Wider perspectives and more options for English Language and Linguistics students

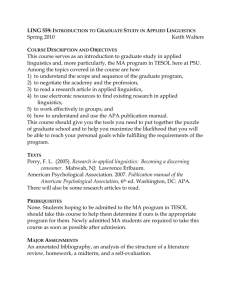

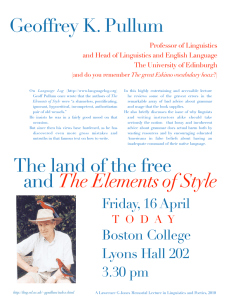

advertisement