool) (2010 prices and values) Project 3(A): M6 Heysham Link Road (Fixed Demand) (2010 prices and values) Project 3(B):M6 Heysham Link Road (Variable Demand) (2010 prices and values) 399.4 209.5 625.5 237.3 Business User Benefits Indirect Tax Revenue Carbon Benefits Delays During Construction 216.4 10.4 3.4 - 51.8 6.4 2.1 - 1074.6 77.8 -14.6 -5.4 539.0 108.2 -20.8 -5.4 Accidents Benefits **Regeneration Benefits 12.9 111 6.6 132 111.9 - 55.4 - Present Value Benefits (PVB) 643.8 277.1 1869.9 913.9 301.7 154.0 301.1 382.0 65.9 381.6 157.9 5.1 163.2 157.9 5.1 163.2 342.7 -104.6 1706.7 750.7 Benefit to Cost Ratio (BCR) 2.1 0.7 11.5 5.6 Benefit to Cost Ratio (BCR) including regeneration benefit 2.5 1.1 - - Costs Investment Cost Operating Cost Present Value Costs (PVC) Net Present Value (NPV) The supposedly ‘technical’ and objective CBA is based on a range of assumptions that can be disputed and potentially framed in different ways: A. There are only a narrow selection of issues that go into the CBA – consumer users (commuting, shopping) and business users (travel during work) make up over 90% of benefits – other issues are marginal. B. Public transport investment cannot demonstrate the same time saving benefits as highways. •. The scale of benefit given to time savings C. subsumes all other impacts – e.g. the CO2 adverse impacts are less than 1% the size of the time savings gains (for the M6 Heysham Link) – and similar to delays during construction. D. There are no assumed operating costs for road projects (these fall on the driver – and are not included in the CBA), and indirect tax revenue is included as a benefit (the more cars, the better) – hence the system is heavily biased towards favouring road investment. E. The BCRs for the road projects are much higher, as more time savings can be demonstrated. BCRs for public transport projects are low – there are high investment and operating costs. Key Problems with CBA in Transport Planning There is a misplaced application of economic principles in public policy (infrastructure) appraisal – transport projects are too complex for CBA. Too much priority is given to the CBA result – and the application of MCA through WebTAG is too weak. Public policy goals include, but are much broader than, narrow financial criteria – there are also wide-ranging sustainability goals (with economic, social and environmental dimensions). Key problems: 1. Limits of quantification: there are many impacts that cannot effectively be monetised, and currently these are either poorly monetised or left out of the assessment – this leads to a very partial CBA (Ackerman & Heinzerling, 2004; Naess, 2006). 2. Use and application of travel time savings: why is saving time used as an important policy goal? Does aggregating a large number of small travel time savings help? The presumption that travel time savings are ‘realised’ and turned into productive time is strongly disputed (Metz, 2008). In particular, the concept of travel time savings does not transfer well to public transport journeys (Jain and Lyons, 2007), where at least some of the journey time is valued, and can even be productive. Key Problems with CBA in Transport Planning 3. 4. 5. Discounting: the practice of discounting doesn’t work for environmental or social issues, as long term problems are reduced in scale, and count for too little in the net present calculations (a £1 billion environmental cost in 50 years time = £146.8m in NPV). Distributional and equity issues: calculations are usually made net across a population; richer cohorts are favoured in the CBA through values of time; poorer cohorts may disproportionately receive the costs of noise, poor air quality; there is no consideration of the quality of development (gentrification), etc. – this is a major difficulty when social objectives, such as the need for regeneration or improve social equity, are important to a particular area. Limited ex-post (after the fact) validation: there is evidence to suggest that the numbers that go into the CBA are not accurate over time (Flyvbjerg et al., 2002) and that do-nothing projections are inaccurate (Nicolaisen and Naess, 2015). In the end, there is too little progress being made against important policy goals, such as the social and environmental dimensions of sustainability. An Alternative: Participatory MCA? Participatory multi-criteria assessment as an alternative (replacement or complementary?) approach (after Macharis, 2010): Masterplan-led (an integrated urban plan and transport plan) – to lead the transport projects and give strategic direction, and to give consistency with the planning approach. Process for participatory MCA? 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. Develop locally derived policy objectives and criteria, to match local policy requirements Weight criteria, to prioritise important local policy objectives Develop criteria indicators Assess impacts – incorporating different stakeholder views Use a decision-making conference (Leleur, 2012) to hold a public policy debate over different views on criteria, weighting and impacts http://www.vibat.org/participatory_mca/ user: UCL pw: MCA An Alternative: Participatory MCA? • • Multi actor workshops – comparison of results between groups and discussion on criteria and impacts Final decision takes into account multiple criteria impacts and views Conclusions www.sintropher.eu • Self (1970) labelled the practice of CBA in transport as ‘nonsense on stilts’ – and we can see many difficulties in contemporary appraisal. The CBA is often leading the decision-making – and there are huge problems as a result. • Similarly, in the EU Sintropher study there are difficulties in justifying funding for the ‘right’ projects – the appraisal system sifts out the wrong projects – in policy terms, and public transport investment proves very difficult to provide funding for. • CBA is still the primary approach to prioritising funding for transport investment projects – but it suffers from issues of quantification, use of time savings, discounting, distributional issues, and limited ex-post validation. • For some, it “perpetuates the deregulatory agenda under the cover of scientific objectivity” (Ackerman and Heinzerling, 2004) – it is biased towards funding road schemes. • A revised approach to decision-making on infrastructure projects is required – perhaps participatory and MCA-based – with a stronger emphasis on environmental and social sustainability issues – and a much stronger participatory dimension – used for public policy debate. You get what you measure, and perhaps we are measuring – and discussing it – in the wrong way?